Programme

Gazing into the Soul - Carl Theodor Dryer

When we talk about Carl Theodor Dreyer (1889- 1968), it’s easy to reference the soul-baring closeups of Renée Falconetti in The Passion of Joan of Arc or his stylistic evolution from the master of the close-ups to a minimalist filmmaker who fell in love with the long take. However, Dreyer also deserves to be remembered for his absolute devotion to three principles throughout his career: the power of the image, the power of spirituality (though not religion) and the power of human suffering.

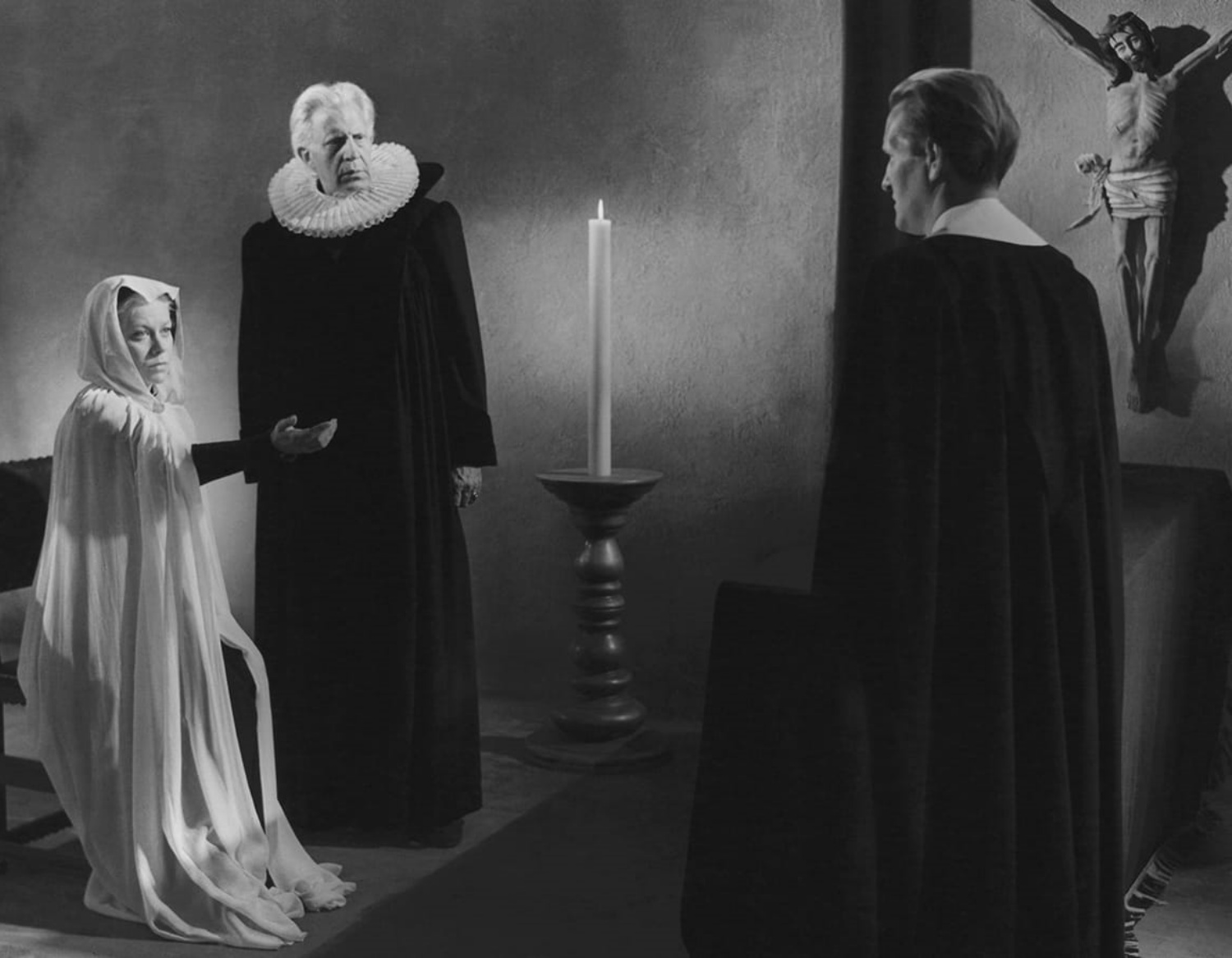

Dreyer’s conflicting relationship with spirituality and religion was most apparent in The Passion of Joan of Arc. In the depiction of her trial, the Danish maestro's lens quietly touches down on the French clergymen, who relentlessly interrogated the revered French martyr in an attempt to either discredit her claim of being on a mission from God or to shake her faith. While the film is reverent towards Joan’s commitment to her faith, it also depicts her persecutors – representing the system of organised religion – as oppressors standing on the wrong side of history.

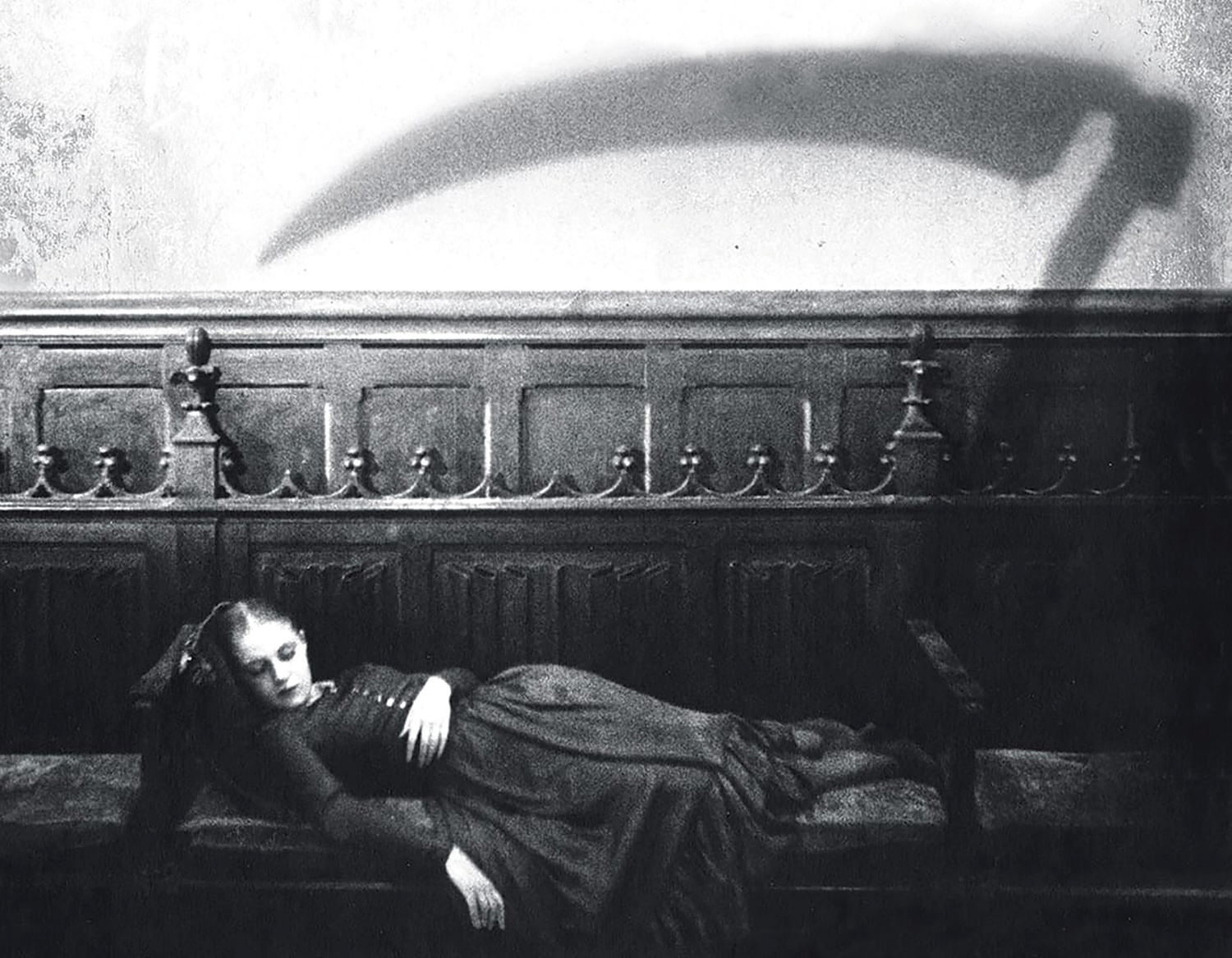

However, Dreyer was clearly more interested in capturing Joan’s suffering than the power of her spirituality, as evident in his perfectionist approach in capturing nuanced expressions using extreme closeups. Perhaps more so than a spiritualist, Dreyer was a humanist who was intrigued by both mankind’s suffering and its resilience in face of it. Many of his films – including Michael, Day of Wrath, Ordet and even Vampyr – saw characters suffering anguish and horror at the hands of oppressive figures of power. Yet for those who are persecuted, or maligned, Dreyer put them on the side of truth, empowering them with greater moral strength than their tormentors.

While Dreyer evolved into a more minimalist naturalist who employed long takes later in his career, he was mostly an expressionist who believed in using visuals to reflect his characters’ inner world. Even when Vampyr was supposed to be his transition into sound films, it was the film’s delirious visuals rather than dialogue that told the story. Dreyer knew that a single image or human expression will always say more about the human experience than all the words in the world. Through his aesthetic transformation, he caressed the human soul with love and faith, guarding it from the world of torment.