2024

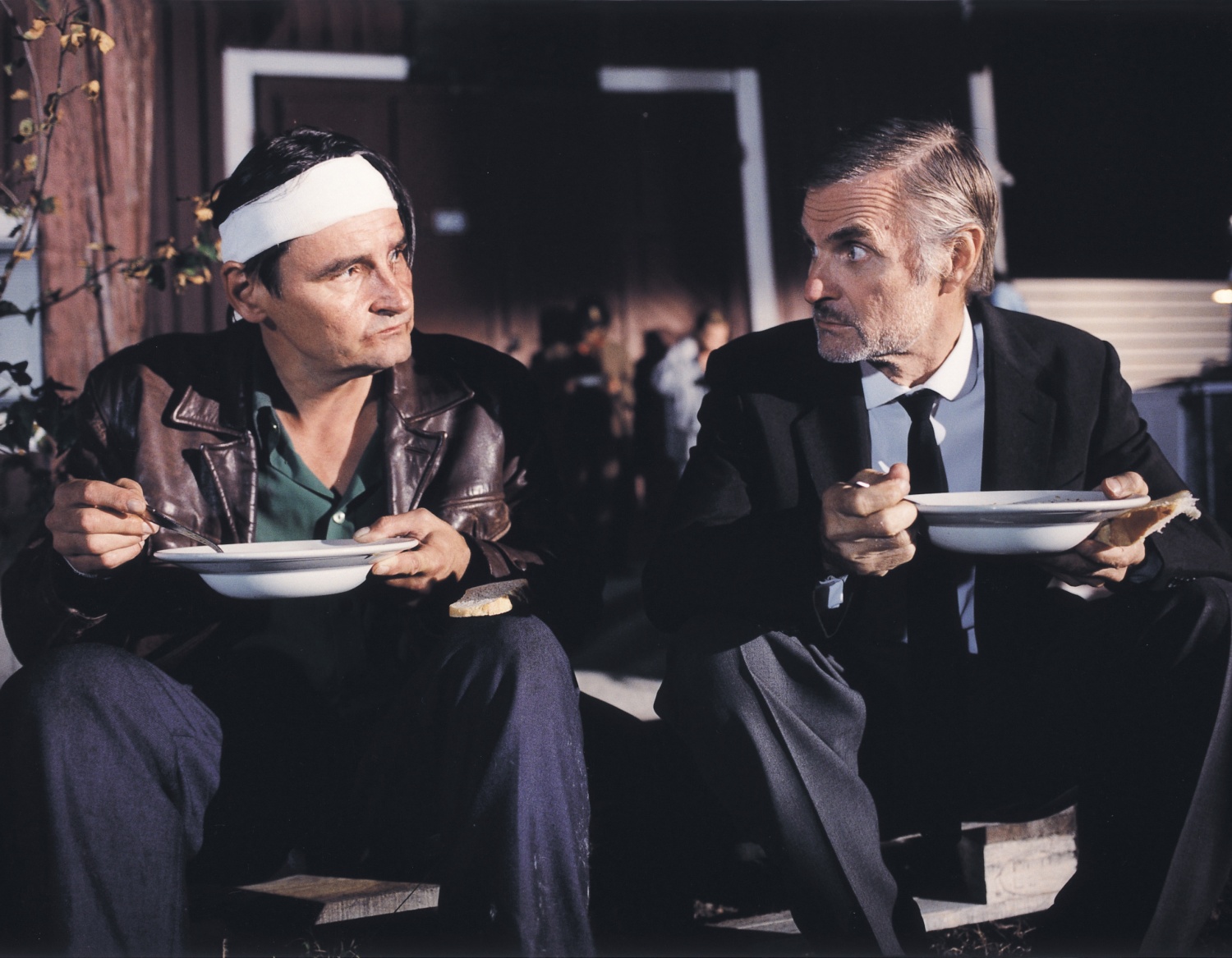

The Other Side of Comedy – The Films of Aki Kaurismäki

All tickets for screenings at Broadway Cinematheque are available at its venue and website only.

Aki Kaurismäki [...]

All tickets for screenings at Broadway Cinematheque are available at its venue and website only.

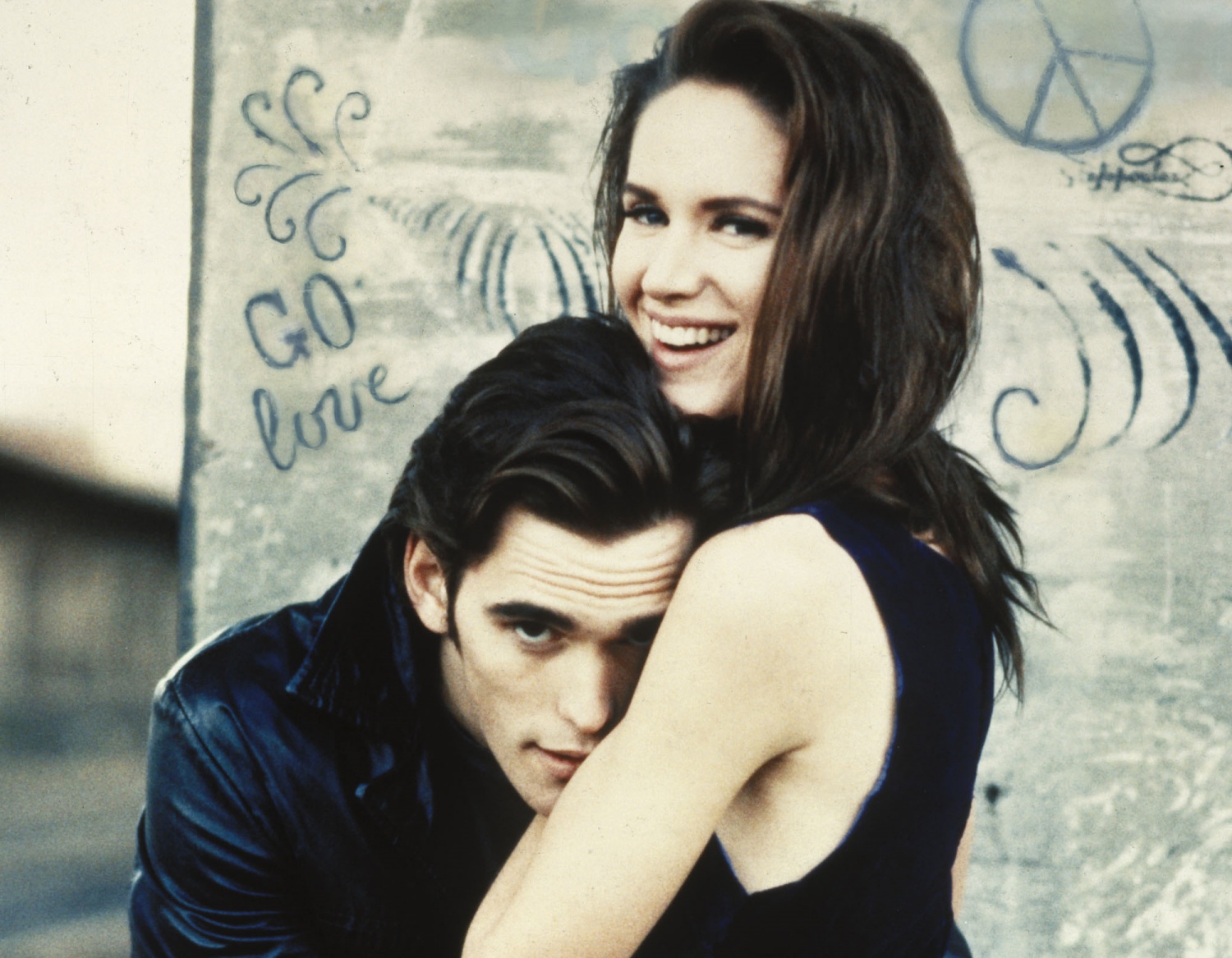

Aki Kaurismäki thinks his own films are dreadful. And his deadpan comedies are grim. But the bleaker the director has become, the more tender his films. No matter how despairing the reality is, his underdog characters always find solace in a sleazy bar, in eccentric rock 'n' roll, and in the company of a devoted canine friend.

Combining the restraint of Robert Bresson with the surrealism of Luis Buñuel, the profound Finn cinephile creates his own cinematic universe of visual stylisation and mordant jokiness for his humane comedy. Highly distinctive but hard to define, Aki’s compositions are simple yet subtly expressive; his approach skews towards a tradition of neorealism, yet flecked with fairytalelike fantasy; his ambiance is nostalgic, yet evoking a modernist vibe. With witty irreverence and stylish intelligence, the artist works dichotomy into an arresting sensibility, championing humanity and spontaneous solidarity while sliding out an unspoken critique towards modern alienation and social injustice.

Imbued with the melancholy lyricism of Edward Hopper, Aki furnishes the humble homes and working spaces with Scandinavian minimalism and a colour palette at once muted and vibrant, where the loneliness of the working class collides with bittersweet tenderness. Retro radios, vintage Cadillacs, and local bands all conspire to tell stories about beautiful losers and bring out a full range of their shrouded but piercing emotions, transforming into his idiosyncratic motifs that emulate the red kettle of his revered Ozu Yasujiro.

vulnerabilities with a weird charm of dry and deadpan humour. Surviving on the margins, his reclusive working-class heroes persevere, trying to walk tall in a world of prejudice, and rebuild their lives against everyday adversity. Hidden behind their poker faces and understated dialogues are existential frustration, alongside suppressed emotions and desires. Whatever fate throws at them, Aki always finds in his heart to reward them with a glimpse of hope – and love – at the end. Comedy rarely comes so bleak, depression is rarely so funny, and miracles are rarely so real.

‘When all hope is gone, there is no reason for pessimism.’ If you can’t cry, why not laugh?

Co-organiser:

Special Thanks:

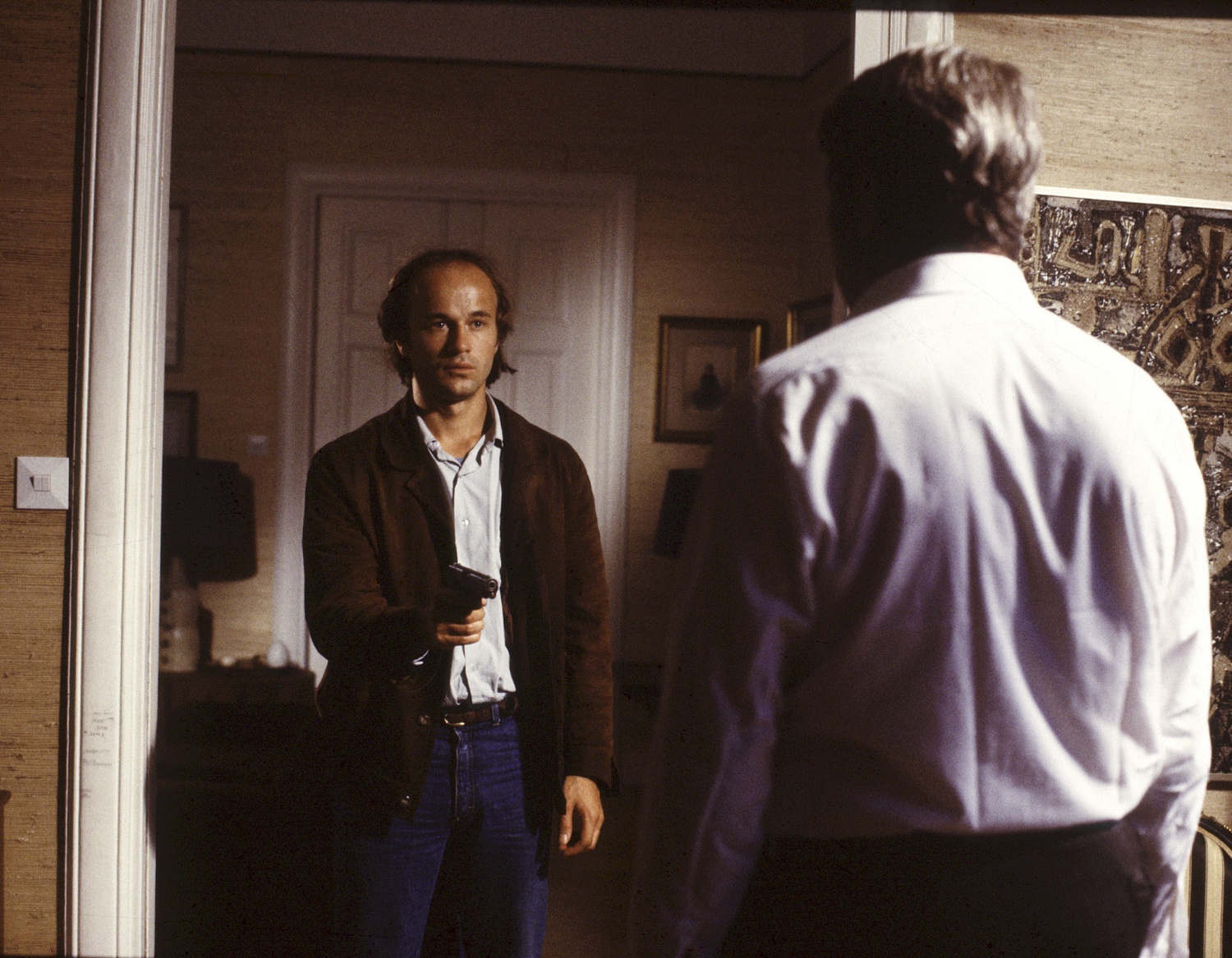

Crime and Punishment

Read more

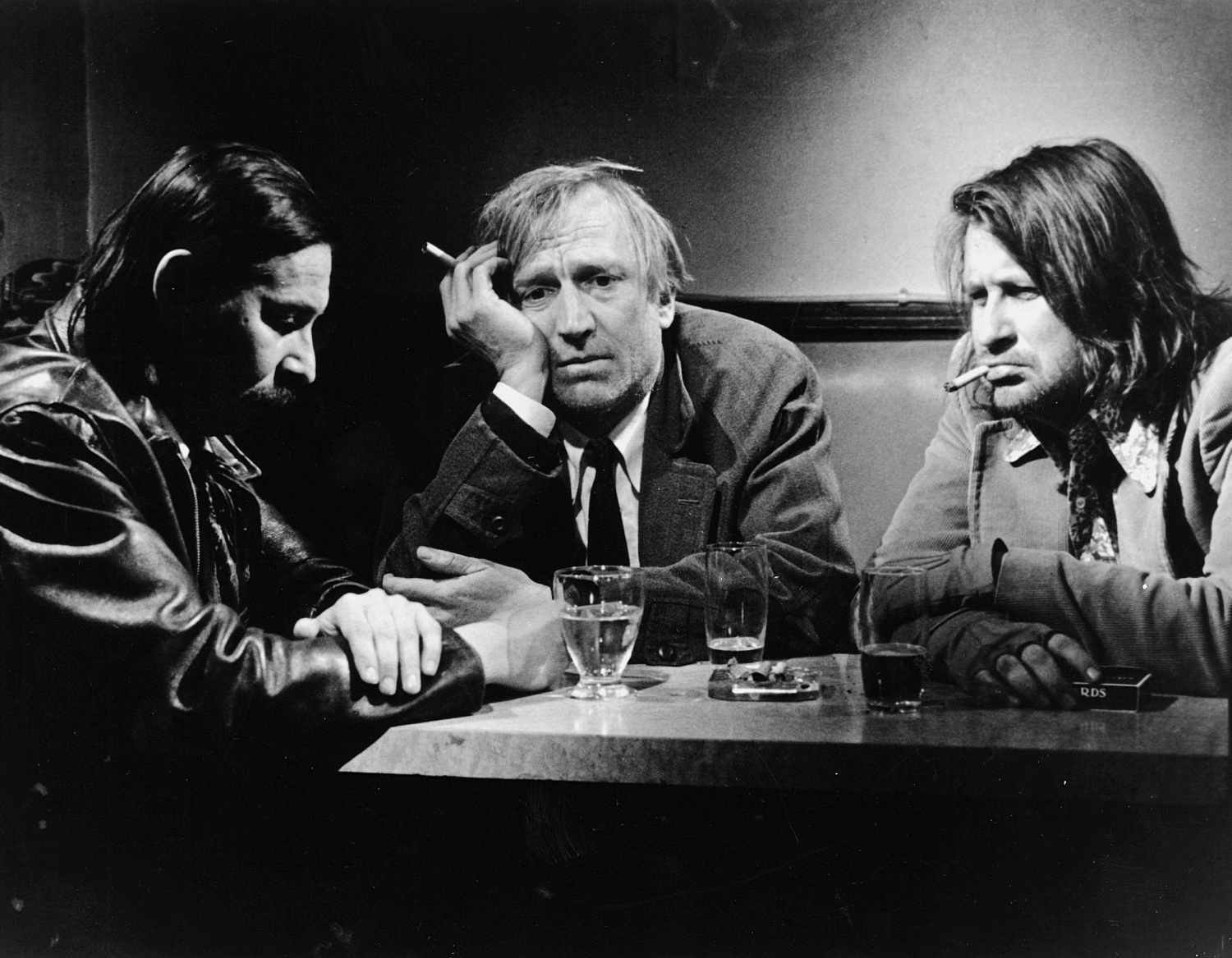

Calamari Union

Read more

Shadows in Paradise

Read more

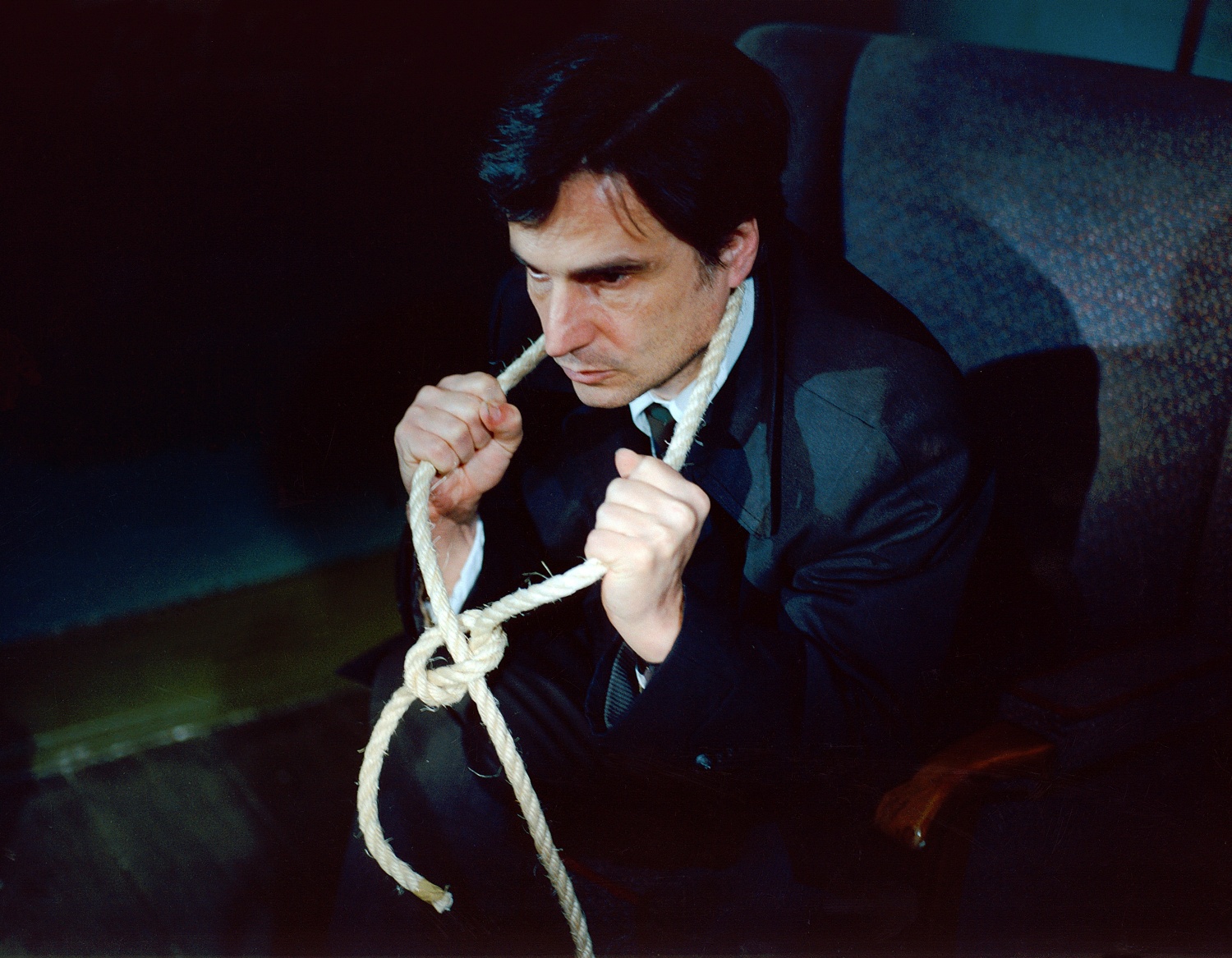

Ariel

Read more

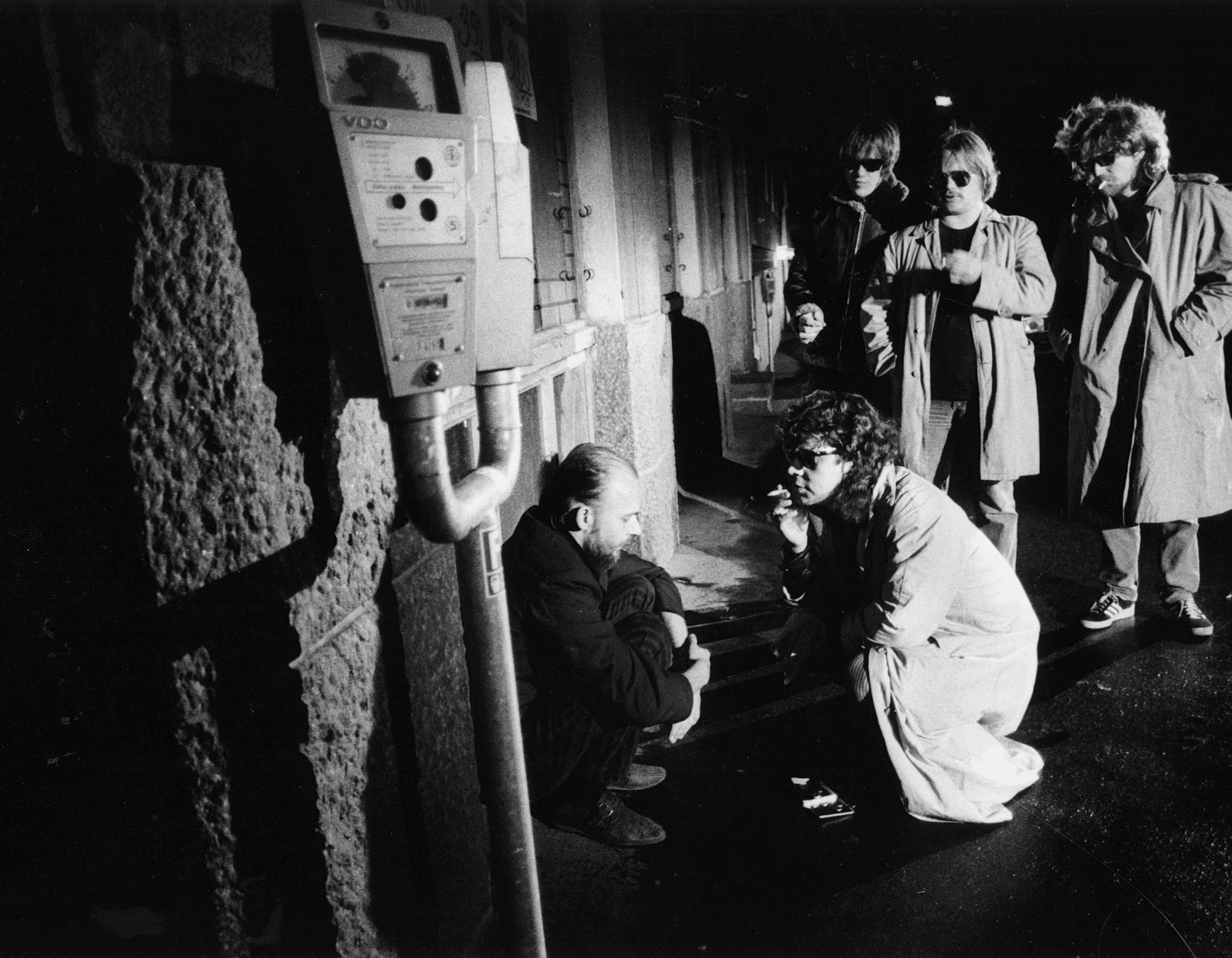

Leningrad Cowboys Go America

Read more

I Hired a Contract Killer

Read more

La Vie de Bohème

Read more

Take Care of Your Scarf, Tatiana

Read more

Drifting Clouds

Read more

Juha

Read more

The Man Without a Past

Read more

Lights in the Dusk

Read more

Le Havre

Read more

The Other Side of Hope

Read more

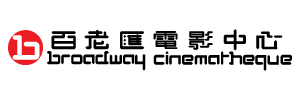

Seeing the Unseen Godfrey Reggio’s The Qatsi Trilogy

In his Qatsi (= life) Trilogy, former Catholic monk and artist-cum-activist Godfrey Reggio’s critique of technology is [...]

In his Qatsi (= life) Trilogy, former Catholic monk and artist-cum-activist Godfrey Reggio’s critique of technology is not a message, but manifests as cinematic method in the form of non-fiction and wordless, visual narrative. Between poetry and discourse, and via torrents of images transported through Philip Glass’ music, cinema becomes, in Reggio’s own terms, a ‘sacrament’ directly confronting the technicised human world by firing it up.

In his unique universe, images of nature, urbanity, human conditions, space technology, militarism and consumer culture all share the same image space nonhierarchically, articulating what Reggio describes as the ‘unity imperatives’ of technological society. They blend into one another and juxtapose without any plot function. The world is like a new organism – breathlessly pulsating, horizonless, and as real as it is virtual. An image may hiss, scream, stagger, dash off, blink, swerve and swirl – that’s all cinema doing it. Slow motion, reverse backward play, time-lapse, superimposition, computer-graphics, synthetic images, found footage, augmented vision and more are all at Reggio’s free disposal, without symbolic burden, and stripped of conventional usage.

To Reggio, the celluloid film is about the negative becoming the positive; and negation is a way to resist destiny, to bring about change by learning to feel strange for what has become routine. Cinema and imagemaking would remain that liminal space to uphold perceptual estrangement, and camera presence, from within or outside our planet, to make concrete and visible the unseen.

Psychedelia – Cinema as a Fever Dream

‘One pill makes you smaller, and one pill makes you small. And the ones that mother gives you don’t do anything at all...’

Made popular by the widespread use of psychedelic substance among young people during the counterculture movement of the 60s and 70s, psychedelic cinema emerged as part of the artistic revolution involving music, art, literature and philosophy.

Psychedelic, which literally means ‘mind-manifesting,’ can just be applied to an aesthetic style or an affective-sensorial influence, conjuring an altered state of subjective reality and hallucinogenic experiences that reflect the revelation of our mind. Blurring the lines between dream and reality, these films often use visual images or unconventional narrative techniques to alter the viewers' sense of spatiotemporal perception.

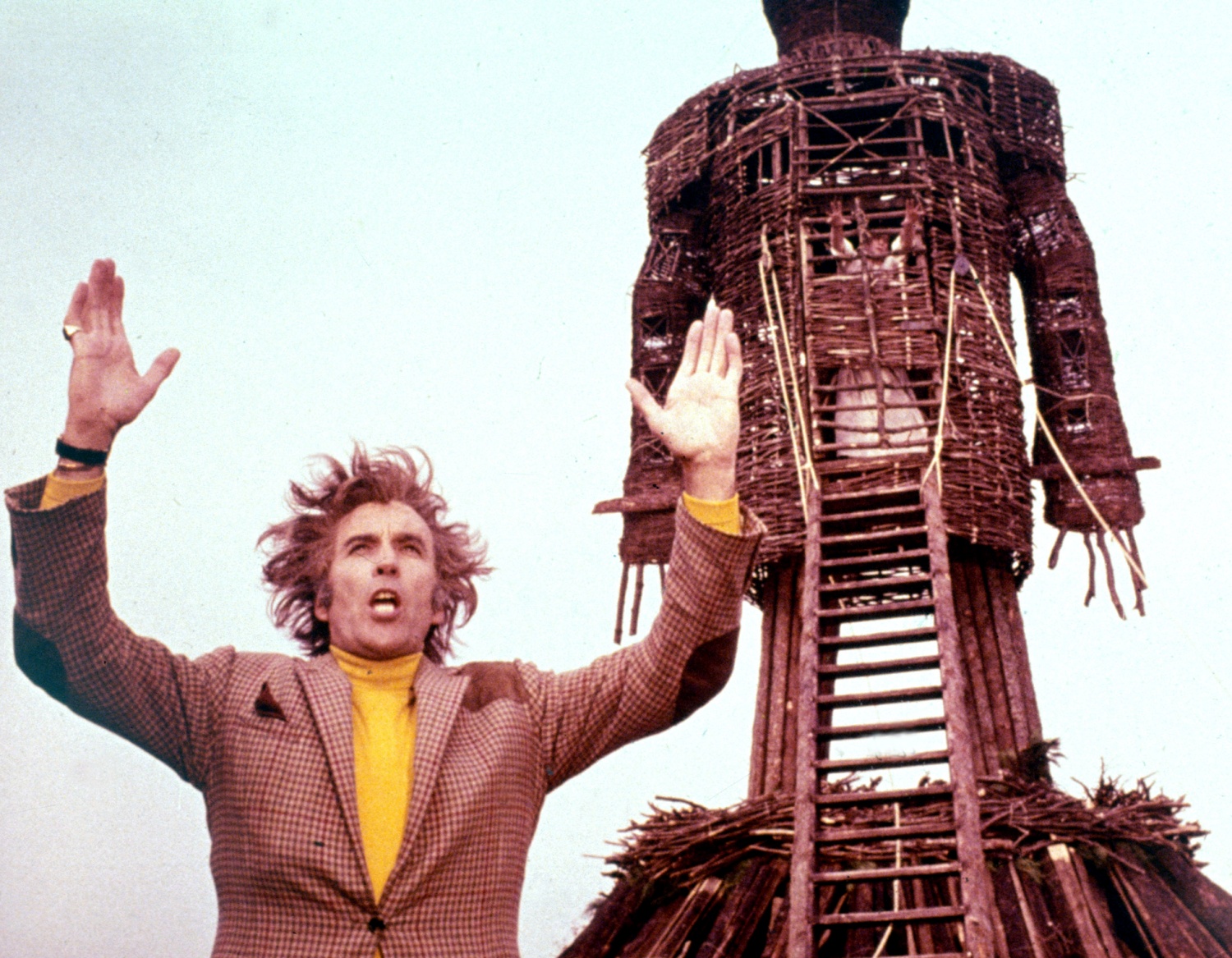

Dennis Hopper’s 1969 Easy Rider, one of America’s first counterculture films that fused mainstream aesthetics with avant-garde tendencies to capture the sociopolitical climate of the time, helped bring psychedelic films into Hollywood. Robert Altman’s surreal, dreamlike reality in 3 Women, Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg’s dizzying experiment in Performance, and Hayashi Kaizo’s grafting of silent era aesthetics in To Sleep So as to Dream - all see the artists explore the interplay of films and drug induced states of mind as mutually constitutive transformations in human consciousness – and also cinematic adventures.

Some psychedelic films are full-on assault on the senses, pushing your mental state to the edge. Recreating an out-of-body experience fuelled by psychedelic drugs, provocateur Gaspar Noé conceives a transcendental odyssey that defies life and death with masterful aerial shots in Enter the Void. Ken Russell creates a bombastic take on the pop opera genre with Tommy, a relentlessly frenetic musical experience with jaw-dropping visual imagination.

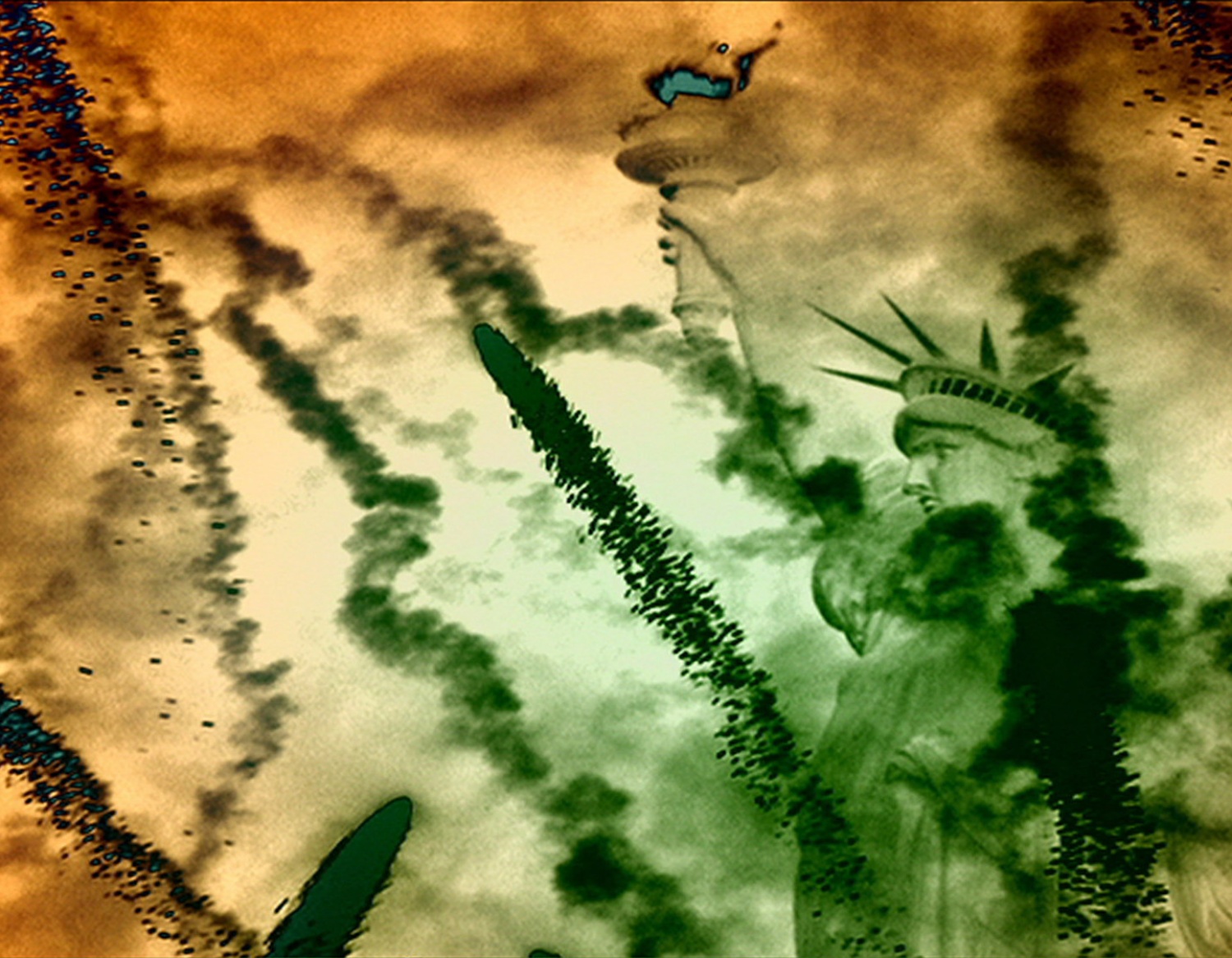

But perhaps there is no experience like a drug-addled mind in terror. The Wicker Man sees director Robin Hardy combine incredibly creepy behaviours, eerie folk music and the mainstream fear of exotic religions into a trailblazing folk horror genre. In Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, a terrifying depiction of a drug-fuelled crime spree is followed by even more horrible depiction of state-sanctioned mind-control that sear into your brain forever.

As Jefferson Airplane’s Grace Slick sings in the band’s Alice in Wonderland -inspired psychedelic anthem ‘White Rabbit’: ‘Remember what the dormouse said, feed your head.’