2020

The Dreamlike Tableau of Sergei Parajanov

Artistically, there are few people in the entire world who could replace Parajanov. Nothing could [...]

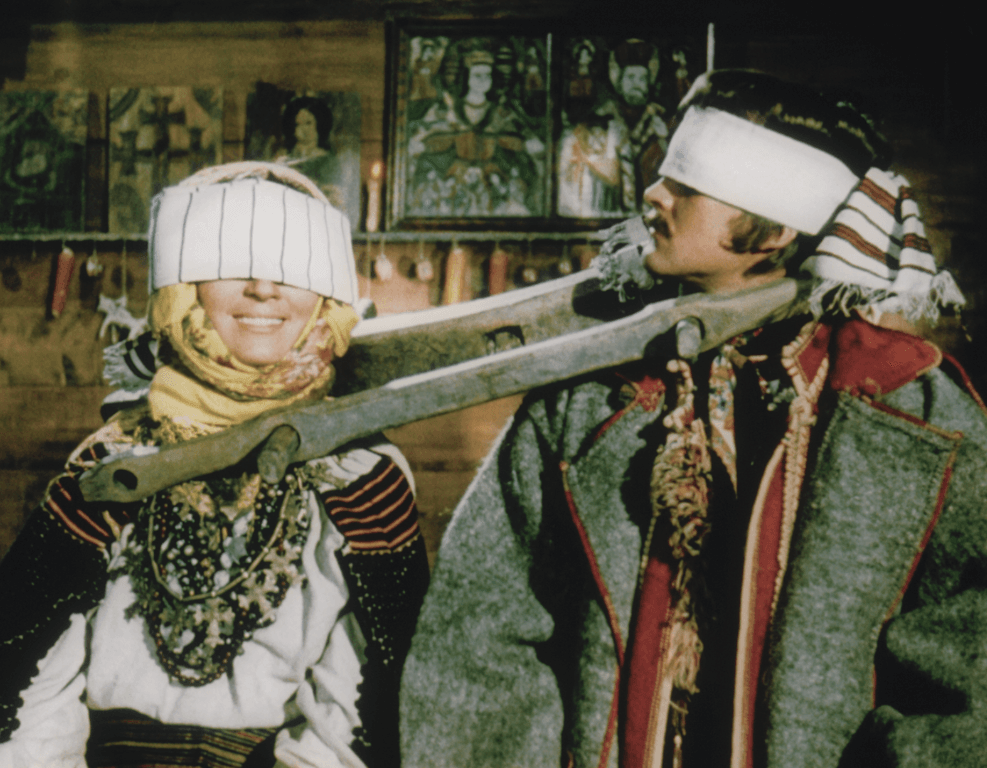

Artistically, there are few people in the entire world who could replace Parajanov. Nothing could speak more highly of Sergei Parajanov’s (1924-1990) artistry than Andrei Tarkovsky’s compliment. In serendipity, it was Tarkovsky’s Ivan’s Childhood (1962) that brought an artistic awakening to the Armenian director, who had already made films in the vein of the government-sanctioned social realist style by the early 1960s. Denouncing all of his previous works, Parajanov unleashed a new cinematic language in 1964 with Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors. Poetic and gorgeously mystical, it was a beautifully melancholic love story and a stunning love letter to Ukranian Hutsul culture.

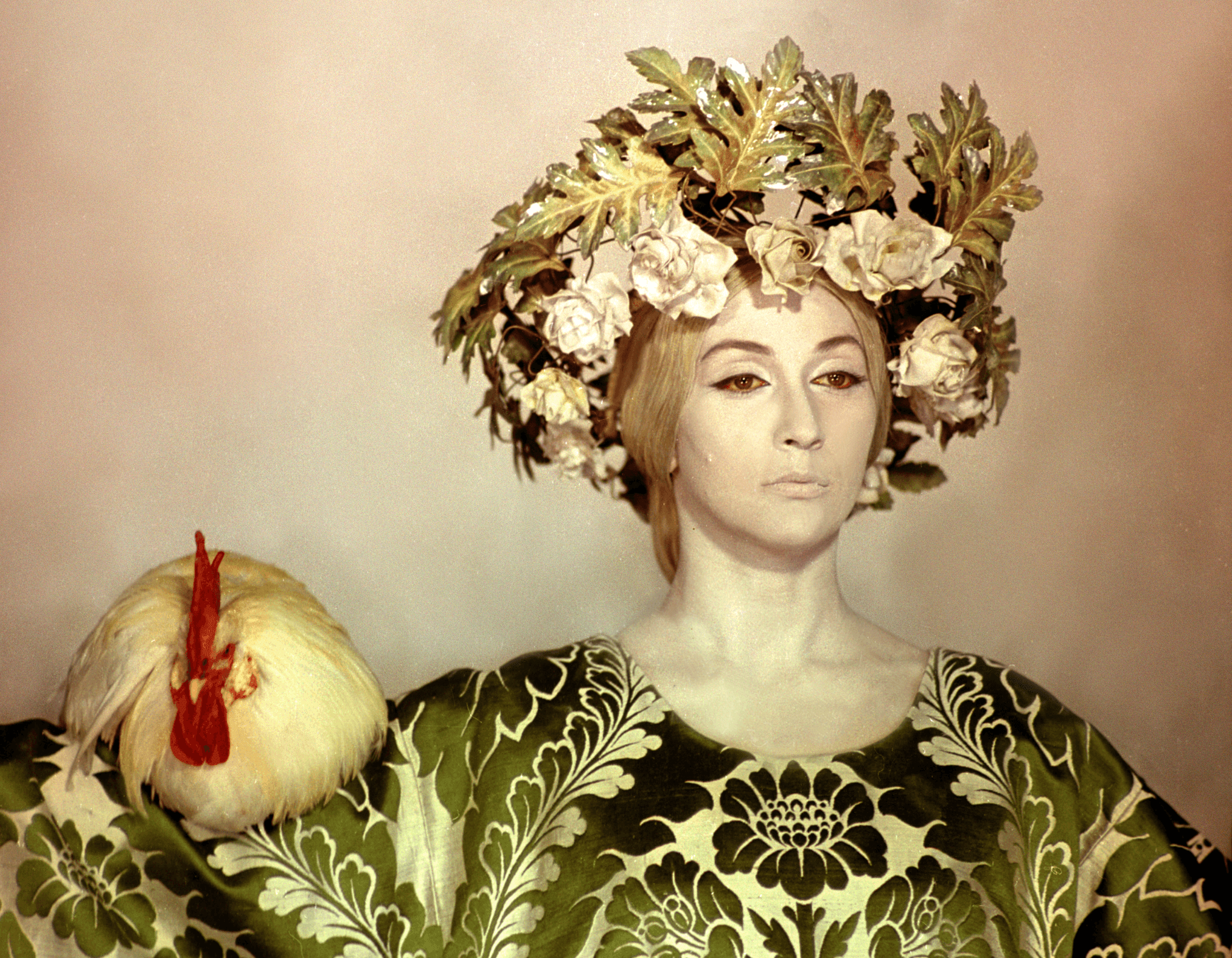

From there, Parajanov only pushed his newfound cinematic language further. He eschewed traditional narrative, crafting films made up of carefully composed tableaux that drew heavily from traditional cultures and religious symbols. It would take an entire book to decode all the symbols and specific Armenian cultural references in his masterpiece, The Color of Pomegranates (1969), but even adventurous viewers who go in blind will find an intoxicating visual feast that must be seen to be believed.

Even after the filmmaker was forced to re-edit Pomegranates to appease Soviet authorities (the restored version shown at Cine Fan is the closest version to Parajanov’s original vision) and subsequently sent to jail twice on political charges, he never wavered from his unique cinematic language. His later films, The Legend of Suram Fortress (1985) and Ashik Kerib (1988), are even more playful variations of the filmmaker’s style. The director’s visual choices may appear oddly eccentric and perhaps even random in nature, but there are no accidents in Sergei Parajanov’s world. Every movement, every word and every prop carry meaning, and every new venture into that world reveals something new.

Life is But an Illusion: The Cinema of Naruse Mikio

A master director lauded for his delicate women films, Naruse Mikio (1905-69) fathomed a woman’s [...]

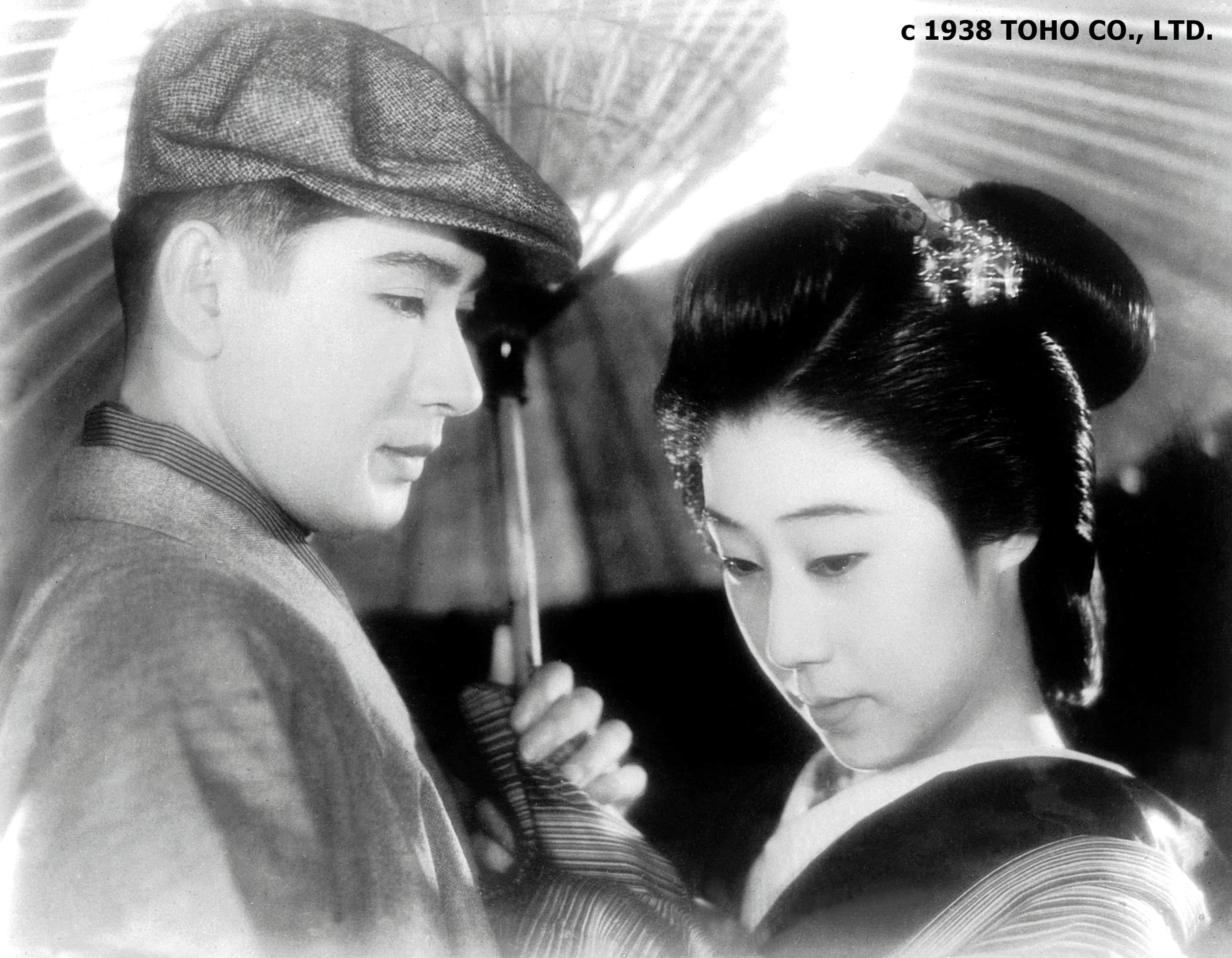

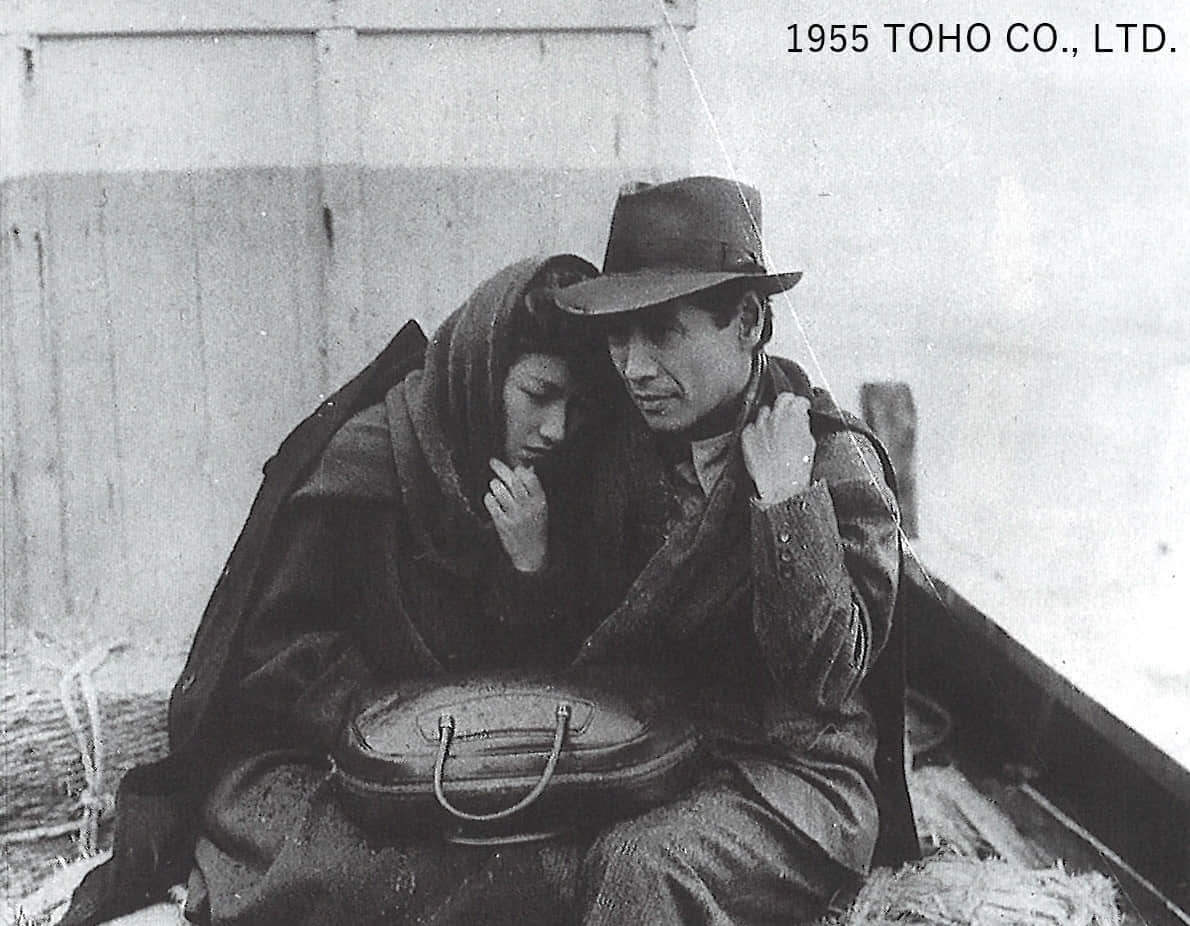

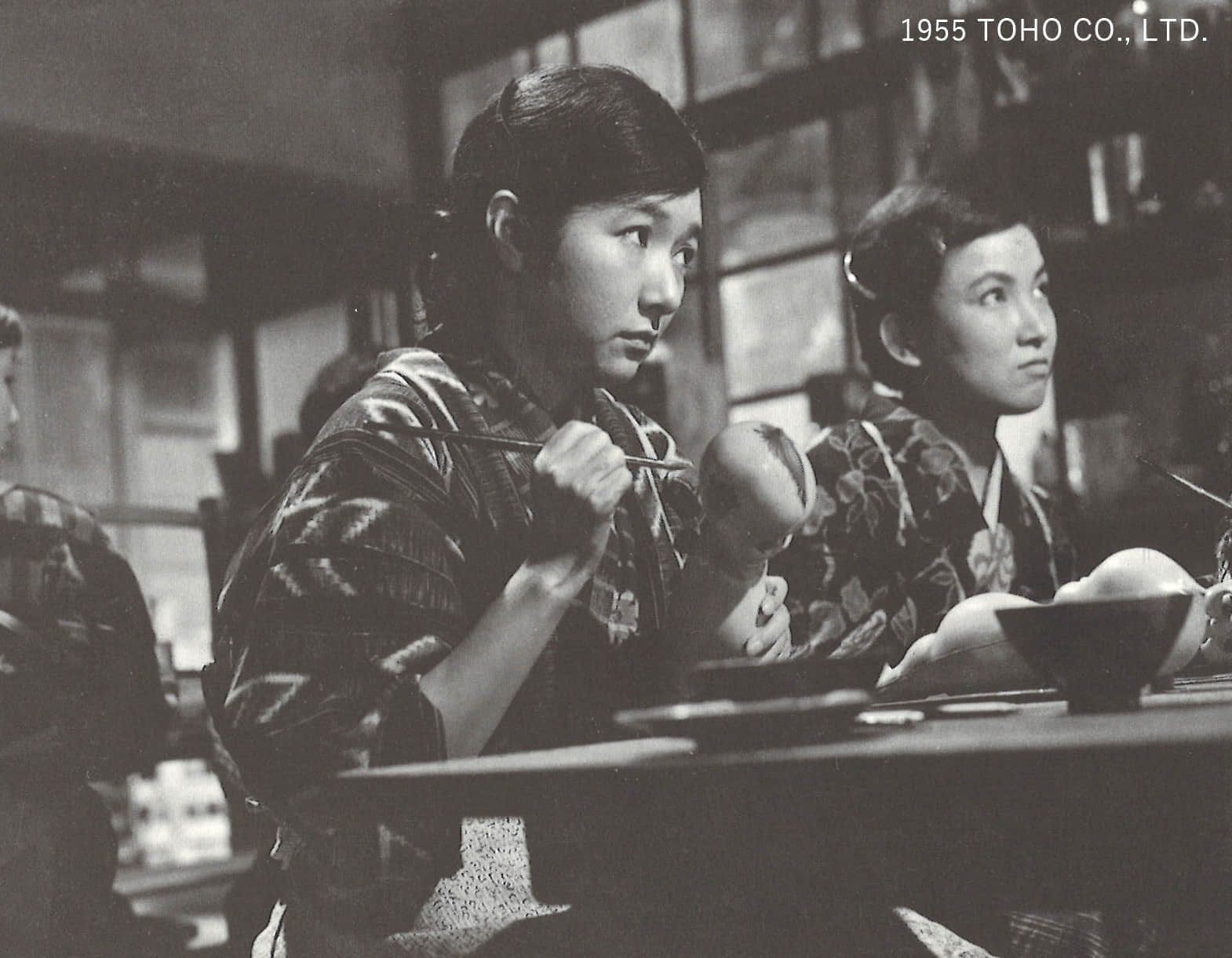

A master director lauded for his delicate women films, Naruse Mikio (1905-69) fathomed a woman’s companion is, ultimately, solitude. Most exquisitely encrypted by Takamine Hideko’s tragic death in Floating Clouds (1955), his “quiet blows to the heart” also vibrated through Yamada Isuzu’s shamisen. A towering star of the Japanese screen, she brought poise and toughness to her roles as a notable musician, a fledgling Noh dancer or a proud geisha, under Naruse’s quietly devastating camera that captures the dichotomy between artistic excellence and elusive love.

Celebrated for his realist dramas of domestic life, and his sympathetic portraits of hard-luck women, Naruse’s sensitivity to the struggles of the ordinary people is imbued with his own strife in life and filmmaking. Looking through the translucent sliding door of married couples expose the illusion of family coherence, he offered cherished space for the discontented wives to express their emotions, and profound respect for their courageous attempt to extricate from life’s hardship and oppressive relationships.

At a time when Japan experienced upheavals of war as well as societal and ideological change, Naruse’s cinema reflected his aptitude to move with the fashion of the times, representing women’s transformation in the modern milieu. Freeing herself from shattered marital promise, breaking off an exploitative relationship, or even whaling away her cheating husbands, these women are disillusioned, yet hopeful, resilient and energetic, and makers of their own destiny.

Twelve of Naruse’s classic works are housed under the roof of three creative themes – “Love / Art”, “Wife / Puzzle” and “Time / Change” – each representing his specialties in the precise delineation of artistic reflection, marital dilemmas and social vicissitudes.

Love/Art

Artists find their inspiration in love, but creative difference sets lovers apart. As to the collaboration between Naruse Mikio and Yamada Isuzu, what makes their art great – love or solitude?

Wife/Puzzle

Is marital love like fine wine, getting better with time; or like bad vinegar, turning sour as time goes by? The sweet and the bitter of being a wife, all in Naruse’s delicate cinema.

Time/Change

Floating clouds, sudden rain. In the river of time, one gesture, or one moment is all it takes for Naruse to evoke how women live and feel, in these chronicles of upheaval in modern Japan.

Tsuruhachi and Tsurujiro

Read more

The Song Lantern

Read more

Flowing a.k.a. A House of Geisha

Read more

The Flow of Evening a.k.a. Evening Stream

Read more

Feminine Melancholy a.k.a. A Woman’s Sorrow

Read more

Repast a.k.a. A Married Life

Read more

Wife

Read more

A Wife’s Heart

Read more

Floating Clouds

Read more

Untamed

Read more

As a Wife, As a Woman a.k.a. The Other Woman

Read more

Her Lonely Lane a.k.a. A Wanderer’s Notebook

Read more

Seminar on Naruse Mikio

Read more