2023

Crimes and Misdemeanours – The Eccentric Cinema of the Coen Brothers

‘I got horse sense, goddamnit. Showmanship!’ Hollywood executive Jack Lipnik explains to scriptwriter Barton Fink why he [...]

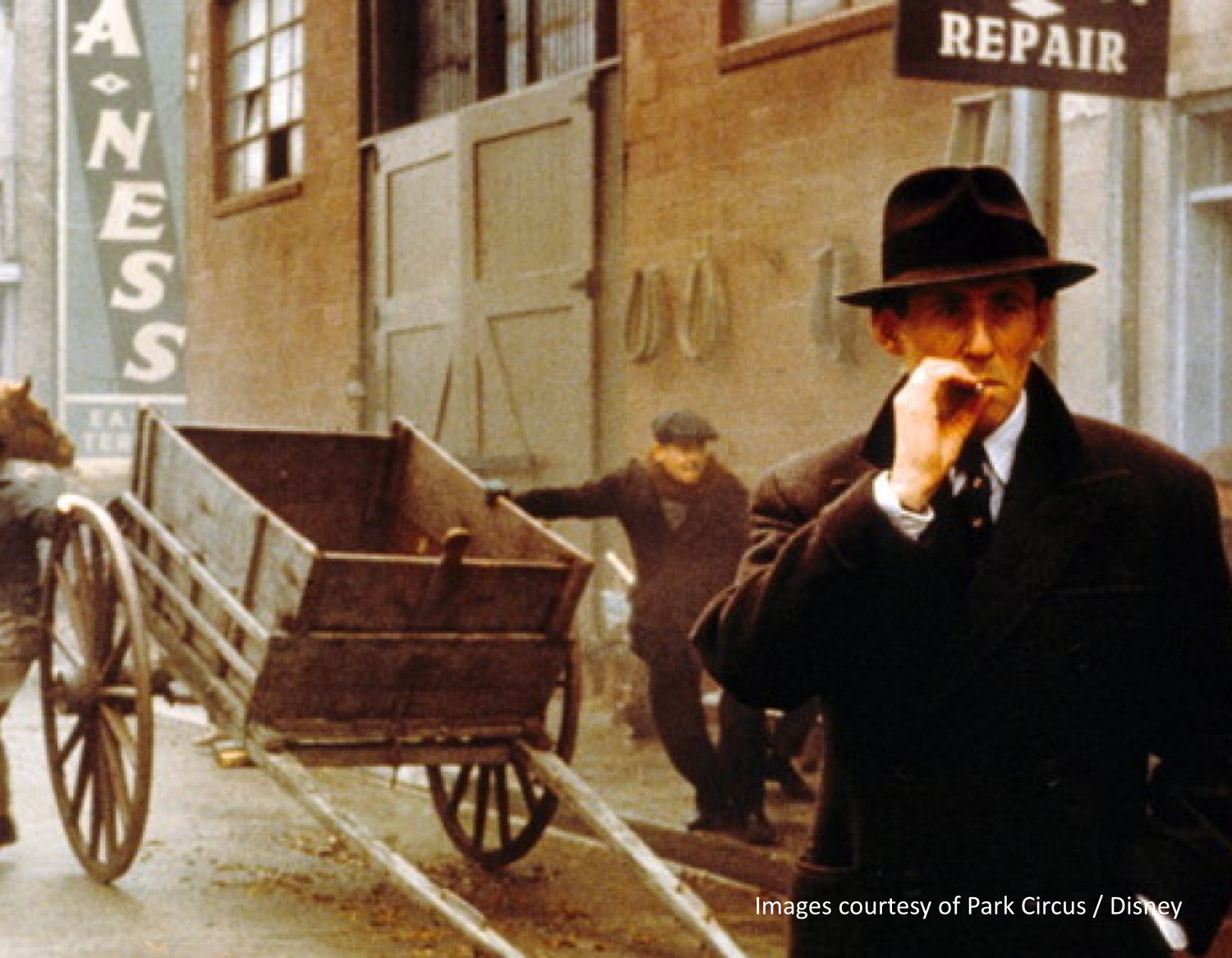

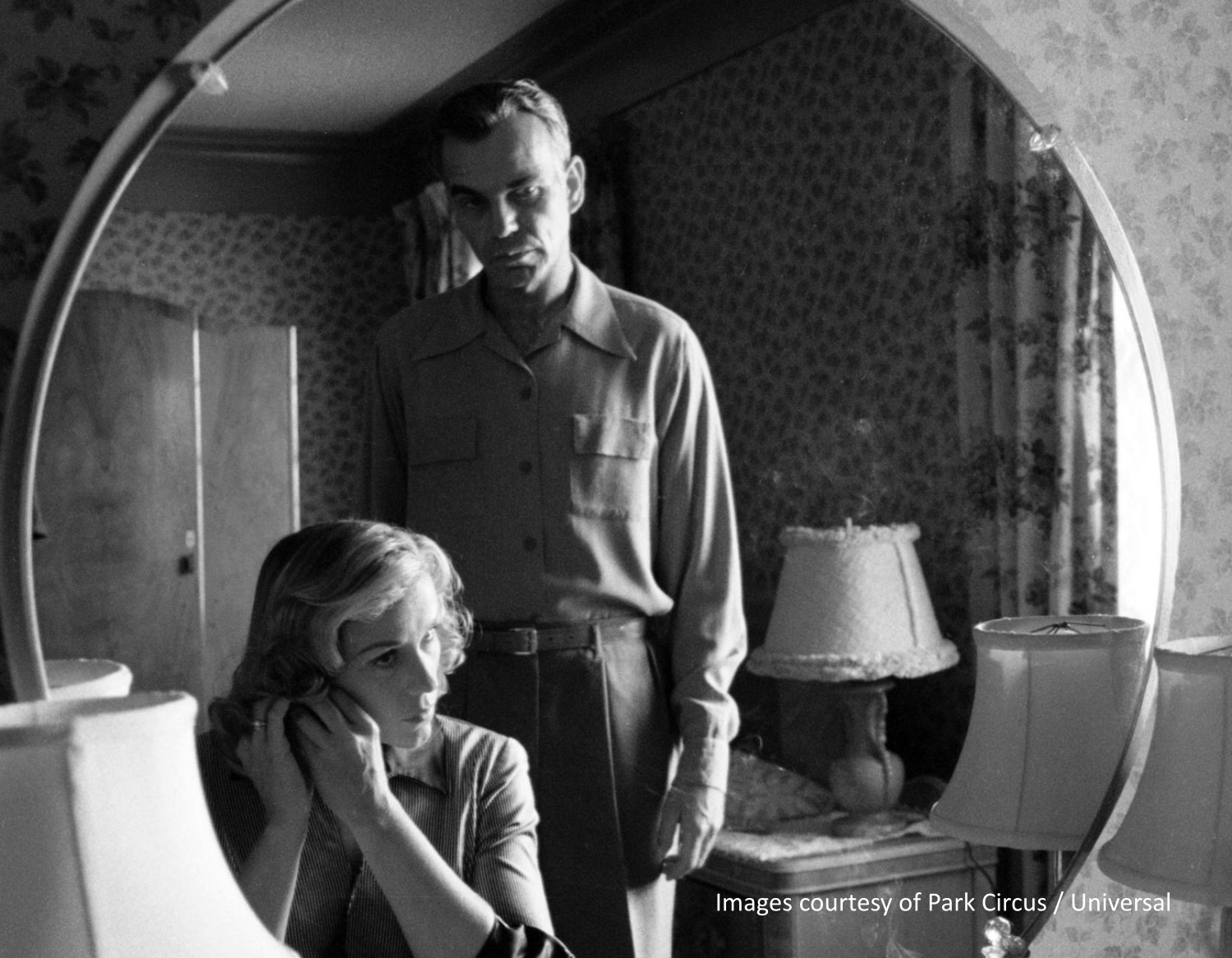

‘I got horse sense, goddamnit. Showmanship!’ Hollywood executive Jack Lipnik explains to scriptwriter Barton Fink why he is so successful despite not knowing the scripts. Indeed, such deprecatory, ironic jokes are pitch-perfect creation of Joel and Ethan Coen, who are recognised as masters in the art of scriptwriting – and in the subversion of Hollywood protocol.

Never run out of creative ideas, the Coen Brothers make a bold definition of ‘Coenesque’ storytelling with their flawless blend of offbeat narrative, tricky twists and turns, dark humour and memorable characters, all wrapped up in a meticulously structured script enhanced by a measured camerawork – thanks to long-term cinematographer Roger Deakins. The duo has managed to explore a wide variety of genres while maintaining the playfulness to topple storytelling conventions.

In a career spanning close to forty years, the Coens have crafted a distinctive cinematic universe all their own. It’s a world that fills with boisterous eccentrics, wily criminals and desperate artists who are often ill-equipped to meet the challenges thrust upon them. Above all, fate dictates a powerful dynamic at play. Be it Dude in The Big Lebowski , Ed in The Man Who Wasn’t There, Norville in The Hudsucker Proxy, they are free to dream and scheme, but at the end of the day, it’s fate that holds them back – all except the amazing female characters. Exemplified by Frances McDormand, the formidable actress and wife of Joel Coen, women are strong, defiant, and self-assertive, taking destiny into their own hands.

Rich in historical detail, while existing just the other side of grounded reality, the vivid filmography of the Coens represents the United States as a nation of immigrants, beholden to their roots. Whether unfolding on the streets of Manhattan or the deserts outside El Paso, the Coens feel equally comfortable addressing the lingering woes of a nation where the American Dream has emboldened so many to make their fortunes outside of the law. Recurrent themes of infidelity, betrayal, opportunism and greed; omnipresent motifs of typewriters, telephones and revolvers are given freshness and spontaneity that both reinforces and elevates the comedic and horrific effects.

‘Yeah, well, that's just, like, your opinion, man.’ The Dude opts not to argue about it, and continues with the game. So do the Coens, don’t they?

Cinema Heritage: From The Film Foundation

Too Absurd a Reality: A Jiří Menzel Retrospective

One of the defining voices of the Czech New Wave, Jiří Menzel’s life (1938-2020) itself embodied the [...]

One of the defining voices of the Czech New Wave, Jiří Menzel’s life (1938-2020) itself embodied the tumultuous and troubled history of his homeland for over half a century.

Born only months before the country was occupied by Nazi Germany, Menzel grew up during World War II and spent much of his life behind the Iron Curtain. Despite working under monitoring and censorship, he looked at the constraints in a different way: ‘Freedom has this unlucky side effect that by making everything possible, you lack purpose and a direction. Creation always needs limits.’ Channeling his fearlessness into artistic force, Menzel co-directed Pearls of the Deep with Věra Chytilová, Jan Němec, Jaromil Jireš and Evald Schorm in 1965, recognised as a manifesto of the Czech New Wave. The movement was made headway with Closely Watched Trains, his feature debut that quietly subverted comedy with its form and structure, leading the burst of creativity in Czech filmmaking before it was crushed by the end of the decade.

His enduring friendship and longlasting collaboration with writer Bohumil Hrabal produced one of the most fruitful cross-pollinations between cinema and literature. Menzel’s Czech New Wave realism intertwined with Hrabal’s cynic satire to render a unique blend of cinema – comedic, whimsical, and sharing a humane and inquisitive worldview. Translating five of Hrabal’s novels into feature films with his skilful use of sound and poetic image, Menzel created portraits of memorable characters – the sexually naive train dispatcher, the unruly bourgeois dissidents and the quirky, aspiring waiter – that delve deeply into human relationships, morality, and the absurdity of life under totalitarian regimes.

Despite being prevented from working for years, Menzel insisted to stay and re-emerged to direct films focusing on the simple rural milieu. From the country folk’s off-beat fantasy and optimism, he derived his brand of comedy with a charmingly light touch and subtle irony to counter the morose state ideology, leading Czech films back to the limelight of international cinema.

‘Menzel were celebrating not only Czech identity after the murderous 20th century but his own cunning and perseverance as an artist,’ New Yorker critic David Denby’s succinct remark encapsulates the beacon of a daring spirit, who kept artistic freedom alive.

Supporter:

Special Thanks: