2017

Abbas Kiarostami Revisited II

By 2000, Abbas Kiarostami (1940-2016) had reached and surpassed highpoints for any global film career [...]

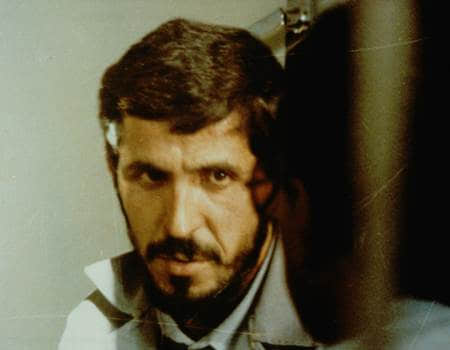

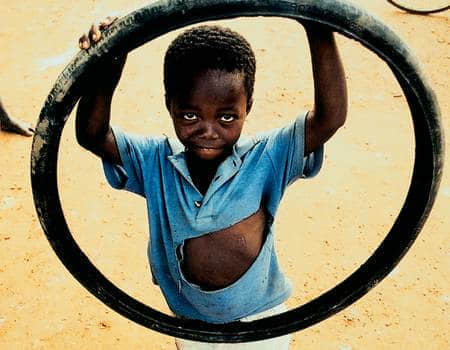

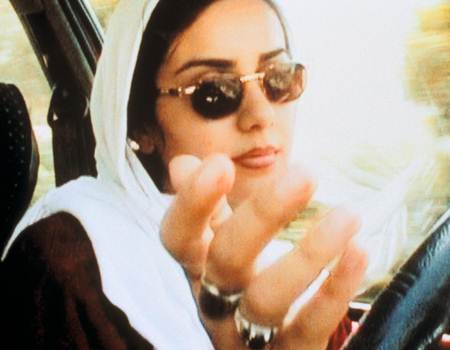

By 2000, Abbas Kiarostami (1940-2016) had reached and surpassed highpoints for any global film career – prizes in Cannes and Venice and the Akira Kurosawa Lifetime Achievement Award at the San Francisco International Film Festival (which he gave away) – amid critical adoration. His revered body of works explored the changing complexities of life in his native Iran, often through the eyes of children or alienated observers, while raising questions about the nature of film. But he was scarcely one to rest on such laurels, as these subsequent experiments with film remind us. In the next decade, Kiarostami probed the frontiers between “reality” and “representation” whether in his documentary about AIDS in Africa or in his reexaminations of life and landscapes in Iran. Meanwhile, he explored the very basics of what film can be and how it communicates among people.

The films of this period, with their stark and enigmatic names (numbers) take us along a journey that we can nonetheless link to early journeys to the heart of filmic realities, as his 1990 Close-up anticipates. Indeed, cars figure prominently, but they also evoke abstract geometries where dialogue inside a car may be more meaningful than events and people outside of it. At the same time, while these fragmented essays in film illuminate Kiarostami’s craft, they also provide reflective voyages through the course of the master’s career, revisiting places and peoples. And they question the very mechanisms and meaning of film in terms of elements so clearly dominated in the great director’s longer arc. Is dialogue necessary? Movement? Character? Can faces tell a story words do not?

Throughout his career, Kiarostami asked spectators to bring a great deal to his oeuvre and to learn from it. To see new worlds as he brought Iranian filmmaking and everyday life to world screens. To face the complexities of childhood or the social taboos of suicide. To ask about reality even as we were caught up in demanding narrations. And to learn what masterful film is and can be.

Alfred Hitchcock – The American Years : The Dangerous Lover

Decades after his death, Alfred Hitchcock (1899-1980) himself haunts us just as his iconic scenes [...]

Decades after his death, Alfred Hitchcock (1899-1980) himself haunts us just as his iconic scenes from Psycho (1960), or Vertigo (1958) or Rear Window (1954) linger in our imagination. Hitchcock fascinates both biographers and critics exploring the intertwined enigmas of the man and his work; he has even become the subject of two recent films trying to understand human relationships, imagination and art. Paradoxically, he remains among the most accessible of modern auteurs, whose films and television programmes remaincurrent, while proving enigmatic as man and artist.

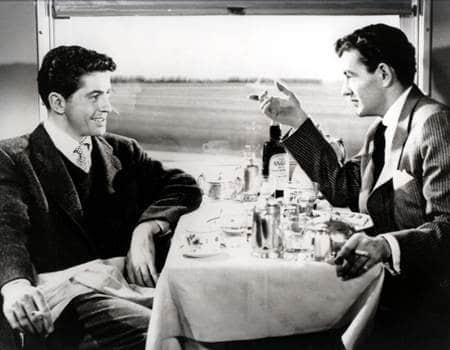

Born in 1899 in provincial England, Hitchcock became a writer before entering the emergent world of silent film. Despite stumbles, he scored his first chilling hit The Lodger(1926) and married his assistant director, Alma Reville, who became his lifelong collaborator. Through a decade of British successes, Hitchcock established his distinctive style – point-of-view shots, misleading and misled characters, punctilious control of details (and actors), emotional framing and his own elusive appearances in each film. In 1939, David O. Selznick lured him to Hollywood, where Hitchcock responded with Rebecca (1940). After some intriguing wartime films, his career reached new heights withSpellbound (1945) and Notorious (1946) and exploded in a cascade of unforgettable films in the 1950s and 1960s, from Strangers on a Train (1951) to The Birds (1963), amplified by a novel television series. Although Hitchcock remained visible thereafter as director and celebrity until his death in 1980, his later output never again equaled these triumphs.

Those who write about Hitchcock, the man, still grapple with him as both a tyrant of almost abusive power and a creative genius who probes and even heals our deepest fears. After generations of debate, these movies still speak for themselves as worlds of suspicion, danger, fear, love and superb mystery. No matter how many times we see them, we, too, dangle from a roof, face terror in a cornfield, repress our memories and primal fears. And think twice about our motels.

Suave, intense and so attractive. Yet, so complicated. The men are stylish, courageous and resourceful, but they also prove to be morally ambiguous and occasionally pure evil. And the women? Complex, beautiful heroines with so many pasts, so many lies, so much desire, whether icy blonde or innocent gamine. Love is never easy – or even safe – in Hitchcock’s worlds. Come, play along.

Alfred Hitchcock – The American Years : The Wrong Man

Decades after his death, Alfred Hitchcock (1899-1980) himself haunts us just as his iconic scenes [...]

Decades after his death, Alfred Hitchcock (1899-1980) himself haunts us just as his iconic scenes from Psycho (1960), or Vertigo (1958) or Rear Window (1954) linger in our imagination. Hitchcock fascinates both biographers and critics exploring the intertwined enigmas of the man and his work; he has even become the subject of two recent films trying to understand human relationships, imagination and art. Paradoxically, he remains among the most accessible of modern auteurs, whose films and television programmes remaincurrent, while proving enigmatic as man and artist.

Born in 1899 in provincial England, Hitchcock became a writer before entering the emergent world of silent film. Despite stumbles, he scored his first chilling hit The Lodger (1926) and married his assistant director, Alma Reville, who became his lifelong collaborator. Through a decade of British successes, Hitchcock established his distinctive style – point-of-view shots, misleading and misled characters, punctilious control of details (and actors), emotional framing and his own elusive appearances in each film. In 1939, David O. Selznick lured him to Hollywood, where Hitchcock responded with Rebecca (1940). After some intriguing wartime films, his career reached new heights with Spellbound (1945) and Notorious (1946) and exploded in a cascade of unforgettable films in the 1950s and 1960s, from Strangers on a Train (1951) to The Birds (1963), amplified by a novel television series. Although Hitchcock remained visible thereafter as director and celebrity until his death in 1980, his later output never again equaled these triumphs.

Those who write about Hitchcock, the man, still grapple with him as both a tyrant of almost abusive power and a creative genius who probes and even heals our deepest fears. After generations of debate, these movies still speak for themselves as worlds of suspicion, danger, fear, love and superb mystery. No matter how many times we see them, we, too, dangle from a roof, face terror in a cornfield, repress our memories and primal fears. And think twice about our motels.

Pity the Hitchcock hero. Dapper and wellspoken, of course. Innocent, mainly. But also misled. Mistaken. Chased. Targeted. Never quite sure of who to trust, whether colleagues or the astonishing woman who interrupts his life and turns it upside down. A woman he wants to save but who, so often, ends up saving him, as we watch, breathless and beguiled ourselves.

Alfred Hitchcock – The American Years : Pure Cinema

Decades after his death, Alfred Hitchcock (1899-1980) himself haunts us just as his iconic scenes [...]

Decades after his death, Alfred Hitchcock (1899-1980) himself haunts us just as his iconic scenes from Psycho (1960), or Vertigo (1958) or Rear Window (1954) linger in our imagination. Hitchcock fascinates both biographers and critics exploring the intertwined enigmas of the man and his work; he has even become the subject of two recent films trying to understand human relationships, imagination and art. Paradoxically, he remains among the most accessible of modern auteurs, whose films and television programmes remaincurrent, while proving enigmatic as man and artist.

Born in 1899 in provincial England, Hitchcock became a writer before entering the emergent world of silent film. Despite stumbles, he scored his first chilling hit The Lodger (1926) and married his assistant director, Alma Reville, who became his lifelong collaborator. Through a decade of British successes, Hitchcock established his distinctive style – point-of-view shots, misleading and misled characters, punctilious control of details (and actors), emotional framing and his own elusive appearances in each film. In 1939, David O. Selznick lured him to Hollywood, where Hitchcock responded with Rebecca (1940). After some intriguing wartime films, his career reached new heights with Spellbound (1945) and Notorious (1946) and exploded in a cascade of unforgettable films in the 1950s and 1960s, from Strangers on a Train (1951) to The Birds (1963), amplified by a novel television series. Although Hitchcock remained visible thereafter as director and celebrity until his death in 1980, his later output never again equaled these triumphs.

Those who write about Hitchcock, the man, still grapple with him as both a tyrant of almost abusive power and a creative genius who probes and even heals our deepest fears. After generations of debate, these movies still speak for themselves as worlds of suspicion, danger, fear, love and superb mystery. No matter how many times we see them, we, too, dangle from a roof, face terror in a cornfield, repress our memories and primal fears. And think twice about our motels.

Some works that stand out even in a gallery of masterpieces. For moments that shock us, even when we know they are coming. For exquisite details – the string score that slashes through Psycho, nature’s terrifying choreography in The Birds, the historical byways that delude us in Vertigo. And all the scenes that haunt us long after the lights go up.

Phantoms of the Cinema

Gaston Leroux’s The Phantom of the Opera (Le Fantome de l’Opera, 1909-1910) may not be great literature, but it is a unique record of the most important social and artistic institution in the “capital of the nineteenth century”, Paris. More significant still, since the novel’s publication it has radically transcended that historical-geographical specificity and become the object of constant creative re-interpretation all over the world. Nowhere is this more compellingly illustrated than in the fifty-plus screen adaptations – silent films and talkies, horror films and musicals, cartoons and tele-novelas and more – that have been made in places as far apart as Hollywood, Brazil and China between 1916 and today. Cine Fan is proud to share a significant selection of these films, starting with the enormously influential 1925 Hollywood adaptation, complete with a full score and color tinted footage, and ending with a double bill of ‘quasi-musicals’: Brian De Palma’s Phantom of the Paradise (1974), and The Phantom Lover (1995), starring Leslie Cheung. The latter may well be said to be a remake of an older, Chinese-language adaptation: Maxu Weibang’s Song at Midnight (1937), arguably the first Chinese horror and billed as “the most fascinating and creative of all interpretations of Gaston Leroux’s horrid tale” (David Robinson). Song at Midnight resurfaced in the West in the late 1990s along with its sequel Song at Midnight, Part II, made in 1941 at the height of the Sino-Japanese war. Cine Fan presents both Maxu’s adaptations in newly-restored versions, followed by a seminar with film and music scholars. – Giorgio Biancorosso Co-presented with “Screen Adaptations of Le Fantôme de l’Opéra: Routes of Cultural Transfer”, an International Research Network funded by The Leverhulme Trust (UK).