2024

OPENING FILM

CLOSING FILM

FESTIVAL SPOTLIGHT

The Second Act

Read more

Wild Diamond

Read more

Another End

Read more

The Devil's Bath

Read more

Foreign Tongue

Read more

Desert of Namibia

Read more

My Favourite Cake

Read more

Elementary

Read more

No Other Land

Read more

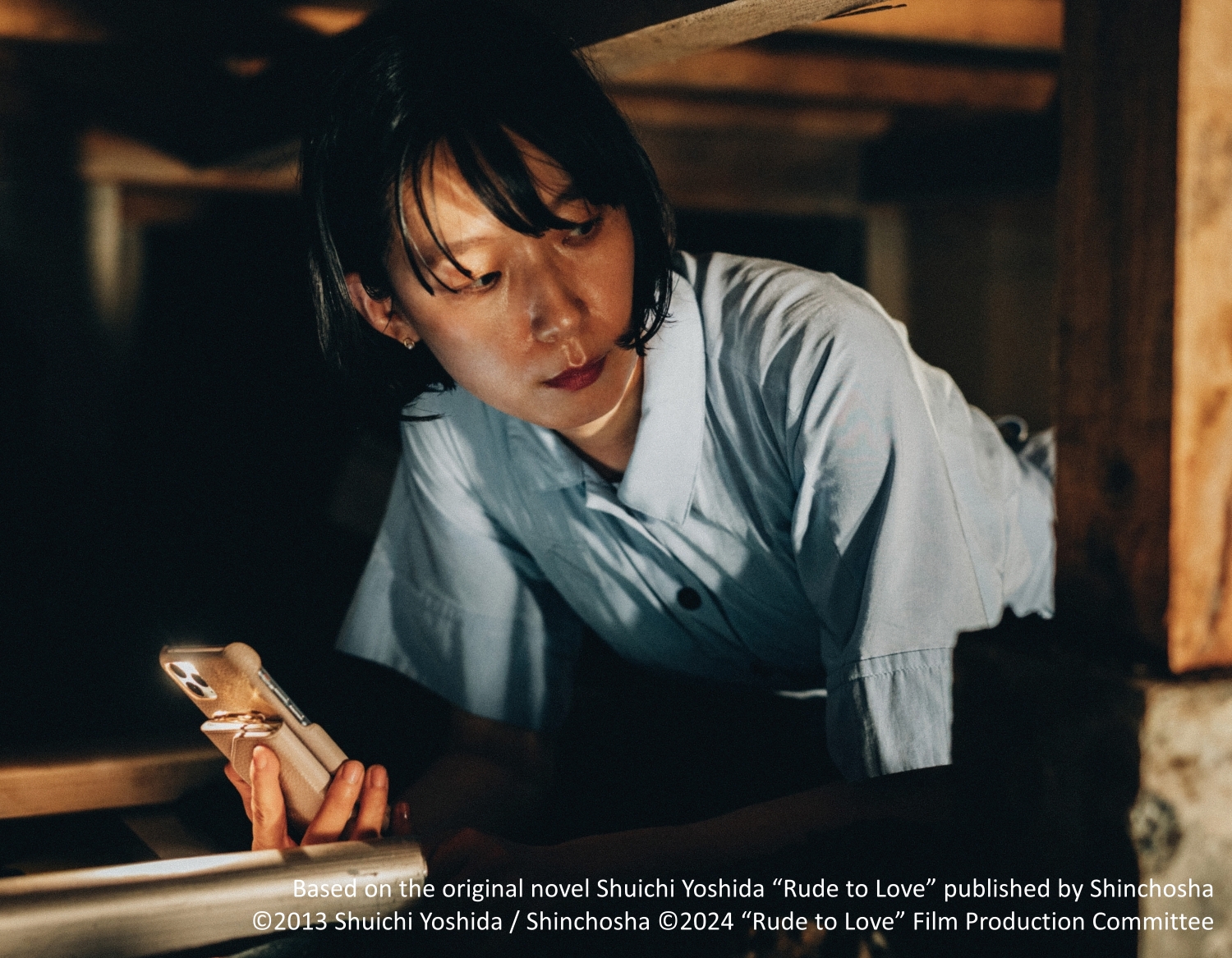

After the Snowmelt

Read more

Hayao Miyazaki and the Heron

Read more

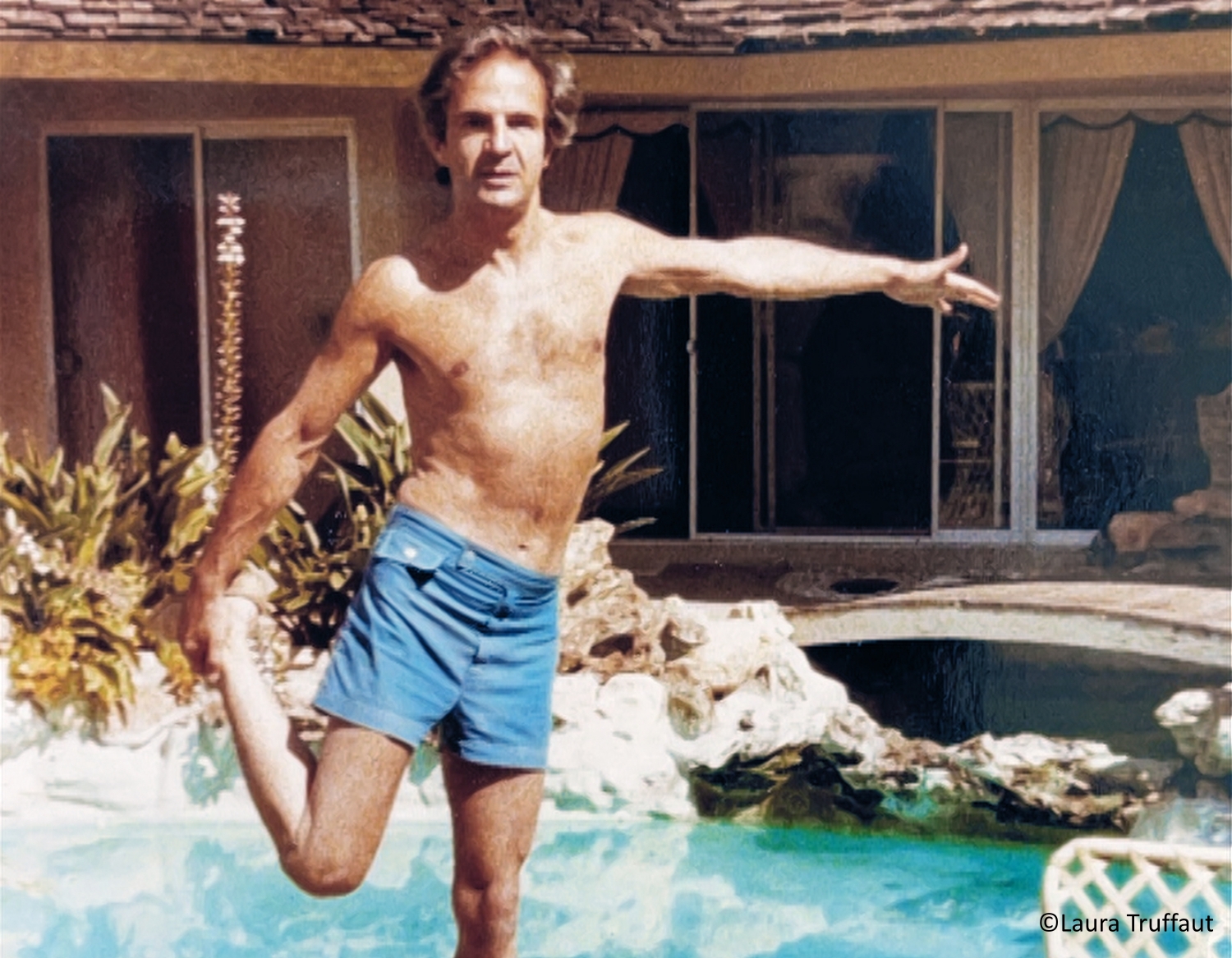

François Truffaut: My Life, A Screenplay

Read more

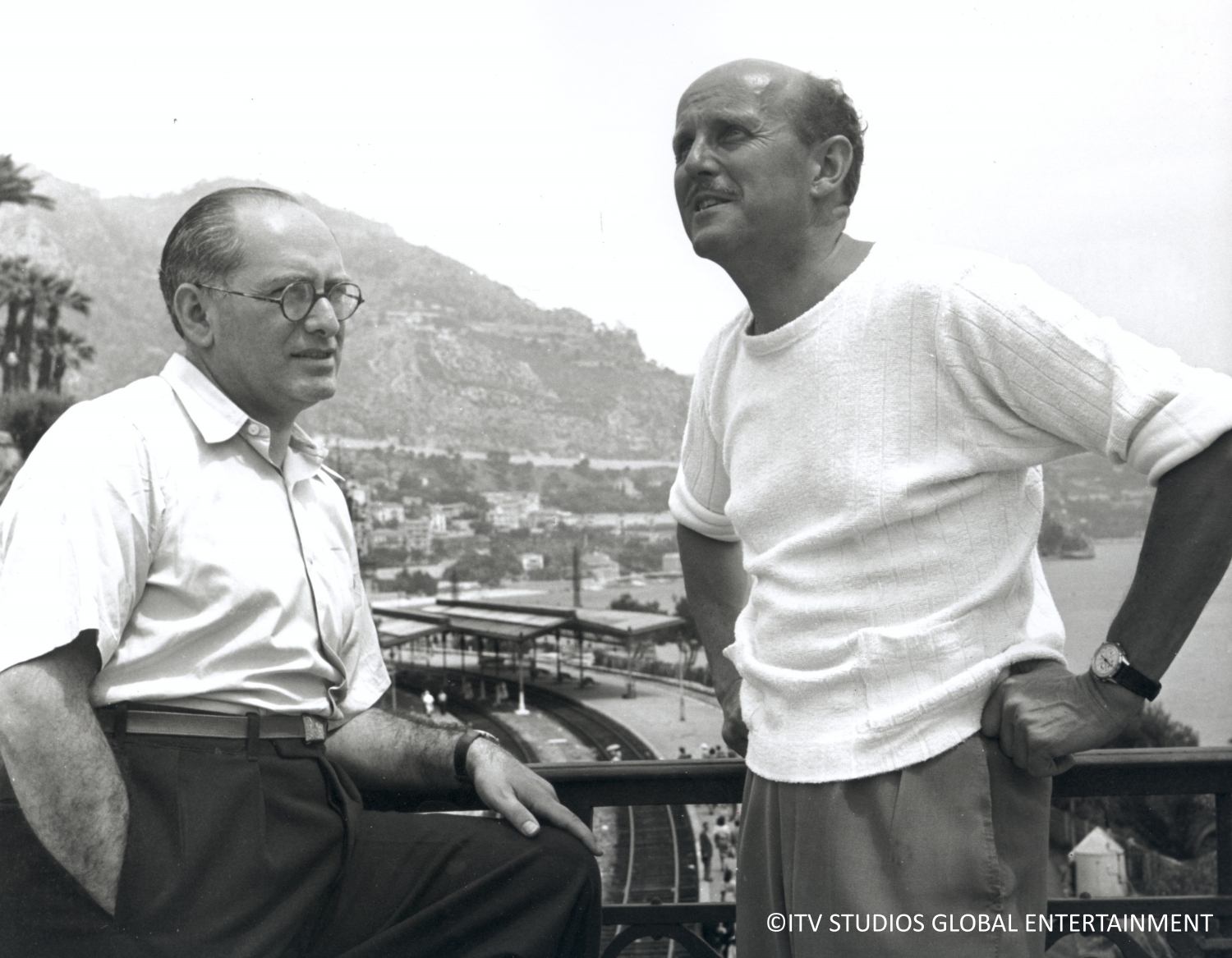

Made in England: The Films of Powell and Pressburger

Read more

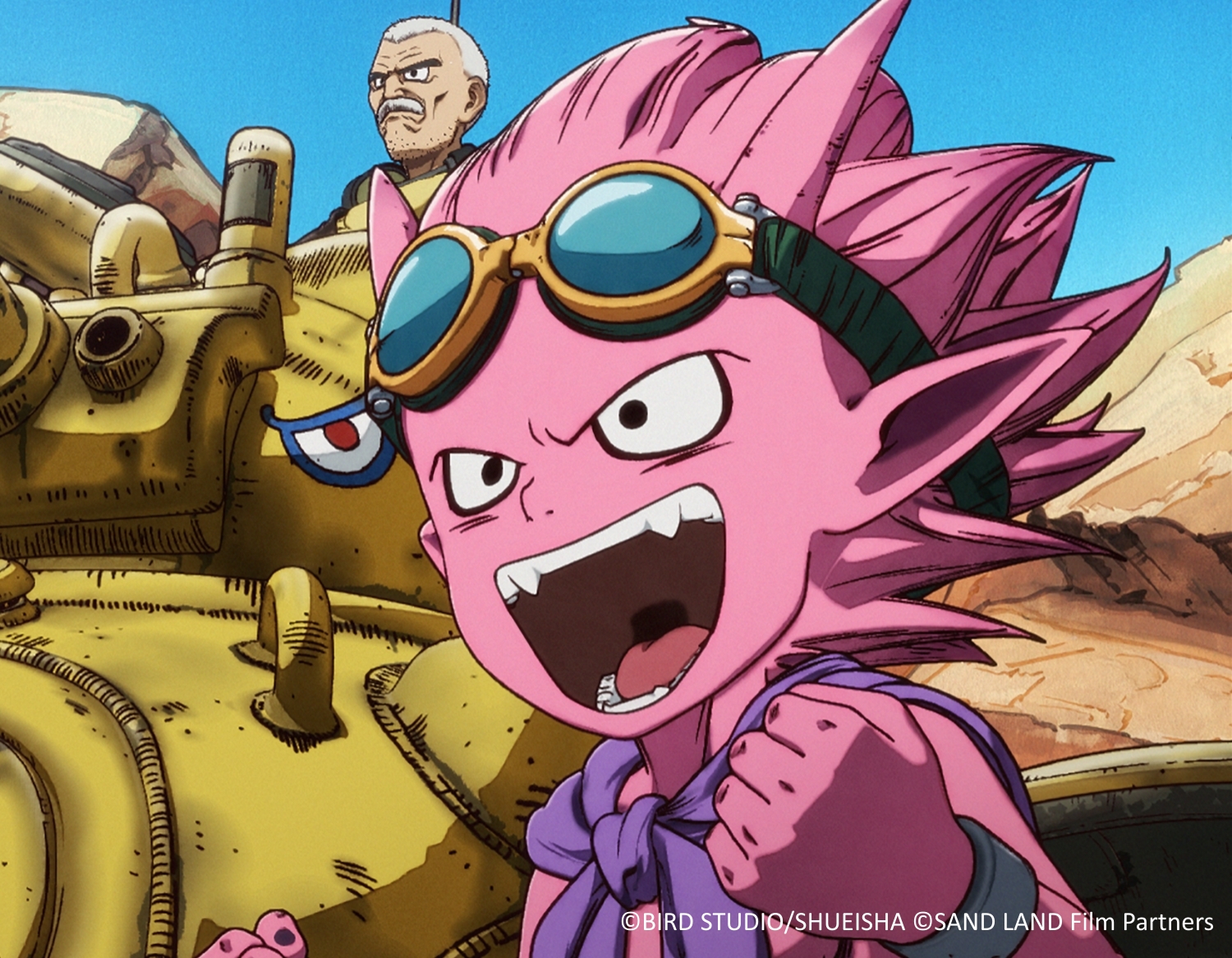

FANTASTIC BEATS

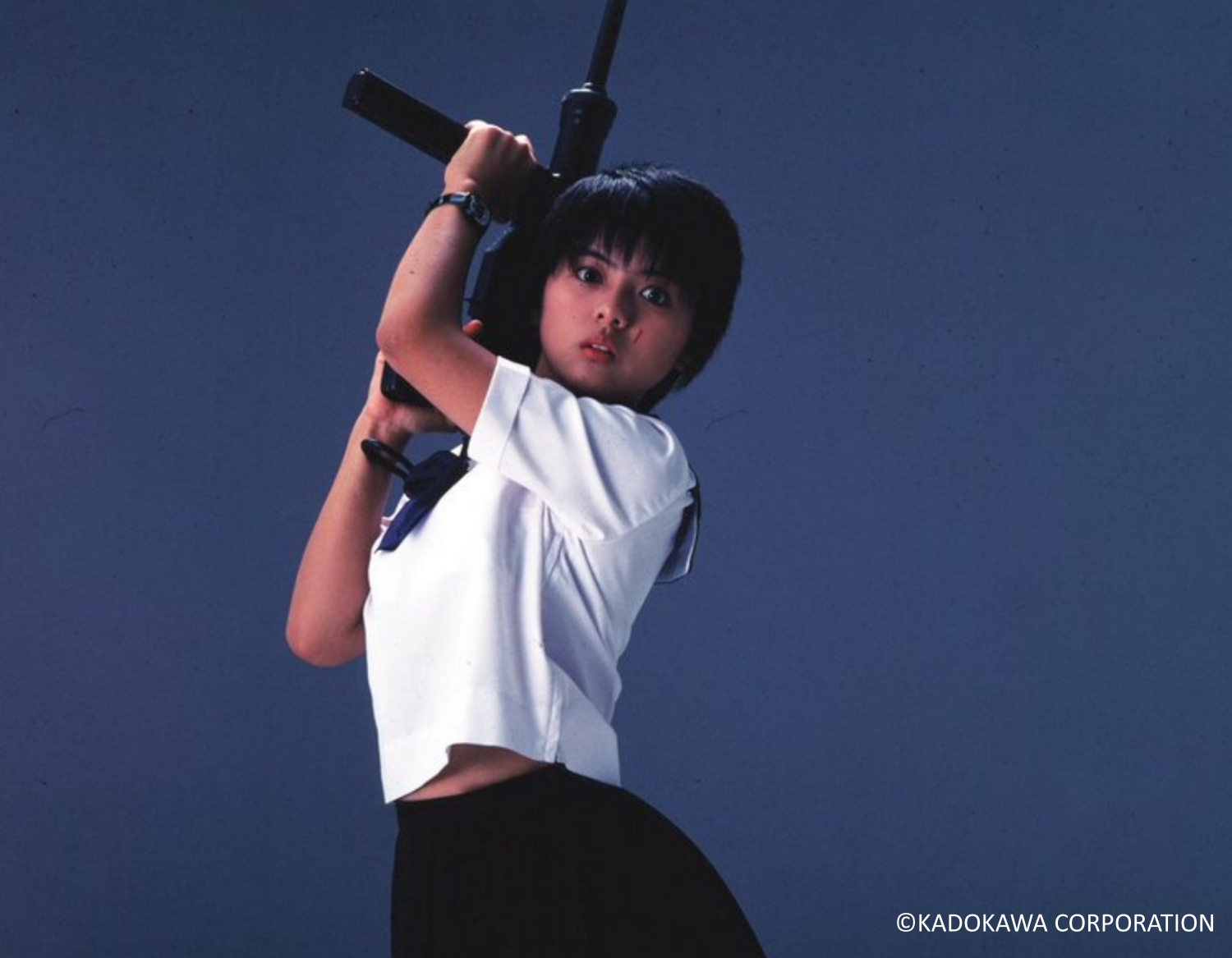

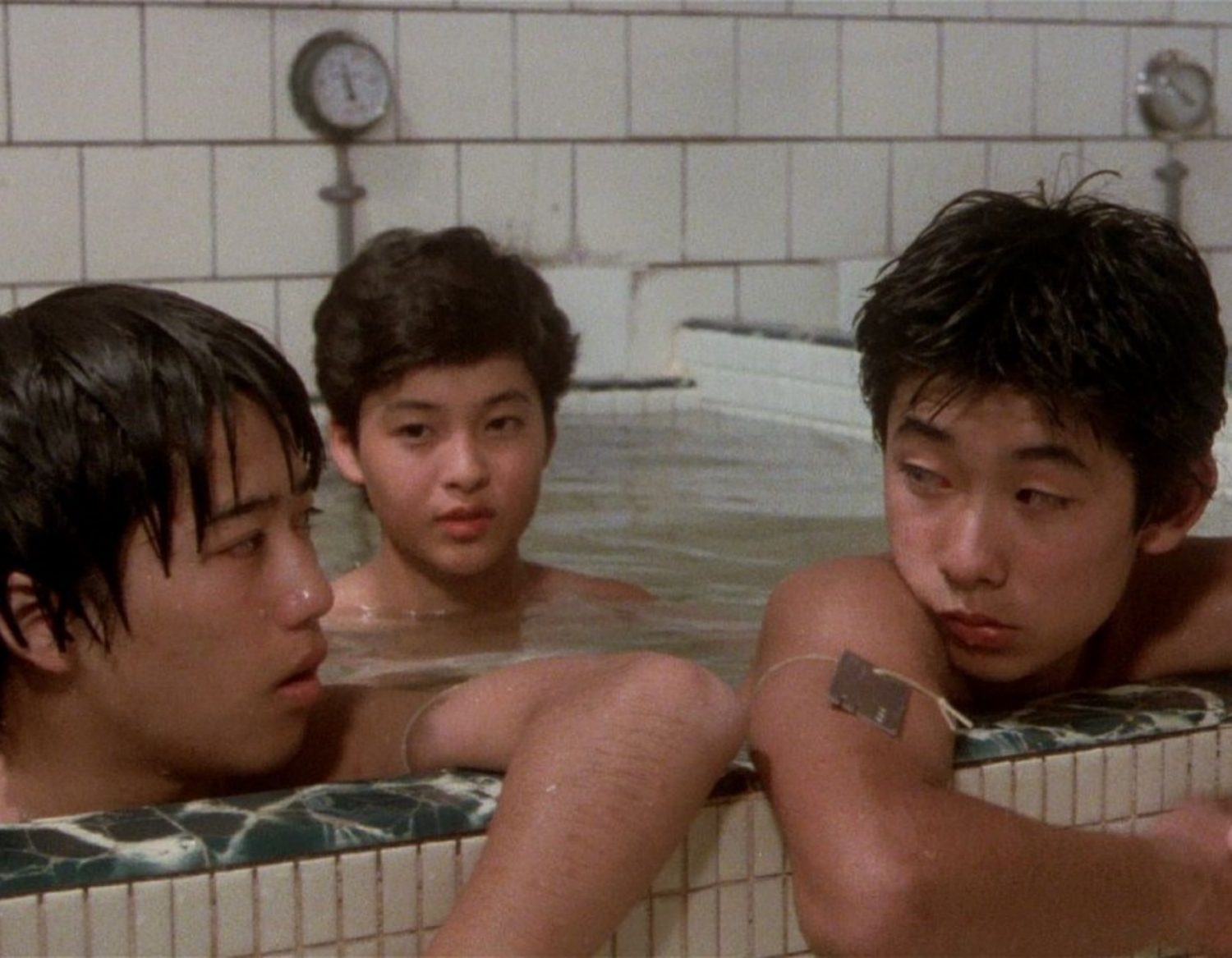

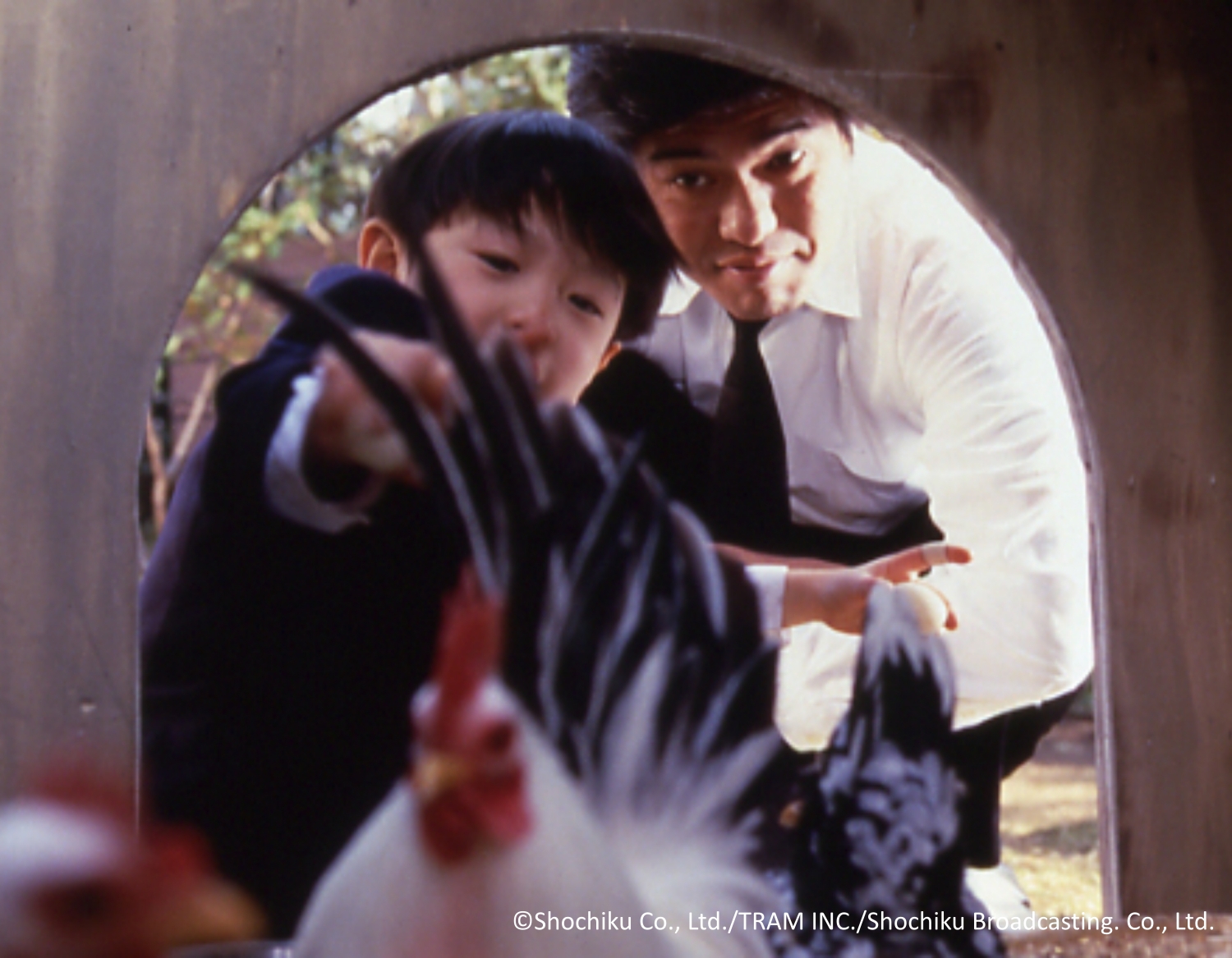

THE BEAUTY AND BRUTALITY OF YOUTH - THE FILMS OF SOMAI SHINJI

‘I can say with absolute conviction that no Japanese filmmaker makes a film without being conscious of [...]

‘I can say with absolute conviction that no Japanese filmmaker makes a film without being conscious of Somai Shinji’s existence.’ Coming from director Hamaguchi Ryusuke, this compliment is all the more powerful – the credentials of Somai’s influence can easily be found in the works of Kurosawa Kiyoshi, Aoyama Shinji, Iwai Shunji and Kore-eda Hirokazu.

Emerging in the early 1980s when Japan’s film industry was waning as the studio system fell apart, Somai broke the void of the ‘lost decade’ with his independent films of unbridled style and eclectic novelty – five of his pioneering works are listed on Kinema Junpo’s best Japanese films of all time. Most notable as an auteur specialised in seishun iga (youth film), Somai’s distinctive blend of wishful fantasy and daredevil inclination in his characters ignited an enduring pop culture phenomenon, and created a star vehicle for multiple teen idols – the most iconic being Yakushimaru Hiroko, whose image of holding a machine gun in sailor suit became a defining emblem of the young generation.

Rashness and disillusionment on the cusp of adulthood are recurring themes in Somai’s oeuvre. Structuring and shooting the film almost completely by Mizoguchi rules – one scene, one take, his fluid yet precise takes and unorthodox camera angles capture the different physical and emotional realities of adolescence and coming-of-age, and their manifold intersubjectivity. Astonishingly acrobatic and effervescent, his lens forces its way to match the spontaneity and volatility of his actors – running, jumping and tumbling to free themselves from the oppressive world of adults, while creating space for their outbursts of raw passion, explosive desire and anxiety. In his brilliant evocation of a youthful quest for freedom and change against the turbulence in life and death, Somai crystallised a profound portrait of the rites of passage, beautiful yet savage.

The age of Somai’s characters is irrelevant. Just as a youngster, a burly wrestler, a flabbergasted old man and a heartbroken hooker are all entrapped in loneliness and alienation, adrift in chaotic Japan under his visceral camera. The apotheosis of his long take that has the power to transcend space and time is found in the magic hour when the teenage girl experiences a dream-like revelation in a fire-illuminated lake, and equally in the delicate moment when the desperate mother dances in the dark snowy forest before attempting to end her own life. It’s magical realism in its purest form, evoking obscure existential musings on the inevitability of loss and passing. Leaving behind thirteen works before his untimely death at the age of 53, Somai’s spirit is still very much alive – in the timelessness of youth and cinema.