2023

For Ever Godard

One of the greatest filmmaking giants of all time, Jean-Luc Godard (1930-2022) seemed like an unstoppable force [...]

One of the greatest filmmaking giants of all time, Jean-Luc Godard (1930-2022) seemed like an unstoppable force of superhuman intellect who would live forever, but he finally chose to go out on his own terms. It looked as if he was having his last laugh, bidding us farewell at will, and stunned us with his last breath.

In his lifetime, he shocked and enthralled everyone when he introduced jump cut as a cinematic tool for editing, and broke the fourth wall in the middle of a sentence without hesitation. Many filmmakers were daring, few were willing to try something new, but it’s another thing to keep on breaking the rules, experimenting with cinematic forms, pushing the narrative boundaries, reinventing new sets of film language, as well as embracing new technologies. Ever since Godard made Breathless, cinema has never been the same.

Godard began writing film criticism in the 1950s for the film magazine Cahiers du Cinéma. Together with fellow critics François Truffaut, Claude Chabrol, Jacques Rivette and Eric Rohmer, they formed a group of enthusiasts who criticised the traditional ‘quality’ French cinema and believed in the Auteur Theory. These young critics would become the influential French New Wave when they began making innovative films that revolutionise the world of cinema with their agility and creativity.

Having made over 40 feature films in his lifetime, Godard inspired audiences by holding on to his independent spirit in film and in life. His career can basically be divided into four phases. During his New Wave period, one would be excited at the freshness and freedom of his filmmaking style and appreciate how he surpassed the boundaries of his narrative, and captured the charm of his muses who shone brightly in front of the camera; in his political years after the revolution of May 1968, one would be stimulated by his revolutionary spirit and unflinching passion; in his later years, one would be immensely moved and admire without reservation his abstract cinematic essays that managed to balance ideology and poetry.

In Breathless, Patricia (Jean Seberg) interviewed Parvulesco (Jean-Pierre Melville) and asked, ‘What is your greatest ambition in life?’ To which Parvulesco replied, ‘To become immortal… and then die.’ Godard did just that, and left us an unparalleled body of work, which should be understood only by experiencing, again and again.

French New Wave

Jean-Luc Godard, the leading figure of the French New Wave from the Cahiers du cinéma faction, as [...]

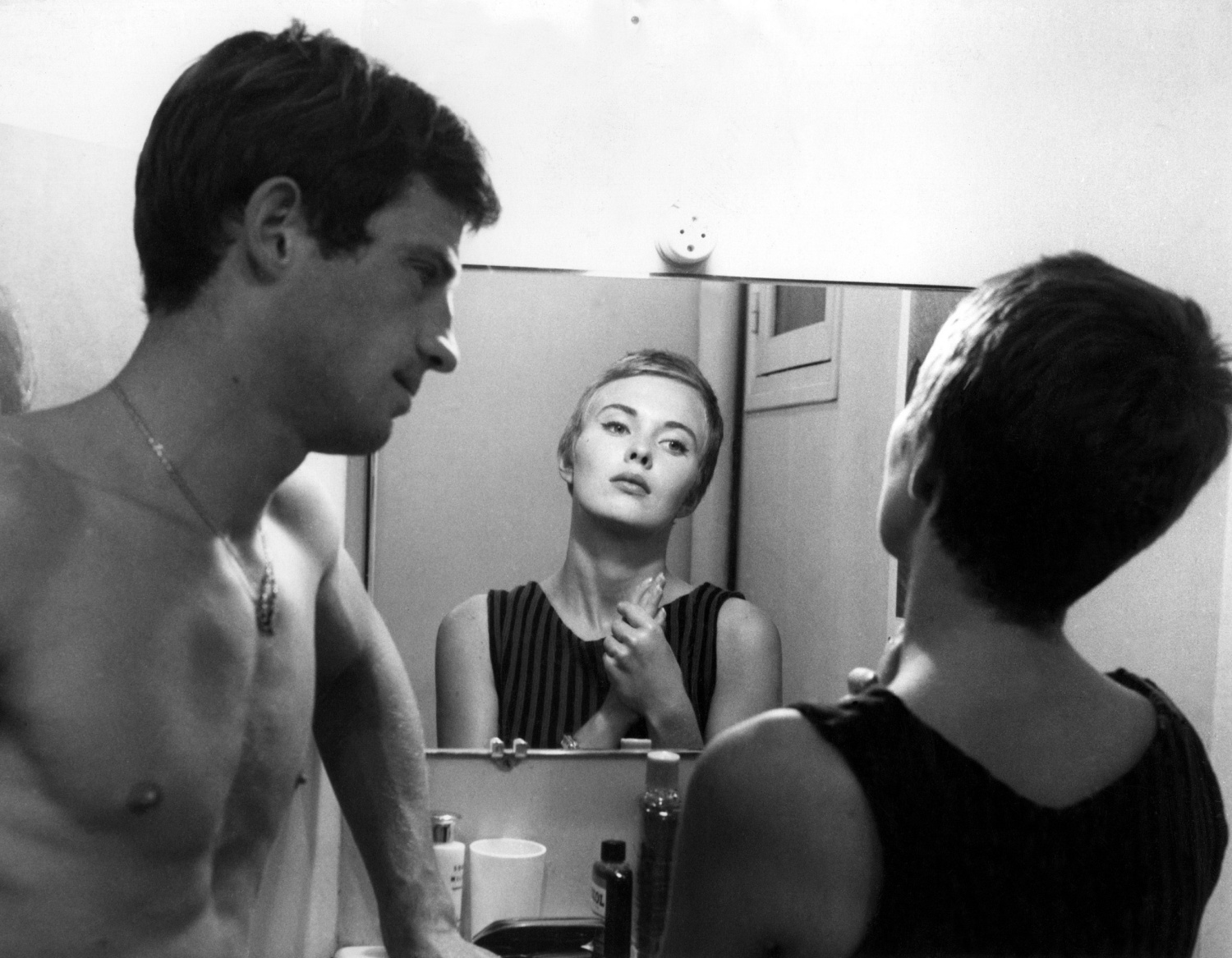

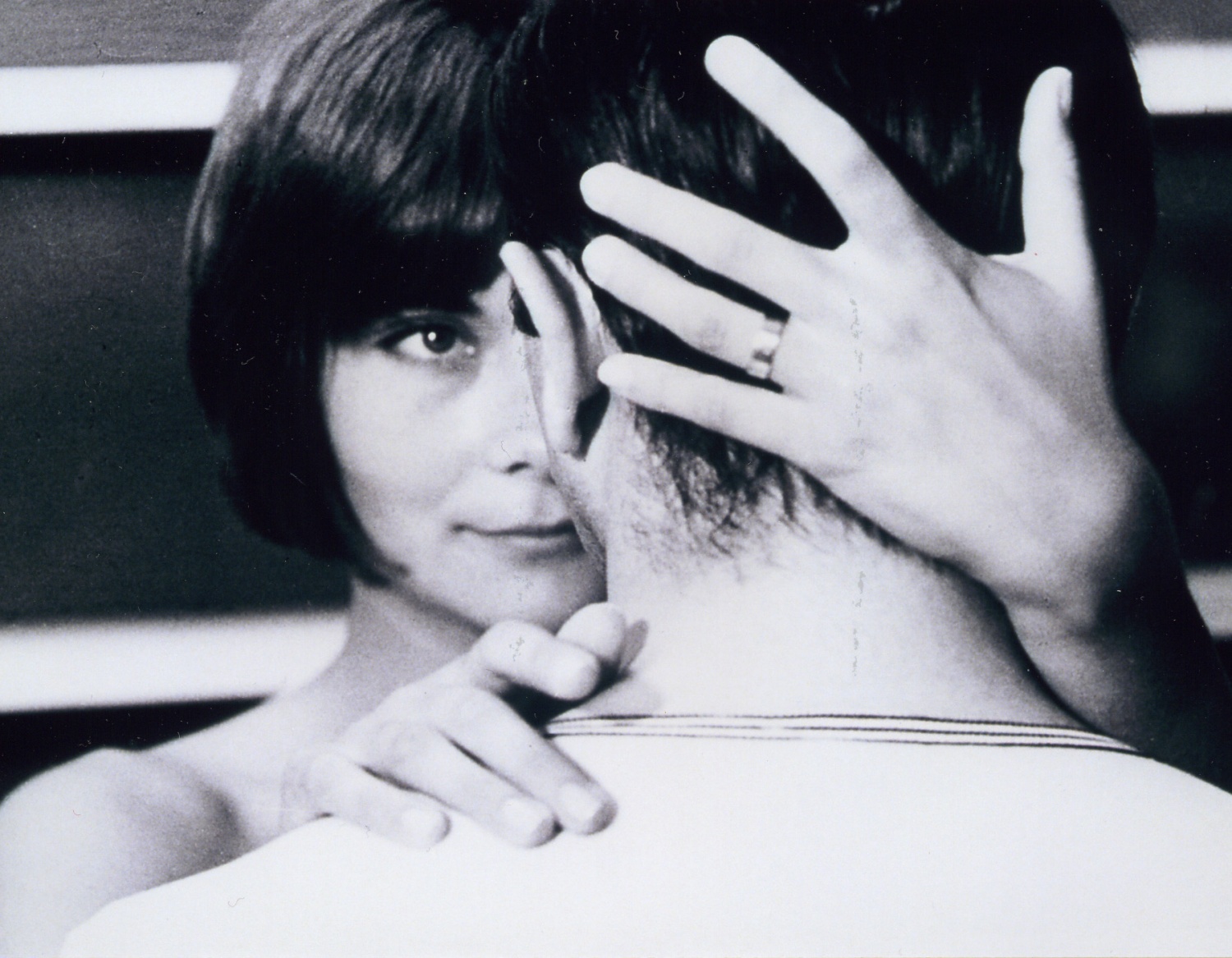

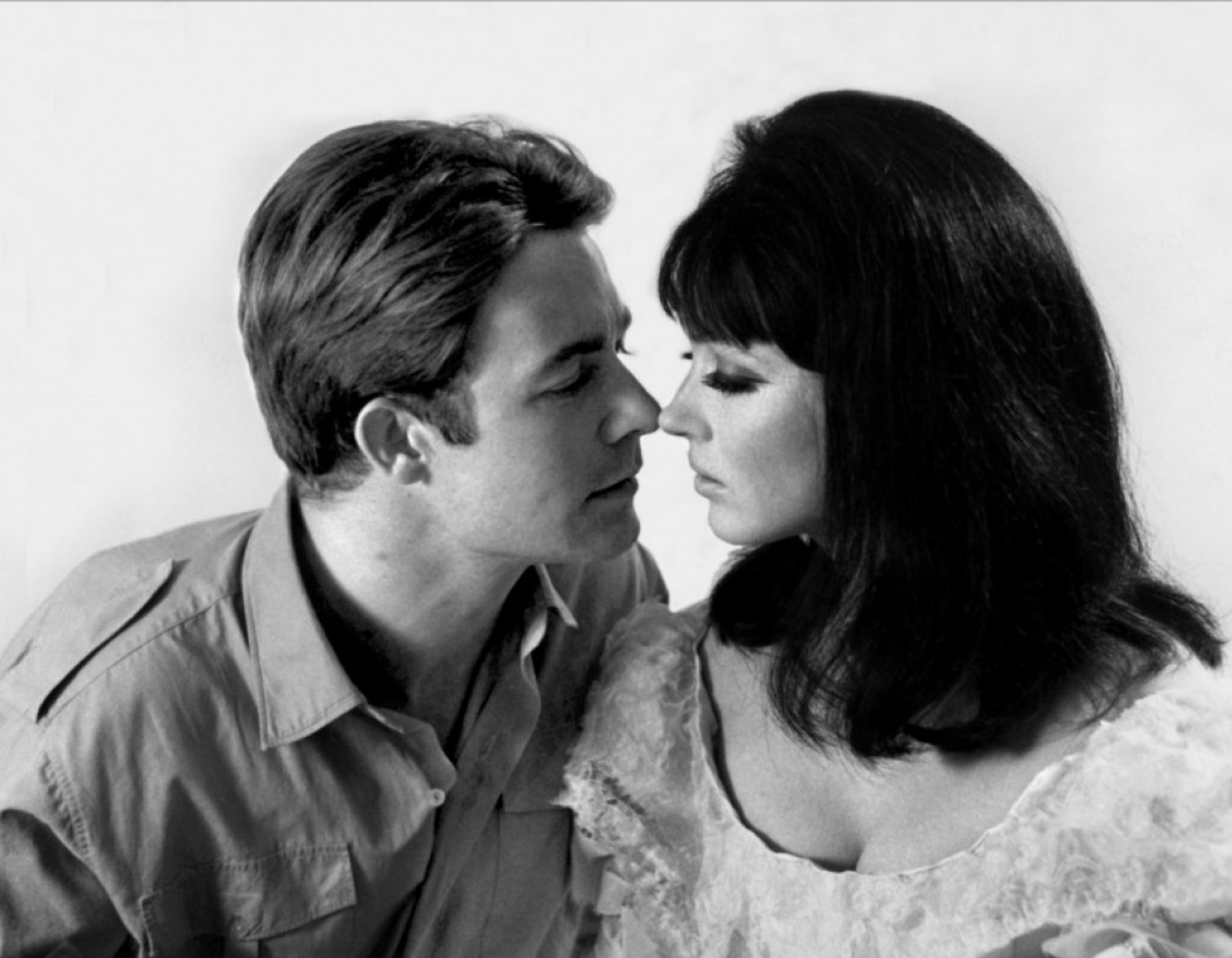

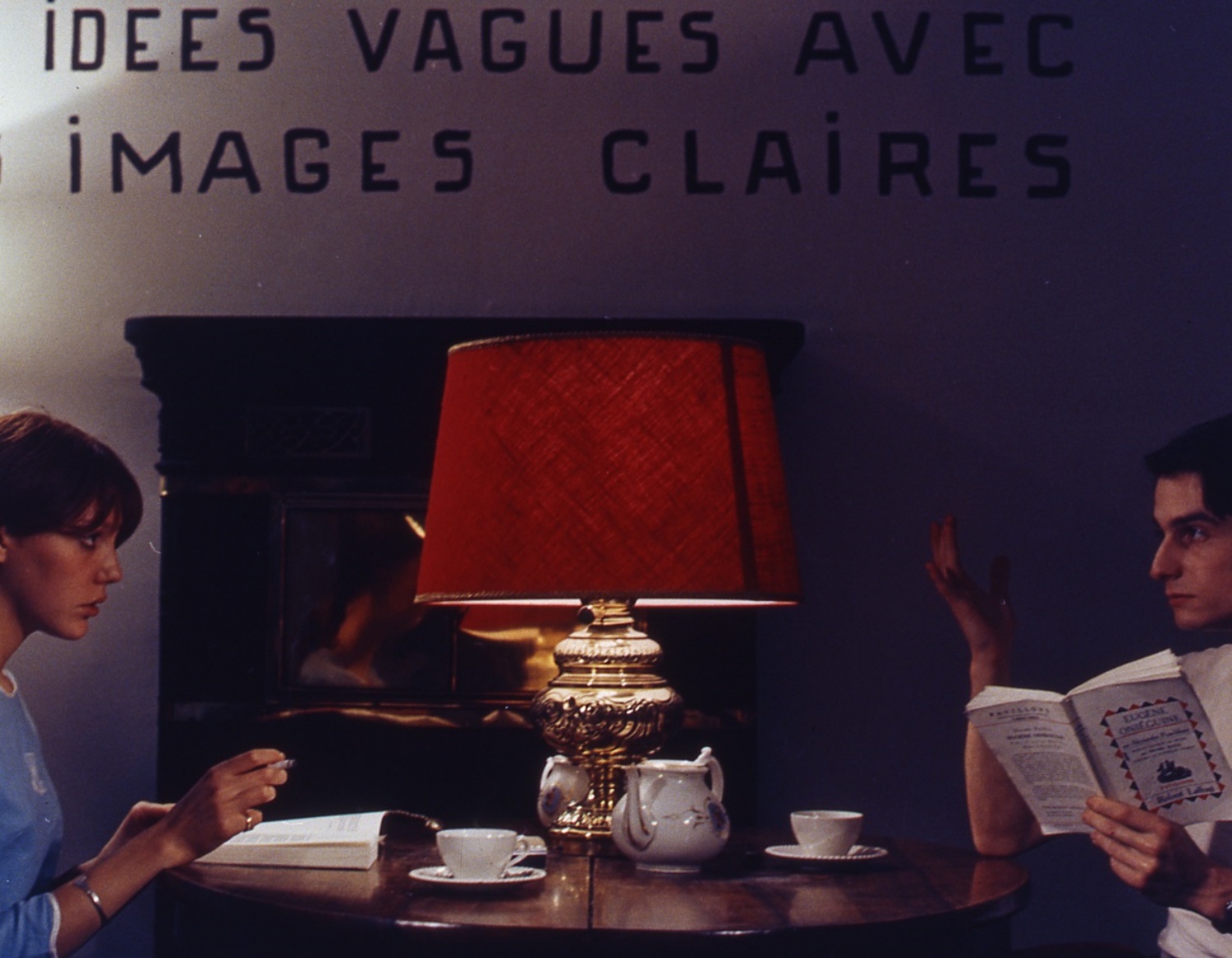

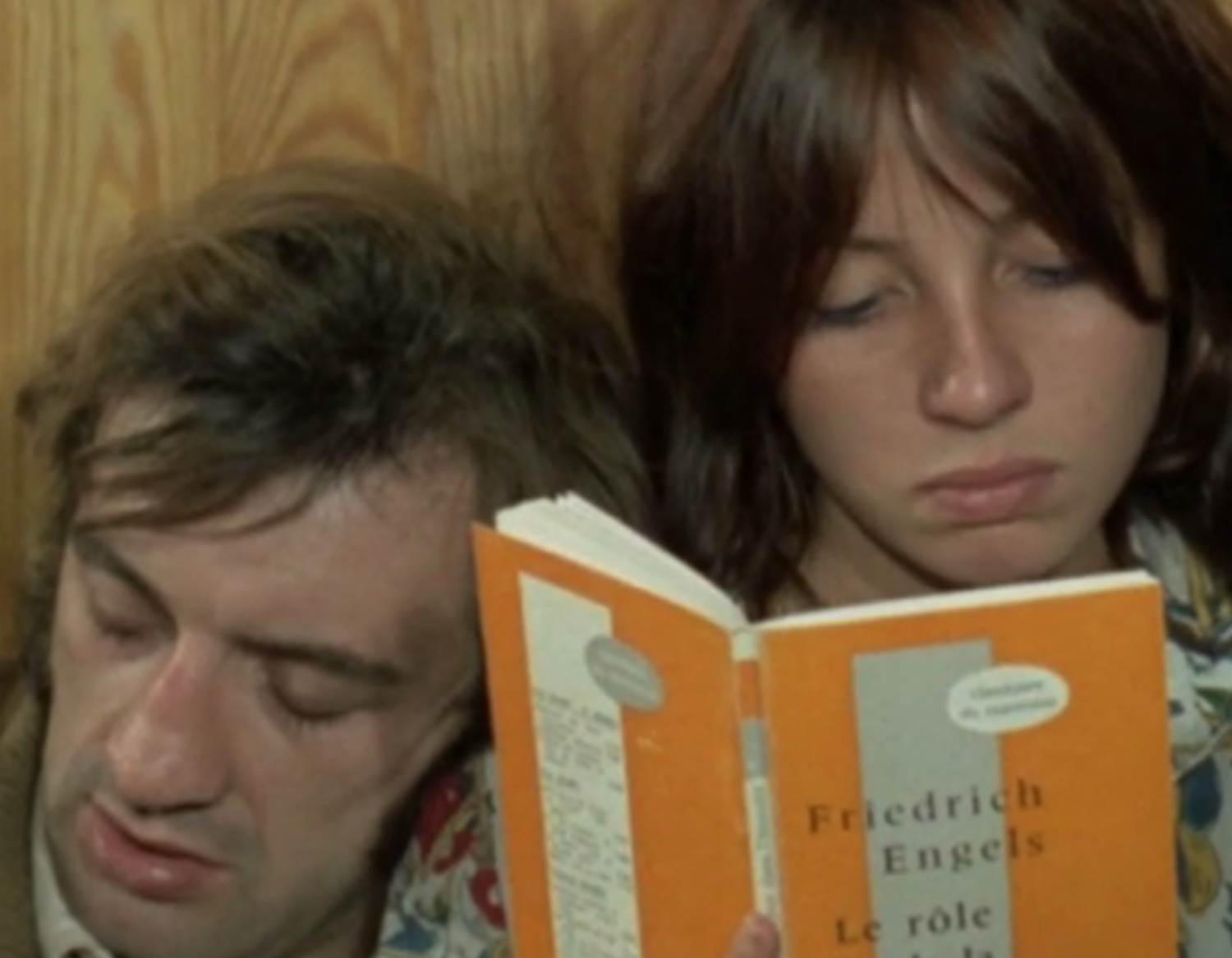

Jean-Luc Godard, the leading figure of the French New Wave from the Cahiers du cinéma faction, as opposed to the ‘Left Bank’, was an auteur and provocateur who challenged the conventions and expanded the possibilities of filmmaking. We marvel at his revolutionary ideas and innovative mise-en-scene, as well as his adorable muses, Anna Karina and Anne Wiazemsky, who radiate in every frame of his films. His extensive use of jump cuts, non-linear narratives, handheld cameras on wheelchairs, title cards, the distancing effects… created a unique film language that catapulted him to be one of the most influential filmmakers ever.

His most celebrated creative period spans seven years from Breathless to Week-End, during which he directed masterpiece after masterpiece that opened the viewers’ eyes and minds. However, he was never far from political engagement and frequently criticised the American culture, the Vietnam War, consumerism, and capitalism. His revolutionary spirit extends far beyond the medium as he threw himself into the protests of May 68, and soon became a militant and radical filmmaker. The end credits of Week-End reads ‘End of Cinema’, and marked the end to his mainstream filmmaking career, at least for a few years.

Godard's Early Short Films

Read more

Breathless

Read more

A Woman is a Woman

Read more

My Life to Live

Read more

The Little Soldier

Read more

Les Carabiniers

Read more

Contempt

Read more

Band of Outsiders

Read more

A Married Woman

Read more

Alphaville

Read more

Pierrot Le Fou

Read more

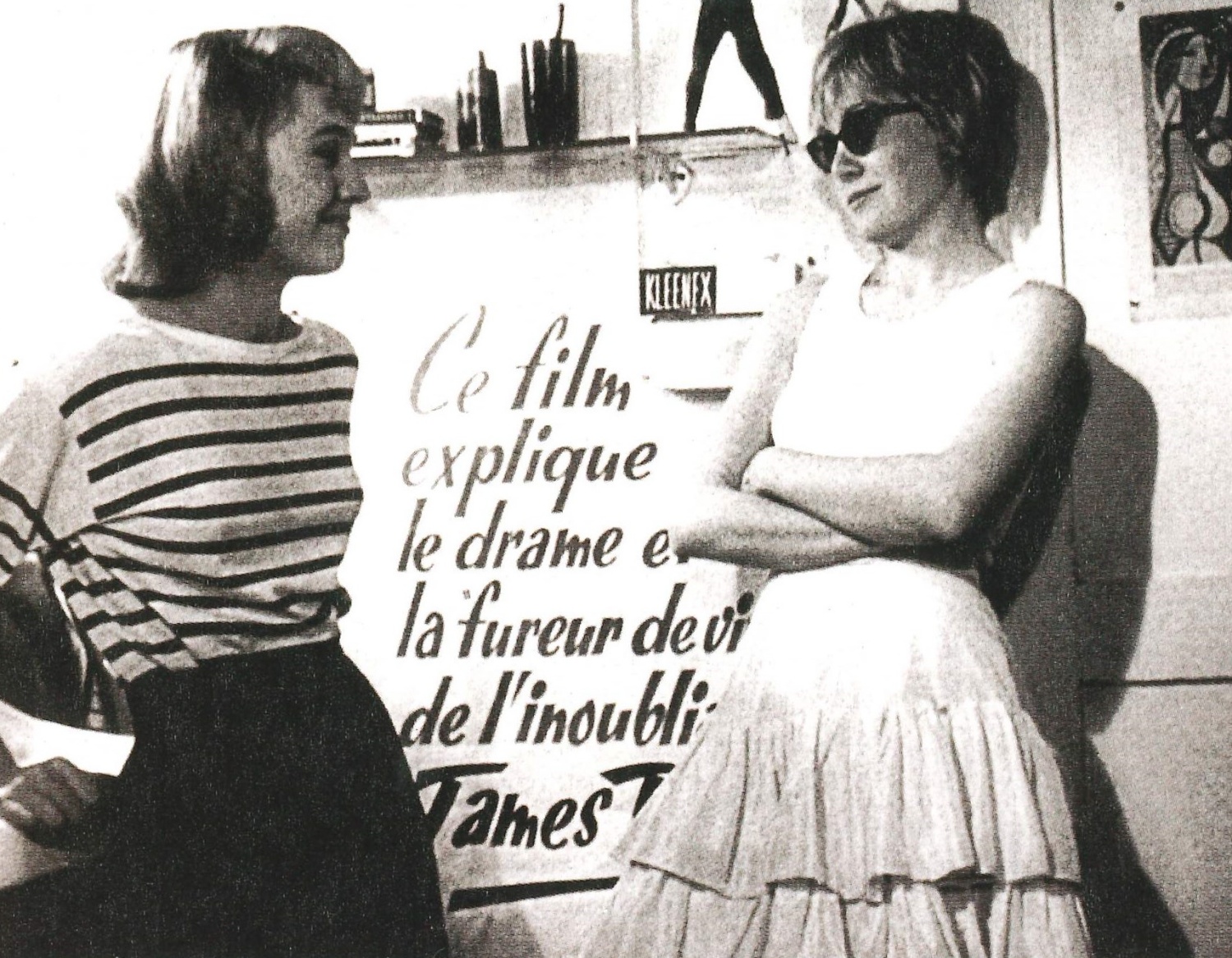

Masculine Feminine

Read more

Made in U.S.A.

Read more

2 or 3 Things I Know About Her

Read more

The Oldest Profession: Anticipation

Read more

La Chinoise

Read more

Week-End

Read more

Revolutionary Experiments

After the May 68 upheaval, Godard abandoned mainstream filmmaking because he believed that the medium was dominated [...]

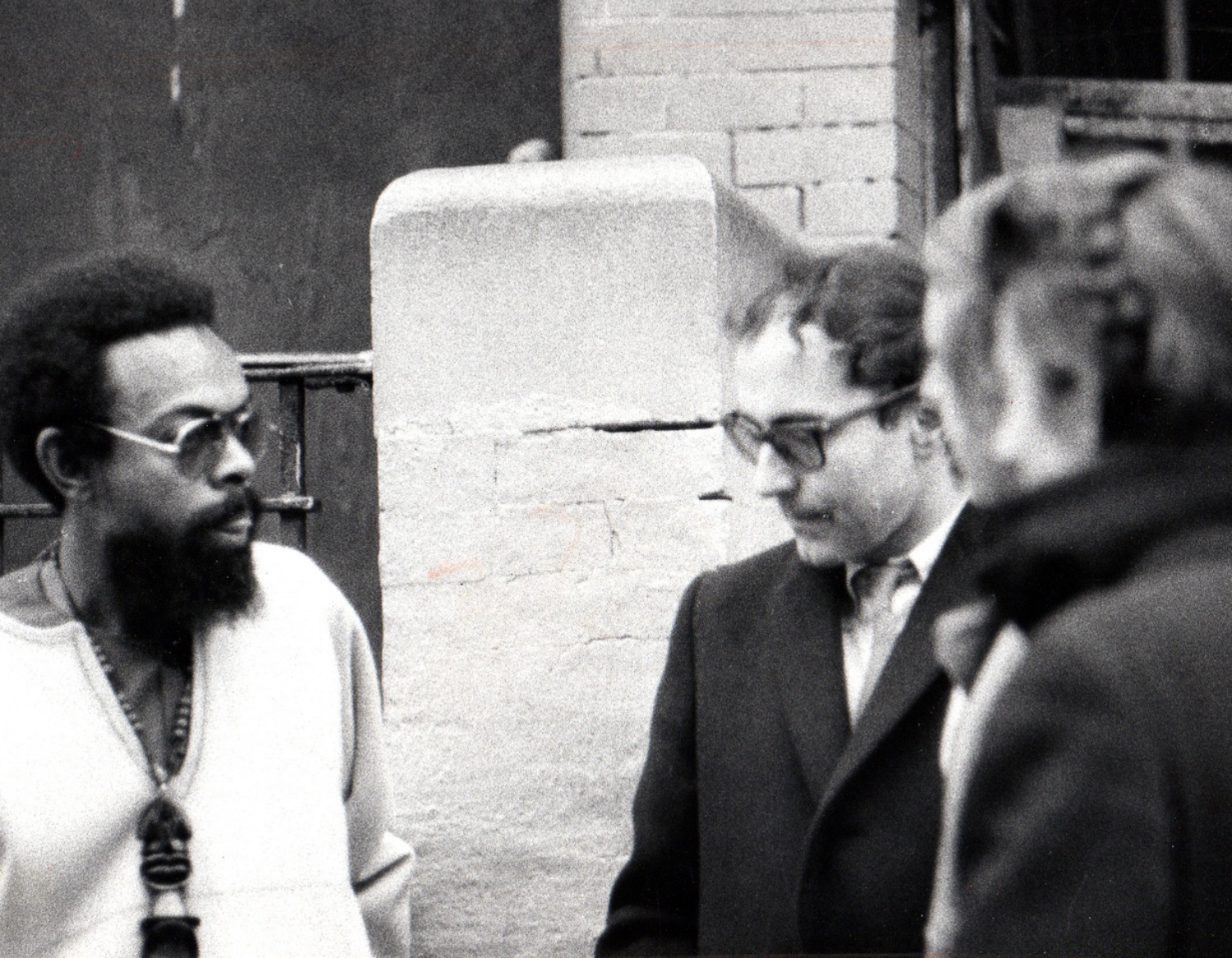

After the May 68 upheaval, Godard abandoned mainstream filmmaking because he believed that the medium was dominated by capitalists who poisoned people’s minds to serve the establ ishment. He rejected the bourgeois representation in cinema and began to employ revolutionary rhetoric to ‘make films politically’.

Like many of the fashionable French intellectuals of the time, Godard was obsessed with Maoist ideologies in the late 1960s. Thus he tried to work anonymously and formed the ‘Dziga Vertov Group’ (named after the Soviet filmmaker of Man with a Movie Camera (1929), reflecting his belief in the leftist ideologies while championing Marxism as well as Brechtian filmmaking), and founded ‘Sonimage’ company with Anne-Marie Miéville (who would later become his life partner and long-time collaborator) to make independently produced experimental films. Godard also had high hopes for television and documentaries at that time, so he began exploring the formats intensively.

Many of his films from this period were generally considered difficult and disconcerting, yet he made such wonderful films as Tout va bien, which would be the envy of many other directors. It seems to prove Godard’s famous statement: ‘cinema is truth 24 frames a second’.

One + One (a.k.a. Sympathy for the Devil)

Read more

A Film Like Any Other

Read more

The Joy of Knowledge

Read more

British Sounds (a.k.a. See You at Mao)

Read more

Pravda

Read more

Wind From the East

Read more

Struggle in Italy

Read more

One P.M. (a.k.a. One Parallel Movie)

Read more

Vladimir and Rosa

Read more

Tout va bien

Read more

Letter to Jane

Read more

Number Two

Read more

Here and Elsewhere

Read more

How is it Going?

Read more

Dialogue Between the Arts

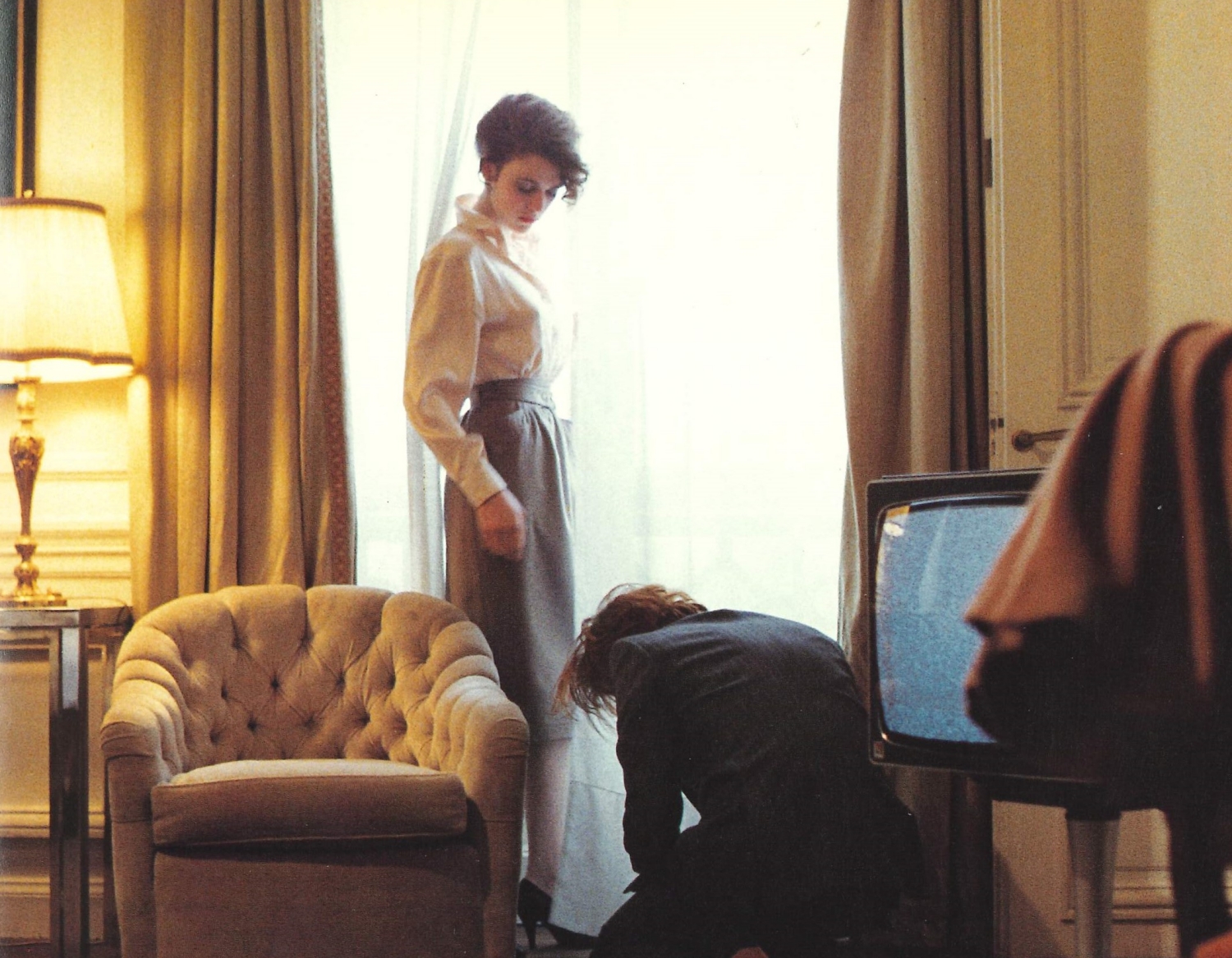

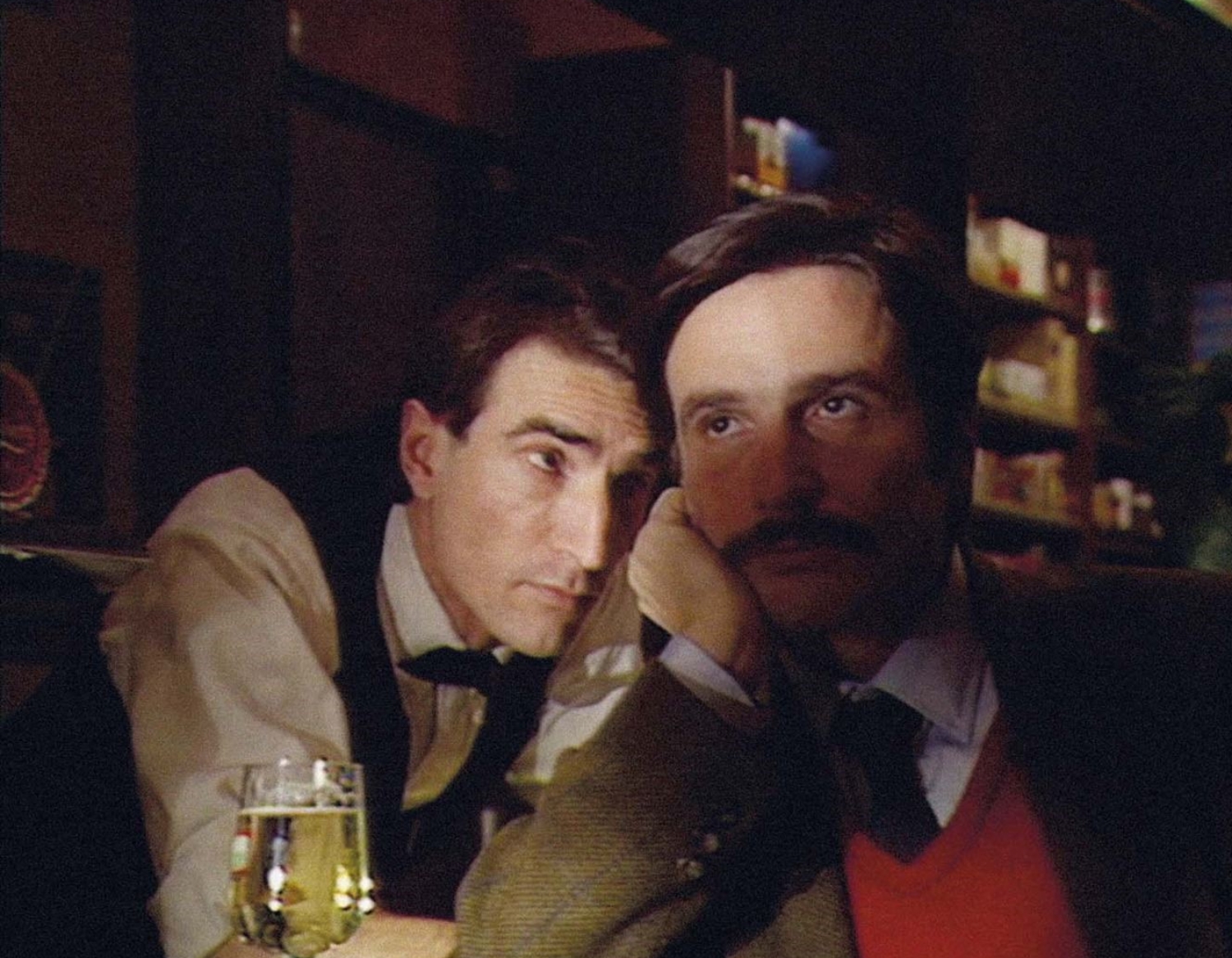

By late 1970s, Godard’s leftist utopia has become a lost paradise and the world inevitably entered into [...]

By late 1970s, Godard’s leftist utopia has become a lost paradise and the world inevitably entered into a time of late capitalism and globalisation. Godard felt the need to return to mainstream cinema, making films with stars and participating in film festivals. Though generally neglected or misunderstood, many of Godard’s second wave films are honest, sophisticated and humorous – with the narratives being more distilled and forms more abstract, and frequently starring himself as a ‘grumpy old fool’. With the burgeoning of postmodernism, most mainstream critics tended to dismiss his work as opaque and pretentious, even considered his talent exhausted.

From Every Man for Himself to Woe is Me, his use of film language is even more facile and proficient, yet no less inventive or rewarding than the lightweight, freewheeling works from his first period, although not as immediately gratifying or digestible. Nevertheless, he began to delve into intertextual analysis, putting cinema in relation to literature, painting, and music, but still managed to enrage the Catholic Church with Hail Mary, responded to the Cold War with Germany Year 90 Nine Zero, even reflected on the French New Wave in New Wave. He never ceased to experiment with film language, which gave us the impression that he could keep on innovating forever.

Every Man for Himself (a.k.a. Slow Motion)

Read more

Passion

Read more

First Name: Carmen

Read more

Hail Mary

Read more

Détective

Read more

The Rise and Fall of a Small Film Company

Read more

King Lear

Read more

Keep Your Right Up

Read more

New Wave

Read more

Germany Year 90 Nine Zero

Read more

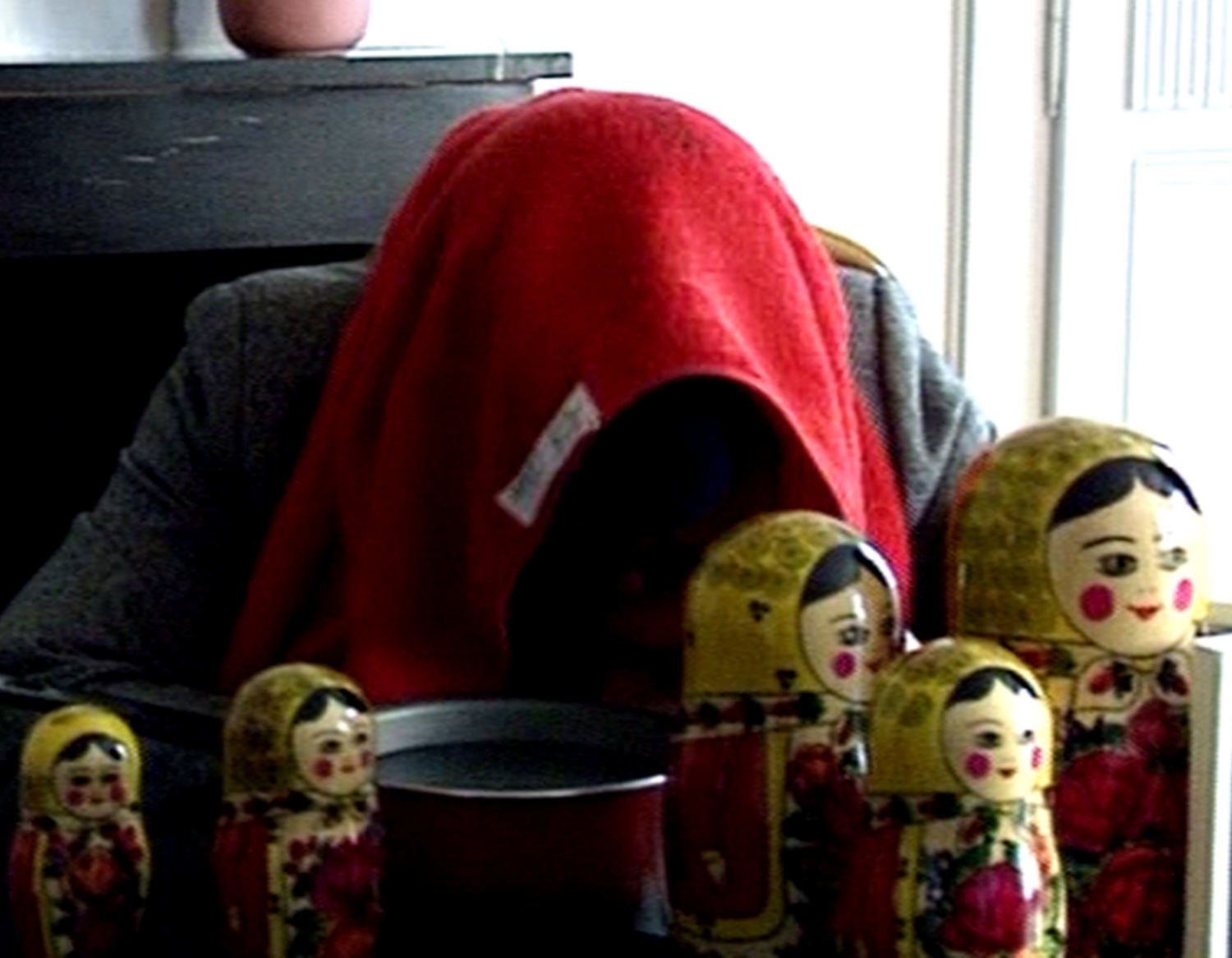

The Kids Play Russian

Read more

Woe is Me

Read more

Historical Meditations

In the final creative period of his life, Godard’s films were marked by great formal beauty and [...]

In the final creative period of his life, Godard’s films were marked by great formal beauty and a sense of requiem, especially for his personal essay JLG/JLG – Self-Portrait in December and the monumental Historie(s) of Cinema. After twenty years of unending exploration and experimentation, Godard has found the most satisfying way of expression through stunningly beautiful imagery and deeply compassionate cinematic essays, that is at once intellectual and lyrical. His use of montage and superimposition liberates ideas and feelings into a form of cinematic poem. If ever there were films made with the stream of consciousness, Godard has demonstrated how it is done.

In Film Socialism, Godard has completely deconstructed and reflected on the political ideology that he abided by throughout his entire life; when the whole world was obsessed with 3D movies, Godard experimented with 3x3D and Goodbye to Language his homemade 3D cameras, to explore the true cinematic language that technology can provide without resorting to cheap thrills or mass entertainment. As the ultimate cinematic auteur, Godard kept on putting into practice how a true artist can expand and live through (cinema) history until the very end.

JLG/JLG - Self-Portrait in December

Read more

2x50 Years of French Cinema

Read more

For Ever Mozart

Read more

Chosen Moments of Historie(s) of Cinema

Read more

In Praise of Love

Read more

Our Music

Read more

Film Socialism

Read more

Goodbye to Language 3D

Read more

The Image Book

Read more

After the Reconciliation

Read more