2019

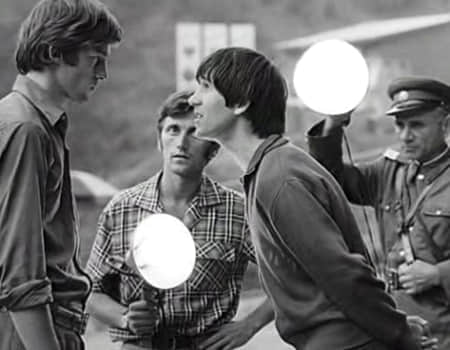

Absurdistan: The Central and Eastern European Cinema of the Absurd

Welcome to Absurdistan.

The Czech term conjures up a distant nonsense land. But the word refers to the absurdities homegrown in the Czechoslovak and other socialist republics of Central and Eastern Europe, from the end of World War II until – for most of these countries – the revolutions of 1989.

This programme marks the 30th anniversary of the liberation of the former socialist republics from their repressive governments. We are screening restored films from Ukraine, Hungary, Poland, Romania and former Czechoslovakia. The shared sensibility of the absurd unites these diverse nations, and their films from documentaries to sci-fi, allegory, satire and multi-media animations.

The Central and Eastern European sense of the absurd brewed over the centuries when peoples of the region could not determine their fates. The absurd overflowed in the gaps between the ideals and realities of their socialist states: between the happiness they were supposed to enjoy and the material hardships they faced; the failure of basic services, strictures of official culture, pretenses of public life, physical and spiritual confinement, ruin of the landscape, fantasies of escape and the search for daily dignity within regimes that refused to admit any flaw. Unlike the idea of the absurd in Western Europe, the absurd in the East was a personal, concrete and everyday experience.

These films evoke the liberties that Central and Eastern Europeans only intermittently enjoyed in the 20th century and that again feel fragile in the 21st. Each film resonates beyond the system that created it, to show how remote certain rights once were and how precarious they remain. Glossy or stark, scathing and playful, these films express the ludicrousness of authoritarian rule through creative varieties of absurdity.

Guest Programmer: Gabriel M. Paletz

Gabriel M. Paletz earned the first PhD at the University of Southern California in film studies with a minor in film production. He has since taught filmmaking from the Czech Republic to Ethiopia, curated film series from Kosovo to Hong Kong, and is now finishing a book on Orson Welles.

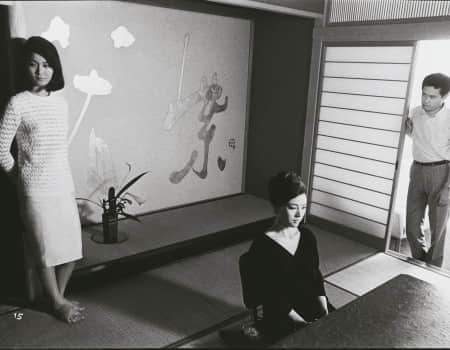

The Beauty of Sadness: Kawabata Yasunari

“His narrative mastery, which with great sensibility expresses the essence of the Japanese mind” – [...]

“His narrative mastery, which with great sensibility expresses the essence of the Japanese mind” – Nobel Prize’s commendation epitomized the greatness of Kawabata Yasunari (1899-1972), the first Japanese novelist bestowed the distinguished literature award.

A melancholic lyricism echoing ancient Japanese literary tradition infused with European literary aesthetics, Kawabata’s works are permeated with a sense of loneliness and a preoccupation with death. Reminiscent of the fluid composition of renga poetry, his writings capture the free-flowing nature of life, intertwined with beauty, sincerity and sadness.

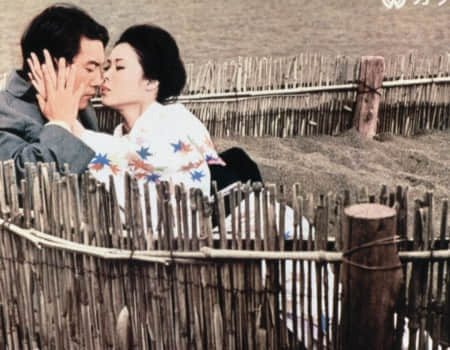

Sound of the mountain, snow in a country, forest in the old capital… the beauty of landscapes is connected with the emotions of his characters. The long and winding road in Mr Thank You (1936) is reflective of life’s vicissitudes; and the temple bell in With Beauty and Sorrow (1965) awakens suppressed emotions and longing for a love foregone.

Keen perception, deceptive simplicity and the deep melancholy that characterize Kawabata’s masterpieces become inspirations for generations of filmmakers. From the Golden Age to contemporary Japanese cinema, a range of acclaimed directors have created a fascinating filmscape of transcendent beauty and meditation in their adaptations.

In the form of pure love, or love unattainable, lies the ideal of unusual artistry and truth – personified by the legendary actresses. The irresistible charm of Okada Mariko transformed the profound sensuality in Woman of the Lake (1966); and the sublime elegance of Iwashita Shima gave a real-life grace to the Twin Sisters of Kyoto (1963).

Kawabata’s ingrained Japanese aesthetic traditions – tea ceremony, flower arranging, and ultimately the Zen spiritual values – are visualized under exquisite imagery. Through Tanaka Kinuyo’s tears (The Dancing Girl of Izu , 1933), Wakao Ayako’s death (Thousand Cranes , 1969) – and maybe his own suicide – the great writer’s quest for purity of life is finally realized. And reborn in Nirvana

35mm prints of The Dancing Girl of Izu , Mr Thank You, Thousand Cranes (1953), With Beauty and Sorrow, Woman of the Lake and Thousand Cranes (1969) courtesy of the National Film Archive of Japan.

35mm print of Snow Country and 16mm print of Twin Sisters of Kyoto courtesy of The Japan Foundation.

The Dancing Girl of Izu

Read more

Mr Thank You

Read more

Thousand Cranes (1953)

Read more

Sound of the Mountain

Read more

Snow Country

Read more

Twin Sisters of Kyoto

Read more

With Beauty and Sorrow

Read more

Woman of the Lake

Read more

Thousand Cranes (1969)

Read more

Seminar on Kawabata Yasunari Film Adaptations

Read more