2019

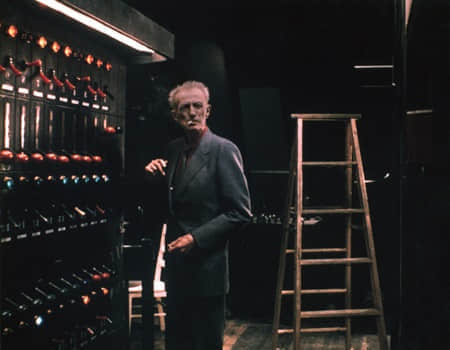

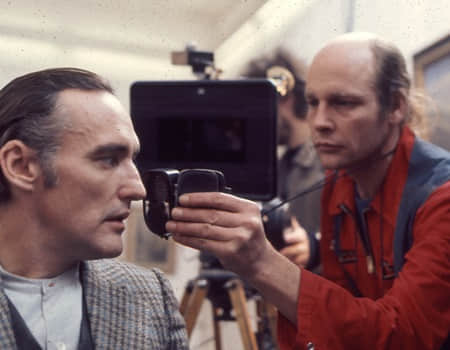

Nicholas Ray, The Rebel Interrupted

A modern auteur who transcended classical narrative conventions through his distinctive mise-enscène – lyrically abstract [...]

A modern auteur who transcended classical narrative conventions through his distinctive mise-enscène – lyrically abstract and pushing to a paroxysm such forms of social suffering as alienation, solitude, and violence – Nicholas Ray (1911-1979) offered the most passionate, honest, intimate and personal views of the American society and its people, complete with the contradictions and illusions that contrasted sharply with the official image of postwar prosperity. The young French film critics from the Cahiers du Cinéma were the first to recognize the talents of this maverick to reinvent filmmaking from within the industry. Back home, the revered Andrew Sarris ranked Ray among the top of the nation’s auteurs. Ray’s debut feature, They Live by Night (1948), immediately announced his cinematic innovation and brought him to attention by Hollywood giants. A quintessential American director, he worked at nearly every studio in Hollywood, filming in virtually all genres without ever compromising what Eric Rohmer once described as “his own style, his own vision of the world, his own poetry.” This period also coincided with Hollywood’s transition to color and adoption of CinemaScope, and Ray was a master at both, his widescreen compositions are filled with volatile energy and the intense, expressionist use of colors. This series focuses on Ray’s greatest works, from contemporary dramas such as Rebel Without a Cause (1955) and Bigger Than Life (1956) that critique the conformist pressures of suburban life in Eisenhower-era America, to unusual takes on genre like the female-driven political Western Johnny Guitar (1954). Ray’s final film in collaboration with Wim Wenders will also be screened. As Godard once famously proclaimed: Henceforth there is cinema. And the cinema is Nicholas Ray.

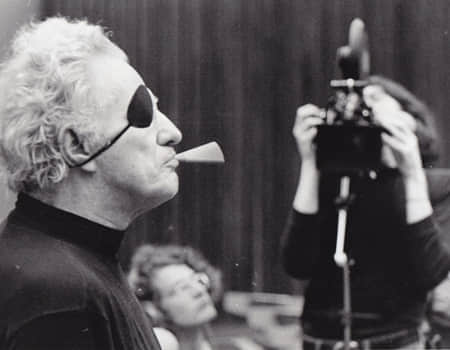

Robby Müller: Let’s Make Light

Underlying the most transcendent images ever captured onscreen – the desolate splendor of Wim Wenders’ [...]

Underlying the most transcendent images ever captured onscreen – the desolate splendor of Wim Wenders’ road movies, or the raw aesthetic of Jim Jarmusch’s deadpan comedies – are the work of Robby Müller (1940-2018), the Dutch cinematographer who helped shape the filmmakers’ visions. “He’s like a Dutch interior painter, like Vermeer or de Hooch, who was born in the wrong century,” observed Jarmusch. With an instinctive acumen for natural light, Müller maintained a philosophy of simplicity – “the magic of the film image depends upon the viewer believing in the reality of the light.” His ingenuity was more than creating a cinematic authenticity, but grounding his shots with deep humanity. His camera was a window to the soul. His inventive use of light, his intuitive sense of framing, and the lyricism of his camera movements created an enduring visual language that helped filmmakers establish their signatures. From The Goalkeeper’s Fear of the Penalty (1972), Wenders embarked his cinematic journey with Müller, delivering features that filtered the mythology of American culture through a prism of European alienation, exemplified in the Cannes Palme d’Or winner Paris, Texas (1984). Be it the eerie blues in Mystery Train (1989), or the highcontrast monochrome in Dead Man (1995), Müller’s entrancingly poetic imagery is a perfect complement to Jarmusch’s idiosyncratic style. He never lost his appetite for innovation – transcending the suburban scenery into a woman’s landscape of isolation in Peter Handke’s The Left-handed Woman (1978); transforming sleazy bars into iridescent catacombs for Barbet Schroeder’s Barfly (1987); and employing handheld cameras to stunning effect in Lars von Trier’s Breaking the Waves (1996) and another Palme d’Or winner Dancer in the Dark (2000). A man who changed the face of cinematography, Müller will continue to shine a light in the darkness of cinema.