2019

The Elusive Enchantment: Dietrich x Sternberg

Donning a top hat, slipping into a tailcoat; through the haze of cigarette smoke, she sings in an alluring voice with cold disdain. Here on stage is the seductive androgynous goddess – Marlene Dietrich (1901-92), who evokes desire for admiration, and incites all to delve into the secret behind her callous egotism.

Dietrich’s coolly transformative mystique and Austrian master Josef von Sternberg’s (1894- 1969) visionary erotic aesthetics form one of the most legendary partnerships in film history, indulging audiences in the interplay of manipulation and masochism, in which men fall one after another for her like moths to a flame. Mesmerizing the world with her sultry songs in The Blue Angel (1930) and Morocco (1930), her lustrous vitality was a perfect match for the provocative roles Sternberg created for her, be it an enticing chanteuse in Blonde Venus (1932), a patriotic spy in Dishonored (1931), a femme fatale in The Devil is a Woman (1935) and the hedonistic Catherine the Great in The Scarlet Empress (1934) – to each character she brings a fresh charisma, inducing charm as much as villainy, sympathy and scandal.

“Camp is the outrageous aestheticism of Sternberg’s American movies with Dietrich,” Susan Sontag’s accolade encapsulated the six films of their collaboration during precode Hollywood, just at the dawn of the Hays Code. Bringing European sensibility and a style so expressionistic to American screens, the lyrical filmmaker heightened his muse’s allure with chiaroscuro lighting, extravagant costumes and dazzling decors, conjuring dream visions of exotic settings from Morocco to Shanghai and even Imperial Russia. These romantic fantasies construed a delirious world of passions that overcomes strict realism and becomes landmarks of the cinematic art.

“It took more than one man to change my name to Shanghai Lily,” she says in Shanghai Express (1932). But it only took Sternberg alone to transform Marlene Dietrich into a myth – and all of us into prisoners of their grandiose illusions.

Always a Rebel, Andrzej Munk

An unsung hero of the anti-heroic trend of the Polish school, Andrzej Munk (1920-61) remains one of the most influential voices in European cinema, despite having just made four feature films in his lifetime. That’s not only because Munk is a brilliant cinematic stylist [see the complex narrative structure of Man on the Tracks (1957) or the jump cuts in Bad Luck (1960) for examples]; it’s also because he was a playful rebel who cleverly used cinema as his tool of dissent and question important issues.

Even before he began his feature film career, Munk made documentaries that went against the mainstream propaganda-esque tone. With fictional narratives, the director continued his subversive streak in even more creative ways.

Going against typical mystery narratives, neo-realistic drama Man on the Tracks sees its investigators spending most of the story exonerating a suspect instead of proving his guilt. With both Eroica (1958) and Bad Luck, Munk boldly questioned the concept of heroism with tragically ironic humor during a time when war heroes are showered with unquestioning praise. Even with his incomplete masterpiece, Passenger (1963), he took the non-traditional route by taking the perspective of the oppressor during the Holocaust.

Perhaps the most telling thing from Munk’s life is that despite his claims of being a leftist, he was kicked out of Stalinist organization Polish United Workers Party for having “right-wing tendency”. Once a rebel, always a rebel.

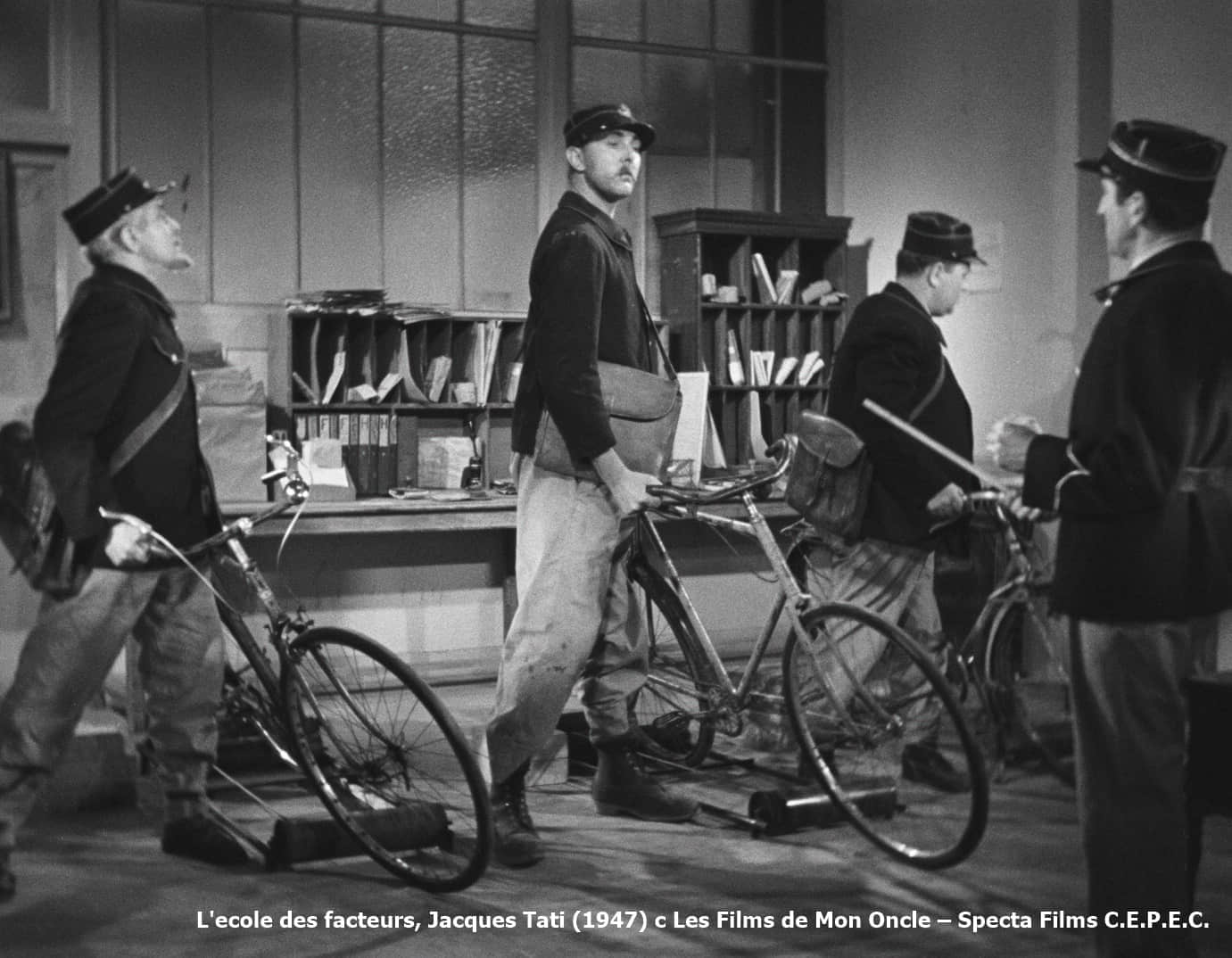

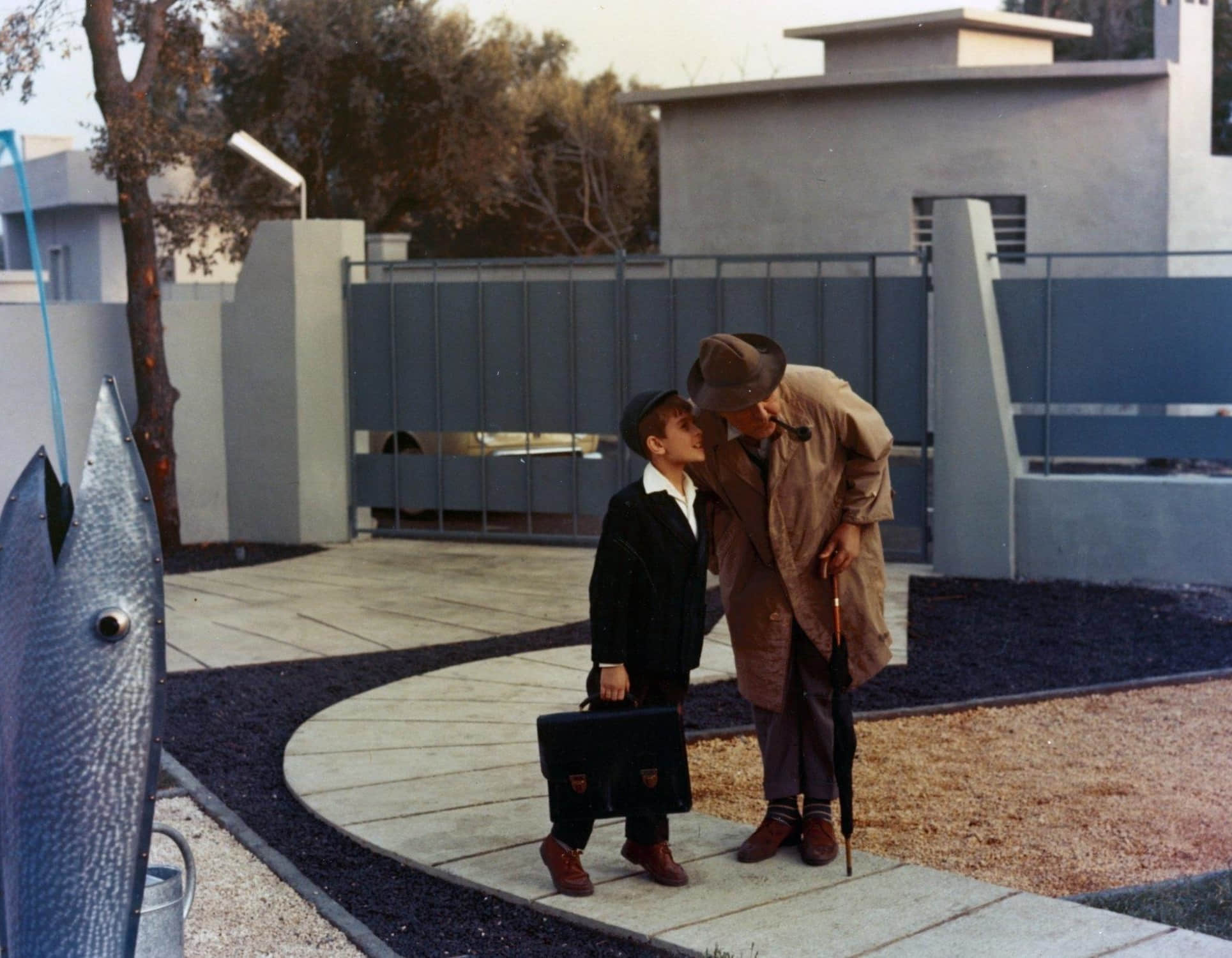

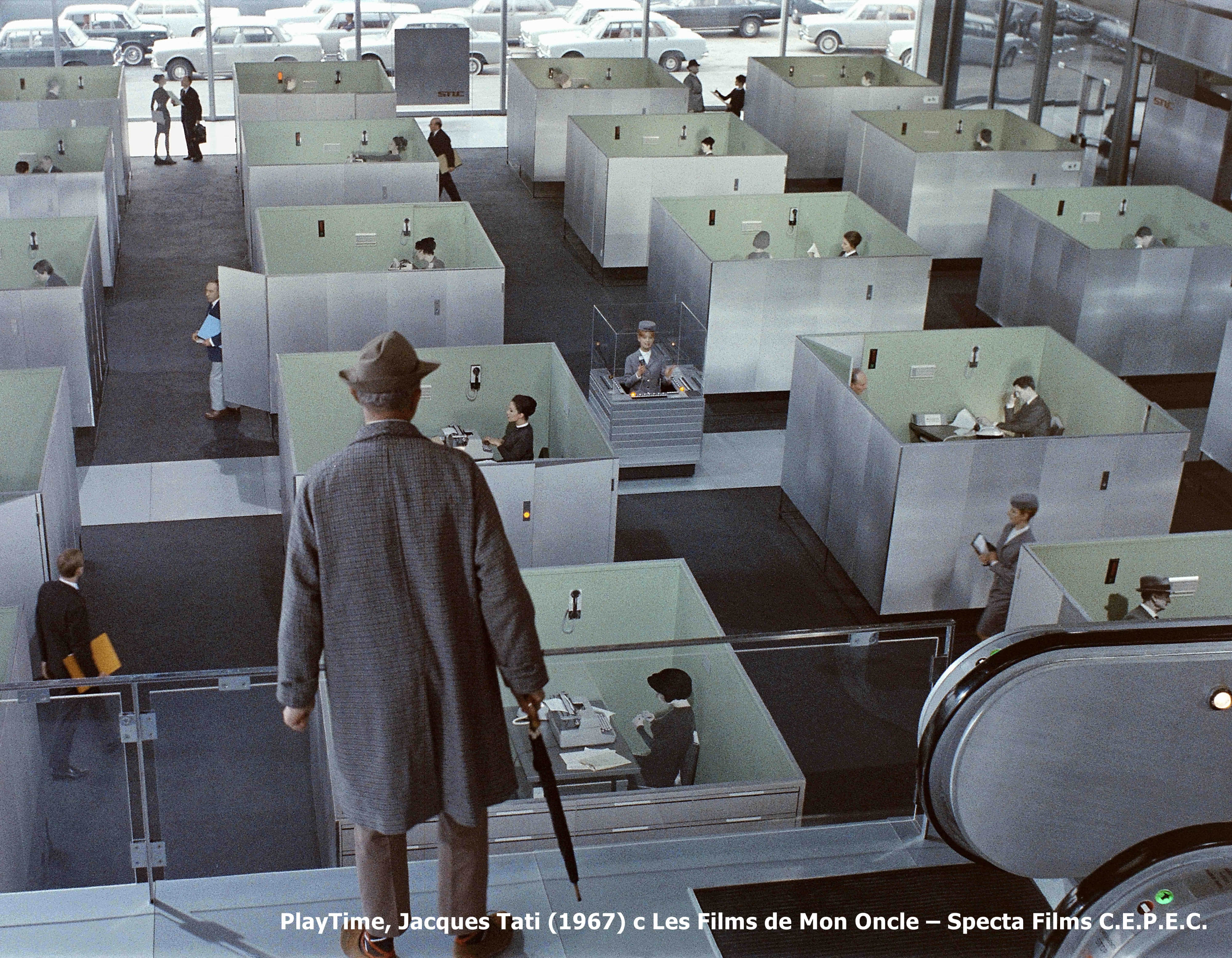

The Logic of Illusion: Jacques Tati

Universal in appeal yet unmistakably French, the comedies of Jacques Tati are not only among the greatest ever made by a performer/director in the manner of Chaplin or Keaton, but have immeasurably enriched the very language of cinema itself.

Tati bore witness to (or anticipated) the material transformation of postwar France in the midst of Europe’s economic miracle, transitioning from sleepy villages and old-fashioned neighborhoods to standardized, gadget-filled suburban housing and a high-tech Paris rebuilt almost beyond recognition – emblems of the new consumer society that brought with it the dreaded threat of Americanization. The remarkable art of Jacques Tati consists not only of his own comic turns as the iconic Mr. Hulot – a tall, charmingly awkward figure seen always with hat, raincoat, and pipe, ill-adapted to modern society with his oldfashioned ways – but with his uniquely cinematic form of humor. A master at staging in depth, Tati’s mise-enscène fully exploits his characteristic wide-shot compositions by positioning gags in every conceivable nook and cranny of the frame, from background to foreground, requiring an alert viewer’s active participation in visually registering the humor.

Individual gags often function like motifs in a musical composition. Loosely episodic, the films’ narratives are hardly plot-driven, but allow for a leisurely observation of the comedy in the minutiae of daily life. Notably, Tati sought to “democratize” his narratives by focusing less on a central character, than to find humor in passers-by peripheral to the narrative.

For all of Tati’s visual imagination, however, don’t forget the sound: there may be little dialogue, but the funny manipulation of everyday sounds (and fragments of speech) forms a musique concrète-like soundtrack sure to tickle the most curmudgeonly of viewers. In sum, Tati represents film comedy at its purest: as formal abstraction.