2025

Sweet Lie, Bitter Truth – The Cinema of Mike Leigh

Compassionate, incisive and strikingly true to life, the cinema of Mike Leigh follows a singular path from [...]

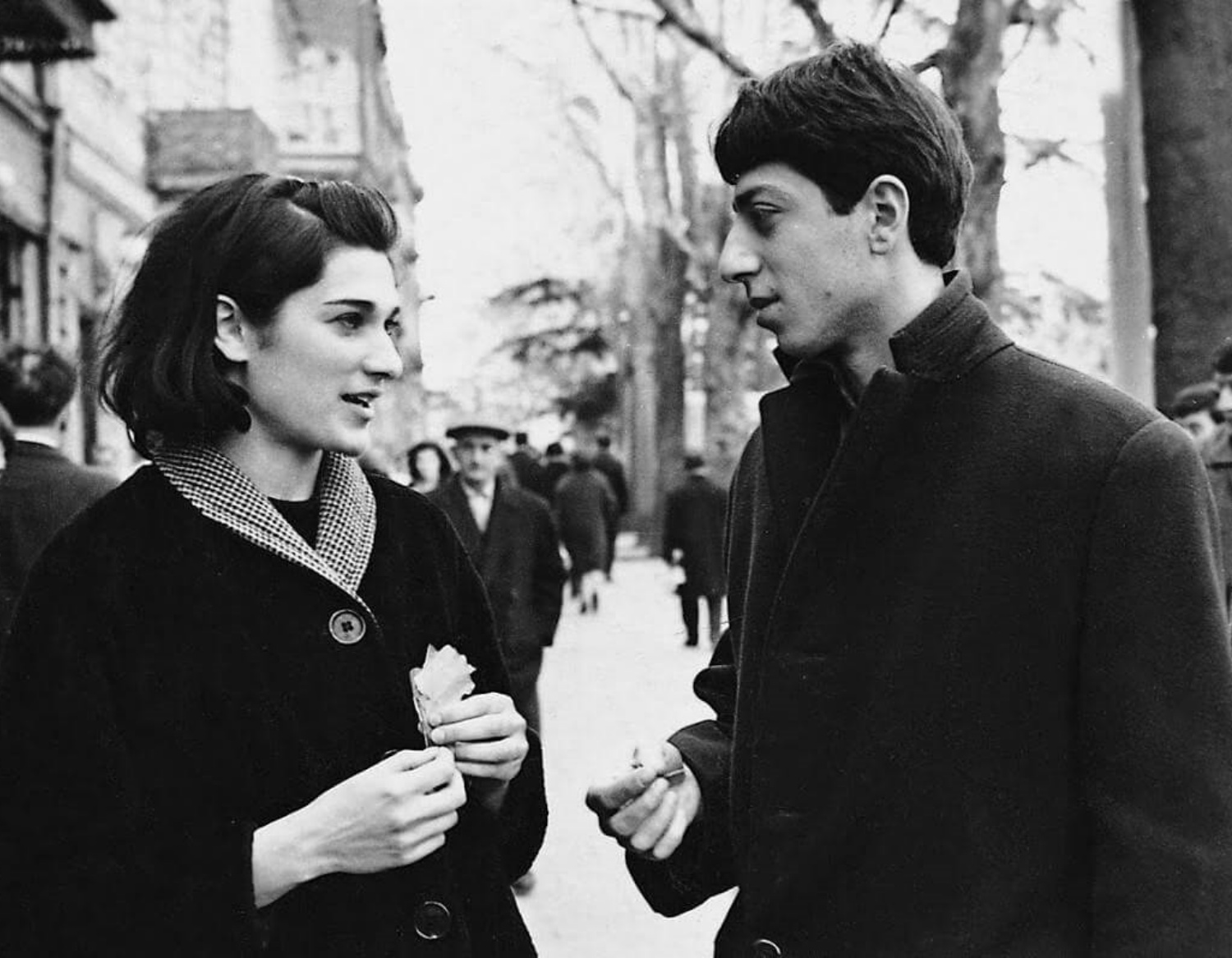

Compassionate, incisive and strikingly true to life, the cinema of Mike Leigh follows a singular path from conception to screening. His is an immensely watchable filmography showered with acclaim, yet founded on a collective approach that has given riskaverse producers the willies.

Leigh’s projects famously begin without a script. Instead, the director guides actors to work up plotlines and characters through months of improvisation, research and rehearsals. Performers draw on people they’ve known, and even learn the trades their characters live off. The organic process extends to side parts, and by the time cameras run Leigh’s cast members are steeped in their roles and the story falls into shape. The meticulous approach also encompasses great detail in cinematography, art direction and more, often from longtime collaborators.

Leigh first studied acting, before turning to filmmaking classes under the influence of world cinema. He directed theatre works for several years, then made his debut feature film Bleak Moments (1971), based on his own play and transferring his work process from the stage.

Leigh’s approach was already scaring off investors, however, and he spent more than a decade directing plays and movies for TV. His return to cinema was the contemporary social comedy-drama High Hopes, and more of the type would follow – not least the beloved Cannes Palme d’Or winner Secrets & Lies. But Leigh’s cinema isn’t easily pinned down. Warmth and humour can spring from even the most crushing situations. Naked operates on a far darker level than earlier works, while the heartbreaking Vera Drake deals with the controversial topic of abortion. And period films Topsy-Turvy and Mr. Turner hold fascinating examinations of creative forces in theatre and visual arts.

Yet no matter the genre or period setting, Leigh’s cinema is marked by an abiding interest in and empathy for those he portrays. Whether opening the door to understanding struggling parents, capturing working-class worries or zeroing in on a famed painter’s troubled soul, Leigh strives for a bracing realism and, with it, our immersion in the lives exposed onscreen.

Back to the Screen

Restored Classics

Of Levity and Humanity: The Otar Iosseliani Retrospective

Like a secluded poet, Otar Iosseliani (1934-2023) is probably the most mysterious filmmaker of the 20th century. [...]

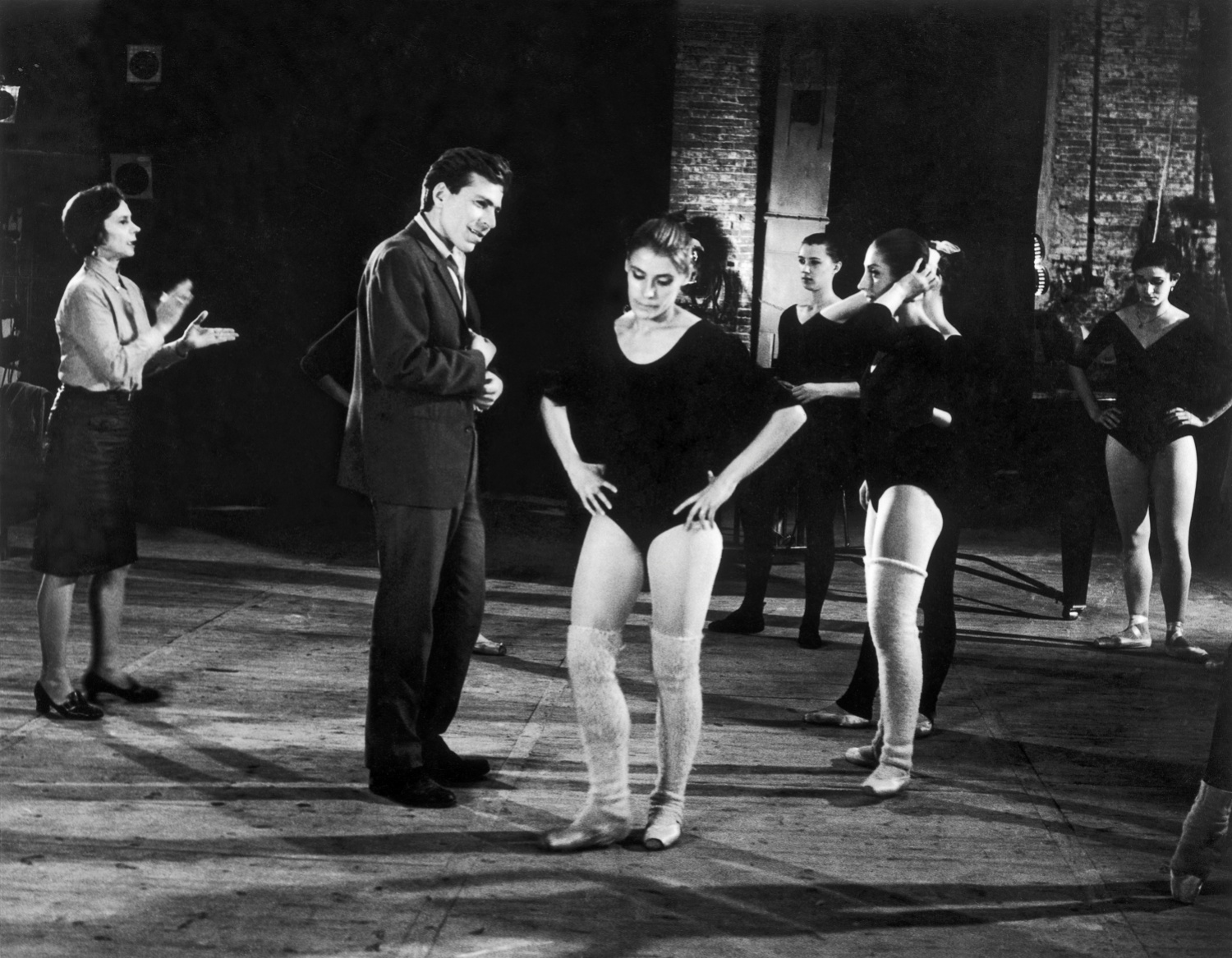

Like a secluded poet, Otar Iosseliani (1934-2023) is probably the most mysterious filmmaker of the 20th century. His unique way of looking at the world blossoms his cinematic visions, and a distinctive Iosselianian universe: convivial, sublime, with whimsical humanity.

1934 was the year L’Atalante was released and Iosseliani was born. Fate has it that Jean Vigo’s anarchic cinema served as his inspiration. A graduate of VGIK, he never abided by the orthodoxies of socialist realism, and expressed disdain for ‘monumental figures’ like Eisenstein for surrendering to party ideology. It’s no surprise that all his films fell foul of the Soviet censors.In 1982, he decided enough was enough and left to live in Paris.

Iosseliani’s cinema stands apart from the rest. Like a therapeutic antidote to the tyrannical bitterness of pedantry, the profound levity of his cinema serves as an ode to life freed from dogma. Discarding any kind of cohesive narrative, his films are loosely episodic and hardly plot-driven. His kaleidoscopic characters weave the narrative through their movements, dispersing in random directions yet interconnected with creative use of sound, skilful editing, and meticulous mise-en-scene. It’s a unique rhythm of its own, evoking musicality that blends the gentle absurdist humour with the leisurely pace to form his inimitable, idiosyncratic fables.

Regarded as the true heir to Jean Renoir, Jacques Tati, and Luis Buñuel, Iosseliani’s cinema is infused with poetic realism, comic rhythm, and subversive vision, yet he made it clear that he only ‘stole’ from paintings, music and literature. It is no coincidence that thieves always appear in his films, stealing almost everything – from paintings to money, silver spoons, wine, and even personal freedom. ‘Everything that happens in my films has to be with people’s weakness for possession,’ says Iosseliani. ‘And this leads to real values such as feelings disappearing.’ By stealing away all the unnecessary from life and frame, what remains is the essence – true moments of passing life.

Like stealing, drinking wine is indispensable in his films. His passion for vodka became a way of interpreting the world. Quietly flourished in the poetic distance between his lens, the characters and reality, his self-described ‘abstract comedies’ find pleasure in the minutiae of quotidian existence amid his incisive explorations of human absurdity, while yielding a sharp satire on the greed and emptiness of bourgeois society. And it is the delicate balance that puts the world in the right order.

Otar Iosseliani Short Film Collection

Read more

Falling Leaves

Read more

Once Upon a Time There Was a Singing Blackbird

Read more

Pastorale

Read more

Favourites of the Moon

Read more

And Then There Was Light

Read more

Chasing Butterflies

Read more

Brigands, Chapter VII

Read more

Farewell, Home Sweet Home

Read more

Monday Morning

Read more