2025

The Existential Voyage of Wojciech Jerzy Has

At 19 St. Gertruda Street, Kraków, a plaque in honour of Wojciech Jerzy Has (1925-2000) sits at [...]

At 19 St. Gertruda Street, Kraków, a plaque in honour of Wojciech Jerzy Has (1925-2000) sits at his former home behind a glass window, almost obscured by sunlight refraction. For this singularly inventive yet silently rebellious Polish master filmmaker, it is perhaps the most fitting tribute.

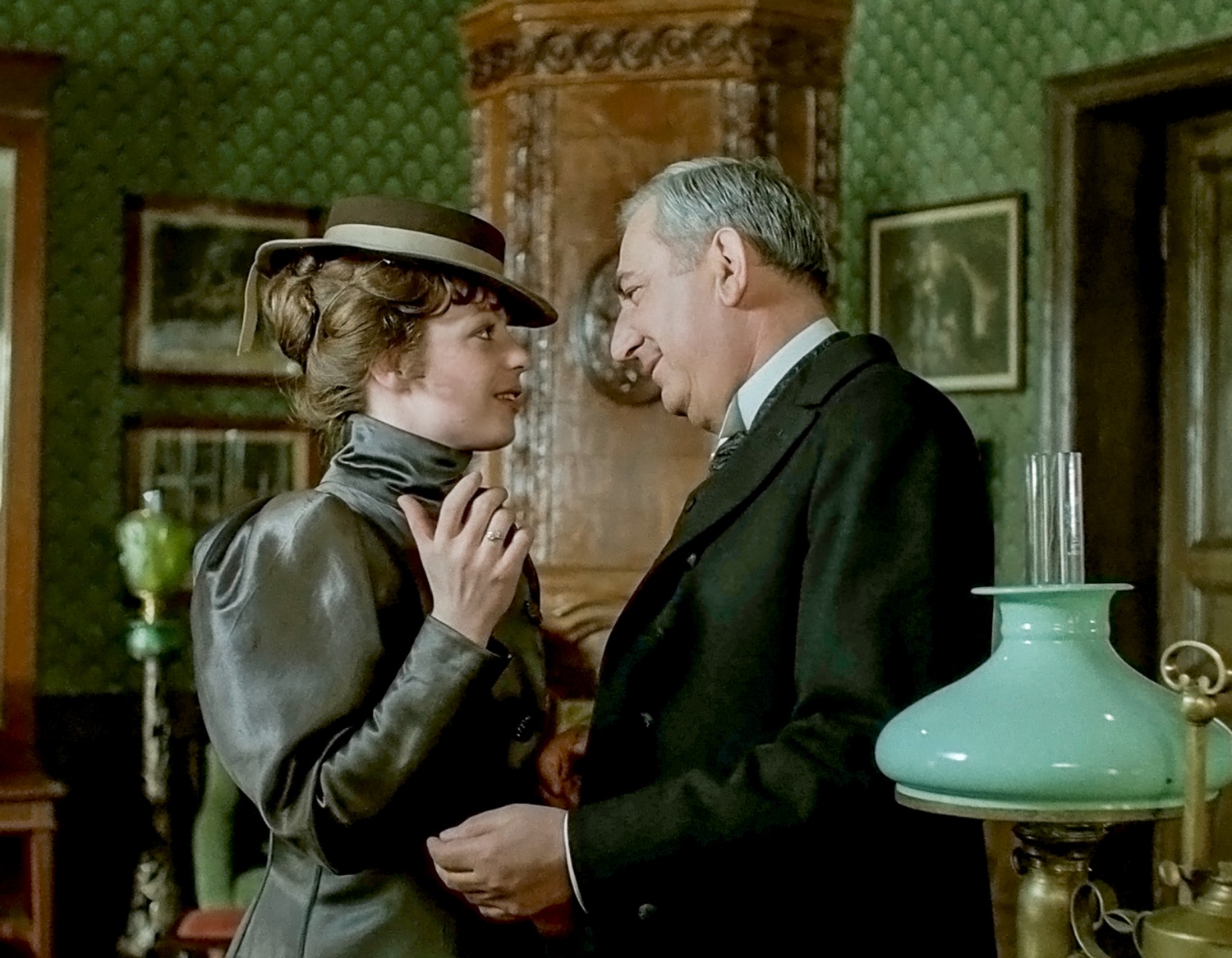

Windows are a recurrent motif in Has' films – an alcoholic gazing out at the street clock that tolls at his existential angst; and an elderly professor hiding behind curtains to lament life's futility. The divide between inner and outer worlds, the barrier between the tangible and the intangible, the duality of observing and being observed – all are revealed through a window. The window is still, yet time remains fluid; the subconscious invades reality, traversing freely across time and space. The past is overlaid onto the present, memory intertwines with dreams within the hourglass, oscillating back and forth as Has constructs the trajectory of his visionary cinema. Gliding through the labyrinth of time, his long takes and deep-focus lenses take us on the odyssey of his characters through physical and spiritual landscapes, peppered with bizarre imaginations, disorienting storylines, and fascinating dreams.

Emerging after World War II, Has stood apart from the prevailing Polish School of ‘the cinema of moral anxiety’. Distinct from Andrzej Wajda's historical scars, Jerzy Skolimowski's rebellious poetry, or Krzysztof Kieślowski's meditation on fate, Has was a prose poet of solitude and alienation, with a genius unnoticed in international cinema. Like a lone wolf, he had little interest in political strife or romantic heroism; his 14 feature films were mostly adaptations of Polish novels, set in the past to elude censorship. Never conforming to Socialist Realism during Stalinism, Has was closer in spirit to existentialism and the avant-garde, believing form is as important as content. Drawing inspirations as diverse as expressionsim, noir, surrealism, and the French New Wave, Has conceived an unparalleled cinematic universe, with his own sensibility and vision.

Though his talents remained largely unrecognised, Has’ works such as The Saragossa Manuscript and The Hourglass Sanatorium struck a deep chord with discerning admirers such as Martin Scorsese, Luis Buñuel, and the Grateful Dead's lead vocal Jerry Garcia, who contributed greatly to making his films known to the world. On the centenary of Has’ birth, revisiting his masterpieces reaffirms that true art transcends time.

Programme Partner

.png)

Gazing into the Soul - Carl Theodor Dryer

When we talk about Carl Theodor Dreyer (1889- 1968), it’s easy to reference the soul-baring closeups of [...]

When we talk about Carl Theodor Dreyer (1889- 1968), it’s easy to reference the soul-baring closeups of Renée Falconetti in The Passion of Joan of Arc or his stylistic evolution from the master of the close-ups to a minimalist filmmaker who fell in love with the long take. However, Dreyer also deserves to be remembered for his absolute devotion to three principles throughout his career: the power of the image, the power of spirituality (though not religion) and the power of human suffering.

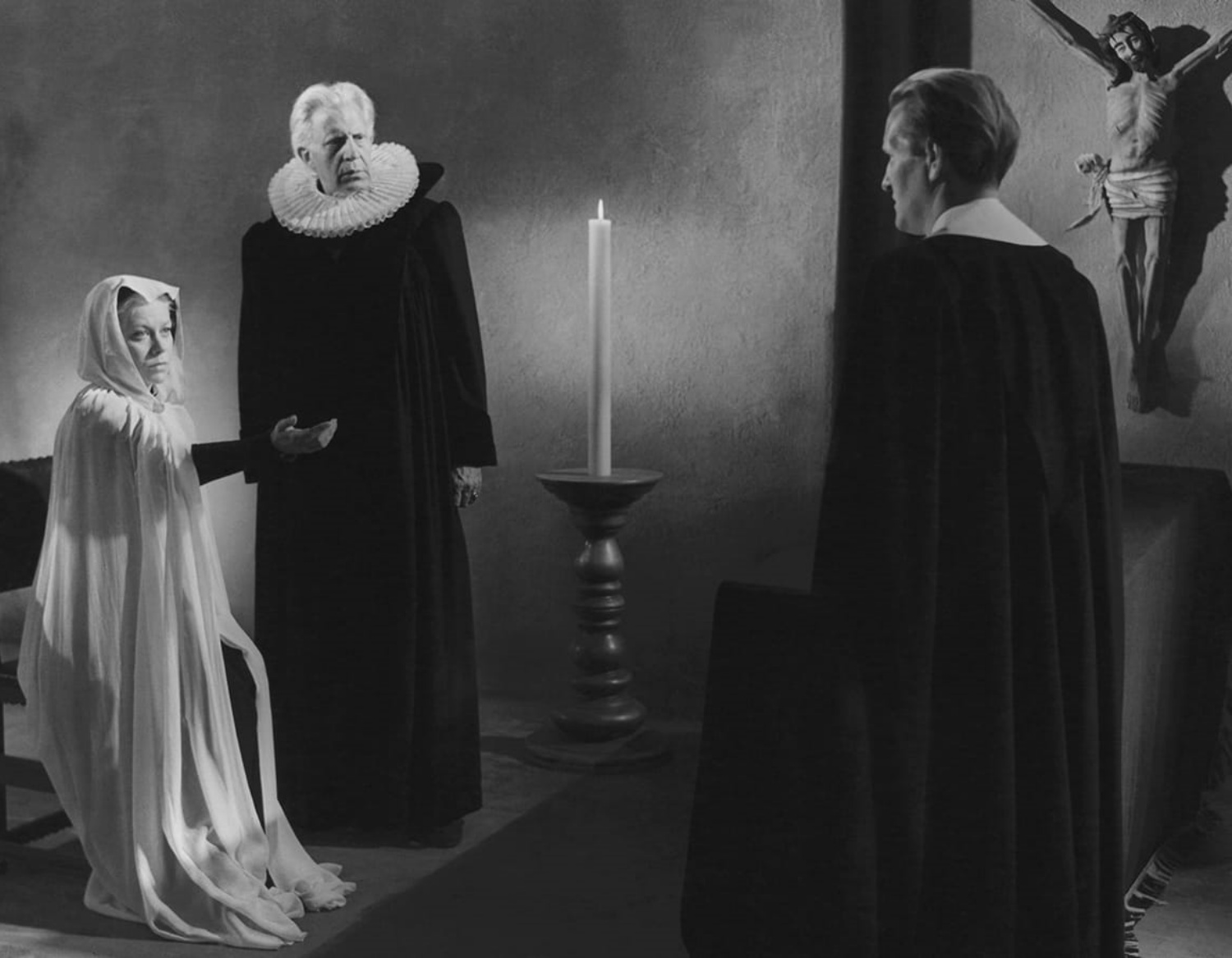

Dreyer’s conflicting relationship with spirituality and religion was most apparent in The Passion of Joan of Arc. In the depiction of her trial, the Danish maestro's lens quietly touches down on the French clergymen, who relentlessly interrogated the revered French martyr in an attempt to either discredit her claim of being on a mission from God or to shake her faith. While the film is reverent towards Joan’s commitment to her faith, it also depicts her persecutors – representing the system of organised religion – as oppressors standing on the wrong side of history.

However, Dreyer was clearly more interested in capturing Joan’s suffering than the power of her spirituality, as evident in his perfectionist approach in capturing nuanced expressions using extreme closeups. Perhaps more so than a spiritualist, Dreyer was a humanist who was intrigued by both mankind’s suffering and its resilience in face of it. Many of his films – including Michael, Day of Wrath, Ordet and even Vampyr – saw characters suffering anguish and horror at the hands of oppressive figures of power. Yet for those who are persecuted, or maligned, Dreyer put them on the side of truth, empowering them with greater moral strength than their tormentors.

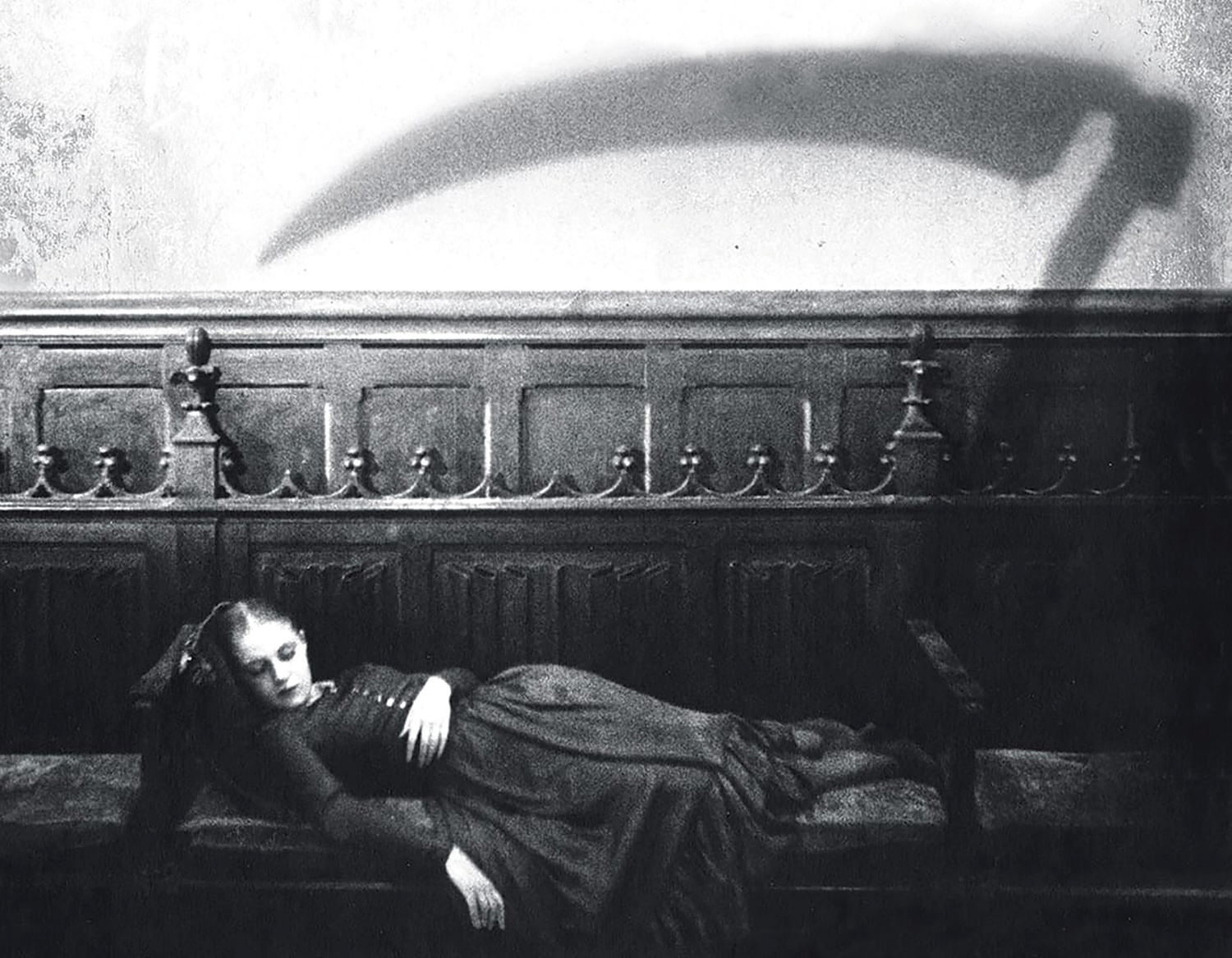

While Dreyer evolved into a more minimalist naturalist who employed long takes later in his career, he was mostly an expressionist who believed in using visuals to reflect his characters’ inner world. Even when Vampyr was supposed to be his transition into sound films, it was the film’s delirious visuals rather than dialogue that told the story. Dreyer knew that a single image or human expression will always say more about the human experience than all the words in the world. Through his aesthetic transformation, he caressed the human soul with love and faith, guarding it from the world of torment.