2024

The Perfect Duo – The Films of Powell and Pressburger

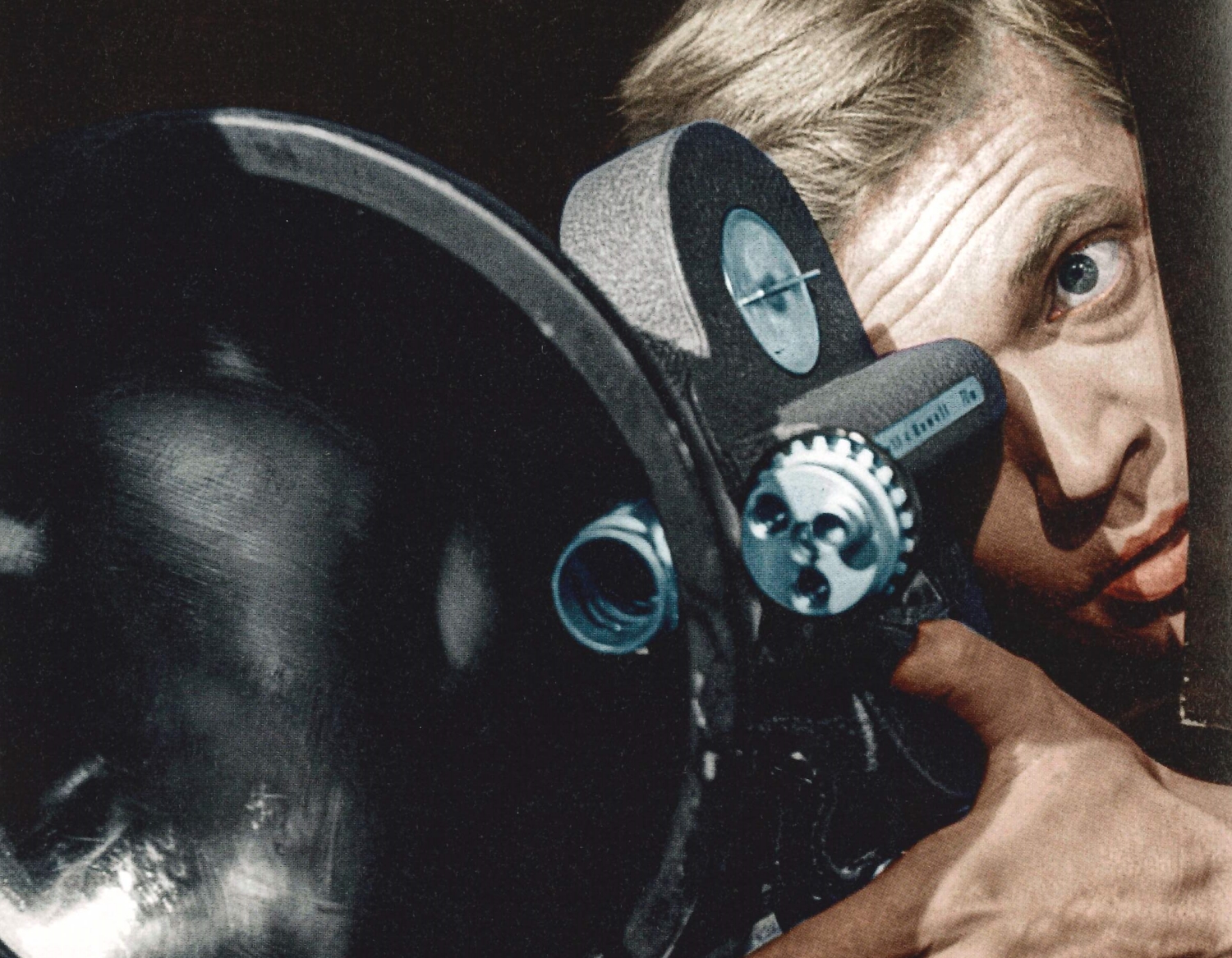

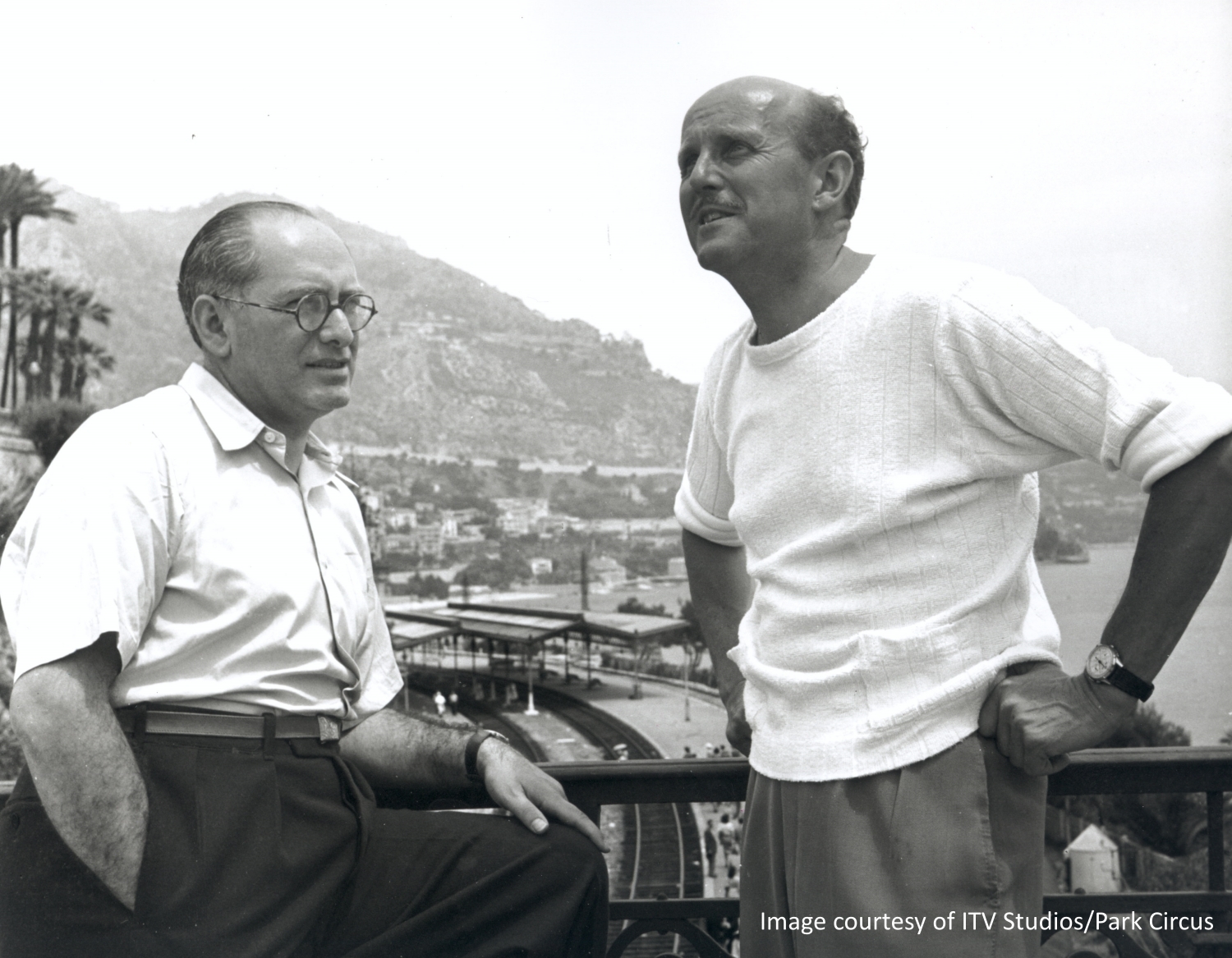

Art is life – a motto that rings in The Red Shoes, apparently reflects the philosophy of Michael Powell (1905-90) and Emeric Pressburger (1902-88) towards filmmaking. Almost like a morbid obsession, their total devotion to the cinema underscores the phenomenal power and mystery of their original, diverse body of work, at once daringly subversive, aesthetically inventive and ravishingly beautiful. Few can rival their cultural legacy and enduring influence in British film history.

Working hand in hand since the outbreak of World War II, the coalescence between English native Powell and Hungarian émigré Pressburger ‘proved to be one of those fortuitous combinations where the chemistry was felicitous in every degree’ (film historian William K. Everson). Powell’s dynamic direction was given substance by Pressburger’s richly layered and incisive screenplays; their distinct cultures and personalities converge on the common ground of an uncompromising take on filmmaking. The two cinematic visionaries and innovators shared credits as writers, directors and producers under the banner of their production company The Archers – a hallmark that denotes an integral artistic partnership.

Their early collaborations hit the stride with a series of wartime thrillers. Surpassing the boundaries of a propaganda film, the creative duo delves into humanity, contemplating friendship, romance, desire and belief while denouncing the wars. Grounded in reality yet embracing surrealism, their films evoke magical, dreamlike fantasy that celebrates the transcendent value of love – through three incarnations of an ideal woman embodying the heart and soul, or an adjudication in the heavenly tribunal for a presumed dead soldier returning to his love on Earth. Bold and revolutionary, they crafted films that explore the possibilities of cinematic language, and the mesmerising power of chiaroscuro and colour, unveiling covert depression in stark monochrome, while exposing burning desires in the feverish red of Technicolor.

Psychedelia of their unbridled imagination is in full manifestation under the immaculate direction, powered by exceptional cinematography, sound, lighting, and production design. The stairway to heaven, the bell tower on a cliff, and a boat in a whirlpool – all these visual splendours that bring to life the indecipherable psyche are made up by awe-inspiring special effects. The fusion of theatrical and cinematic magic, the wedding of sound and image in ‘composed cinema’, and their stylised artistic experimentation resulted in a tour de force of whimsical fantasy – a universe of cinema inventiveness that never existed before.

A devotee of The Archers, Martin Scorsese acknowledged in Made in England: The Films of Powell and Pressburger that their body of work is a constant source of energy, and a reminder of what life and art are all about. That’s exactly what Powell and Pressburger’s visionary cinema was – and still is.

The Spy in Black (a.k.a. U-Boat 29)

Read more

49th Parallel

Read more

The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp

Read more

A Canterbury Tale

Read more

I Know Where I’m Going!

Read more

A Matter of Life and Death (a.k.a. Stairway to Heaven)

Read more

Black Narcissus

Read more

The Red Shoes

Read more

The Small Back Room (a.k.a. Hour of Glory)

Read more

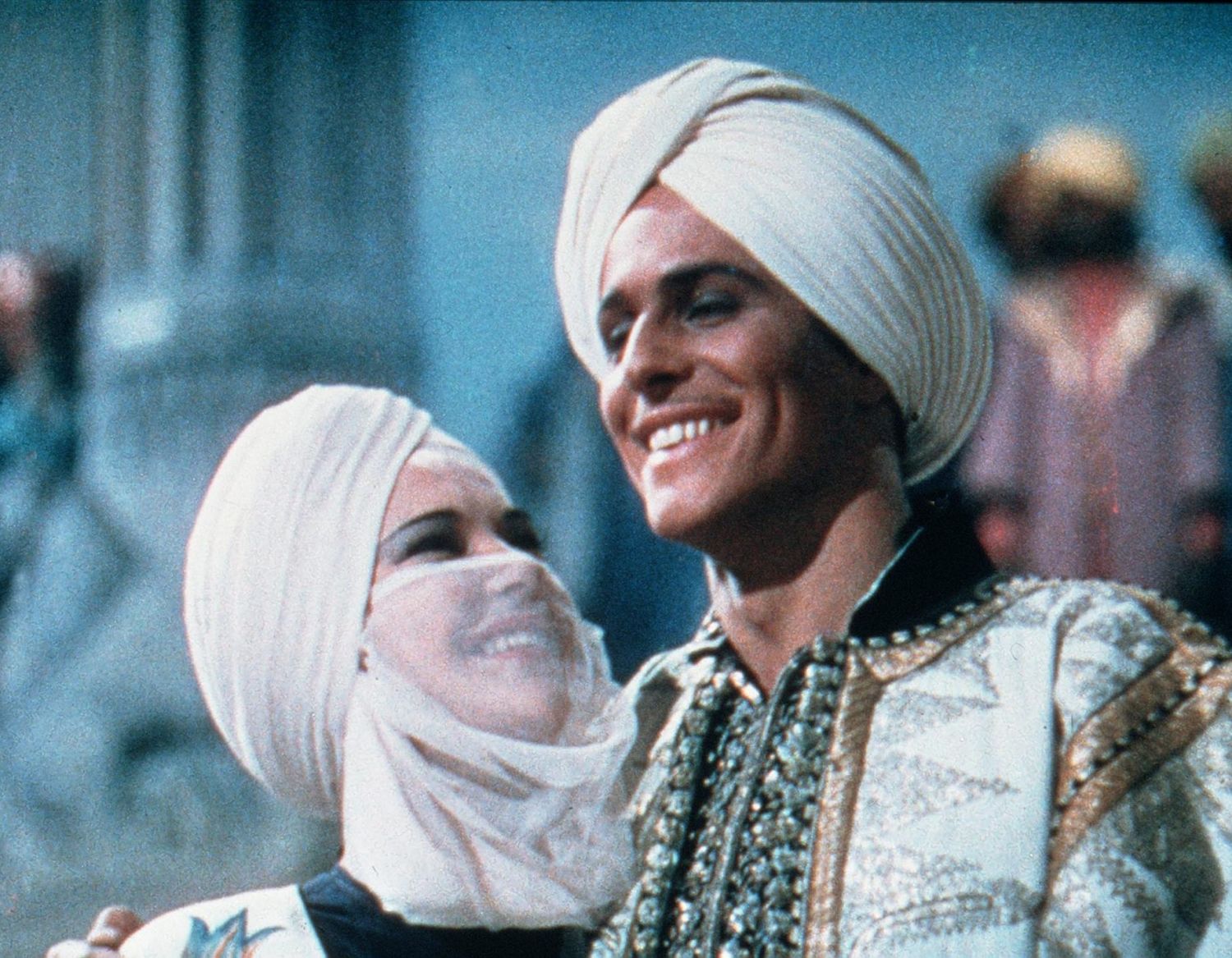

The Tales of Hoffmann

Read more

Made in England: The Films of Powell and Pressburger

Read more

Cinema Heritage: From The Film Foundation

The Golden Age

Restored Classics

Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet: A Poetic Political Engagement

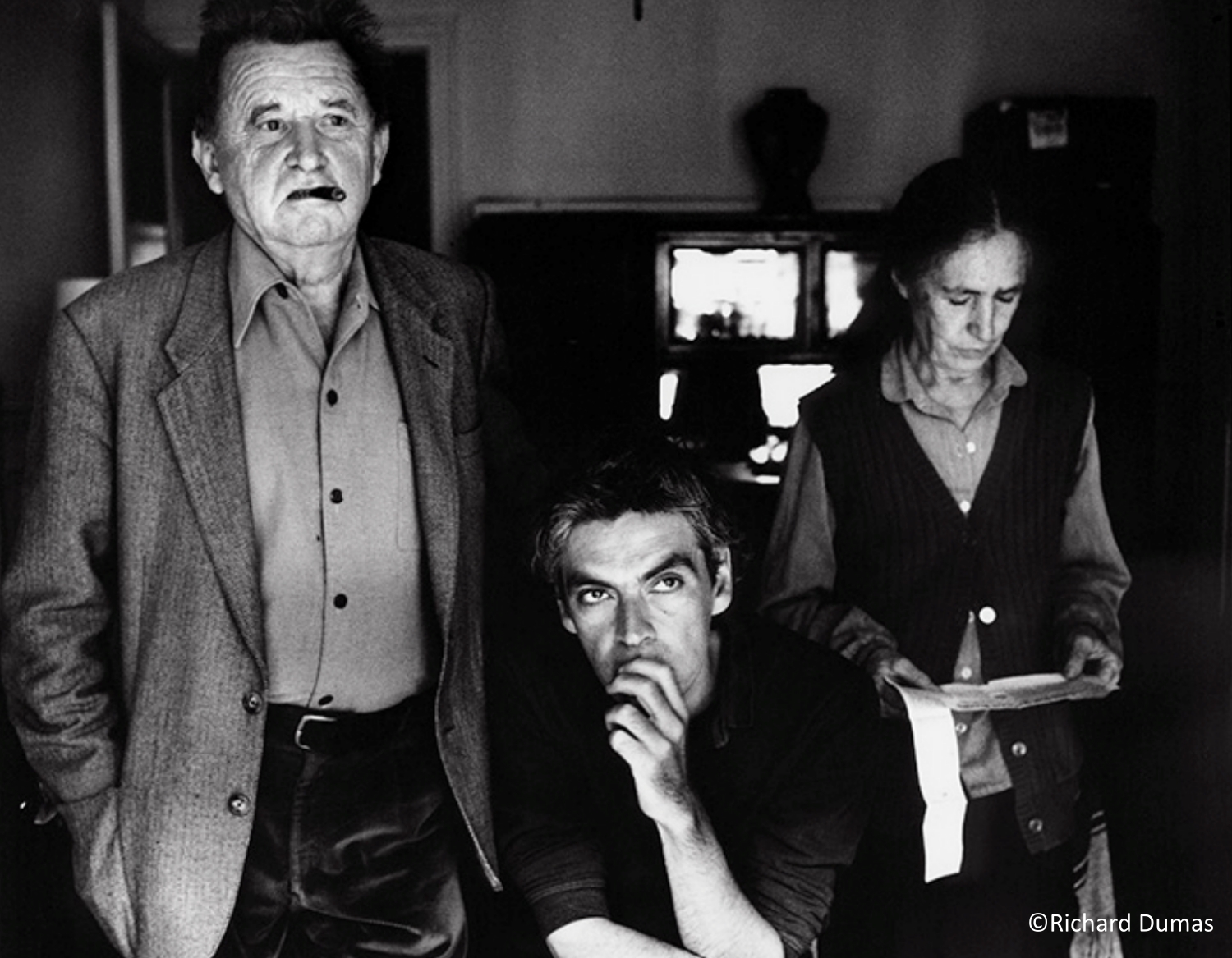

Danièle Huillet (1936-2006) once recalled that she could clearly remember first meeting Jean-Marie Straub (1933-2022) in Paris [...]

Danièle Huillet (1936-2006) once recalled that she could clearly remember first meeting Jean-Marie Straub (1933-2022) in Paris in November 1954 because the Algerian War had just broken out. Not long after, as they began work on a script for a film about the life of Bach, their relationship was again marked by the conflict when the couple left France in 1958 so Straub could avoid the draft.

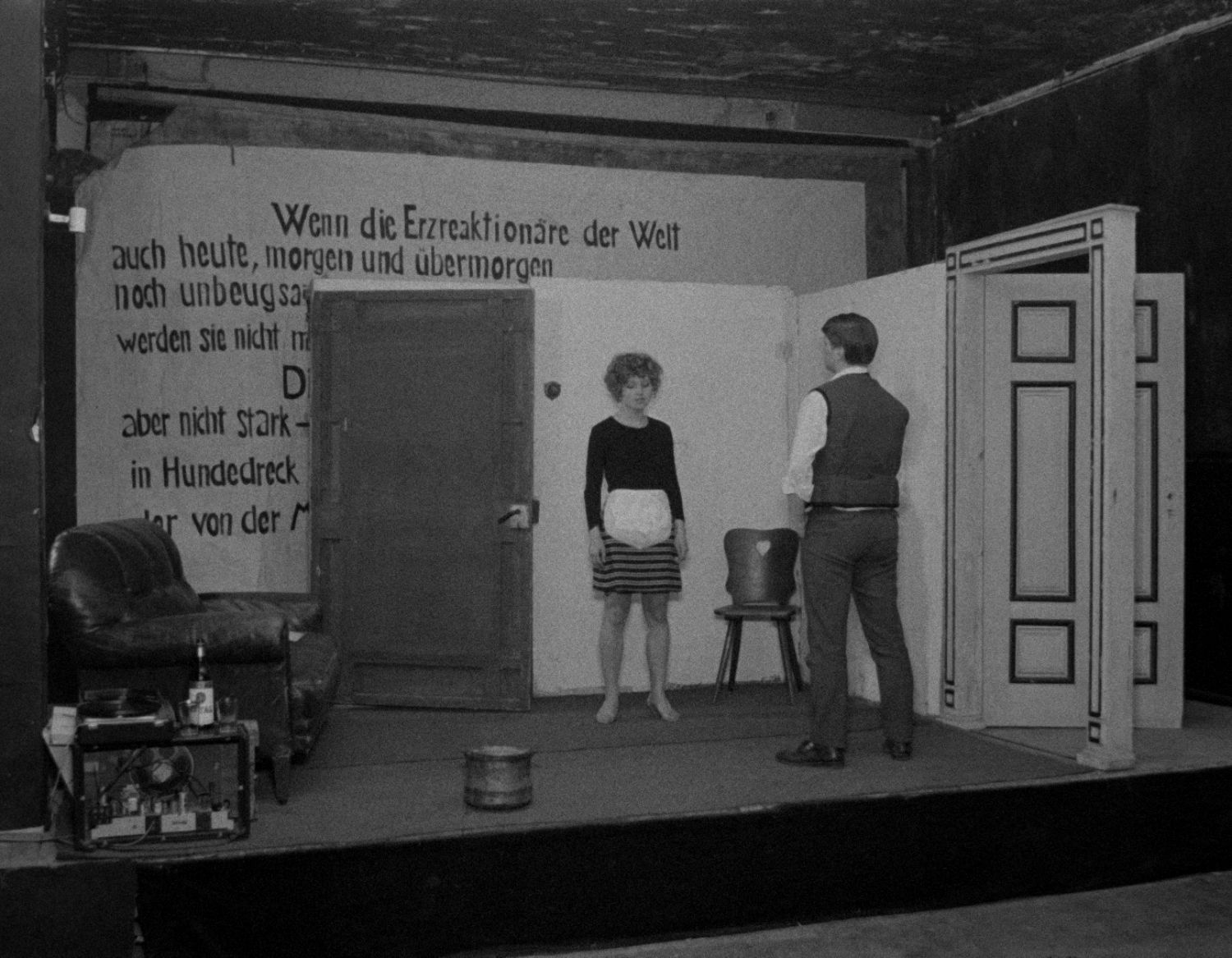

They settled in Munich, home to a lively, young film scene, making their first films in German: Machorka-Muff, Not Reconciled and the long-planned The Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach, that garnered them a small but enthusiastic critical reputation. Settling in Rome in 1969, they became truly international filmmakers, making films with crews and casts in Germany, Italy, France, Egypt and (three shots) America.

Compared early on to the work of Robert Bresson and Bertolt Brecht, their films are, nevertheless, truly singular. Disorienting yet overwhelming, these films stare at, and listen intensely to, the world and its people, so that we may see what is always present but absent. Filmed by a camera Straub once described as an ‘accomplice,’ the characters energetically burst off screen through carefully rehearsed performances that focus on the voice and minimal, but immense, gestures. We experience their struggles, their hopes, and their pain as though they were sitting right in front of us.

With simple means, they produced films that are diverse, polished and handmade. They collaborated with many of the same crew members for decades and edited their films themselves, creating unexpected, off-kilter rhythms out of blocks of shots (‘cinematographic material,’ they called it) with direct location sound that was never mixed to smooth out the discontinuity between takes.

Just as contemporary politics and border crossing marked their lives early, their later films return to the themes of geography and language: in short, the land. Throughout the 1970s, land gains an ever more prominent role in films such as Moses and Aaron and From the Cloud to the Resistance and see how it looks today and what lies hidden beneath it. In Class Relations, as if seen in a nightmare, it is the nocturnal landscapes the protagonist must cross as he explores America, while in Sicilia!, the filmmakers visually link conversations around earthy topics like food and desire to panning or tracking shots of Sicily’s dry lunar countryside.

Faster than Godard (to paraphrase Pedro Costa, who made the magical and stimulating documentary about Straub-Huillet’s editing process), these films often leave one breathless and off balance upon a first viewing. But that is just what can happen when one tries to capture the world, pertinent to their favorite painter Paul Cézanne once stated: ‘The immensity, the torrent of the world in a tiny piece of material.’

– Ted Fendt, editor of Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet (FilmmuseumSynemaPublications, 2016)