2016

Paul Verhoeven, The Gutsy Provocateur

At age 78, Paul Verhoeven managed to anger, divide and delight audiences at Cannes this year with his latest feature, Elle, an unusual story of rape and revenge which many American actresses had rejected. Sensuality, violence, complex (and dangerous) women and strongly creative men have swirled through the director’s work for decades, in his native Netherlands and his adopted Hollywood home in a process of constant directorial reinvention. Championed as the best of Dutch filmmaking, scorned for his misogyny and misunderstood for his satire, Verhoeven leaves an impression – and arguments – with every film.

Born in Amsterdam in 1938, Verhoeven grew up in wartime Holland before pursuing advanced education in sciences. Yet his attraction to film proved overwhelming even in his military service, and his Dutch films offer thoughtful explorations of love, patriotism and injustice amid death and betrayal. After two decades, he moved to America, exchanging arthouse films for big-budget movies where his explorations of sex, violence and identity became bigger but not always successful. In a third stage, Verhoeven moved back to the fami liar territory of wartime relationships and betrayals to regain his position as a major Dutch filmmaker before challenging the world with his vision of women and power at Cannes.

How do we read this elusive director, who can evoke tender emotions in complex stories told through beautiful cinematography that demand the attention of a festival audience and then produce a box-office smash like RoboCop (1987) or an epic failure like Showgirls (1995)? What are the links between the used women of so many early films and the female routes to power that unnerve us in later films? The homosocial (and homosexual) relations of men and women that so easily become betrayals as well? The fascination with religion – Verhoeven wrote a book on Jesus of Nazareth and has talked about a film – that sometimes seem to shake the very foundations of morality? Verhoeven’s works remain powerful questions with few easy answers: a cinematic journey over five decades with no signs of slowing down.

Elio Petri, the Italian Satirist

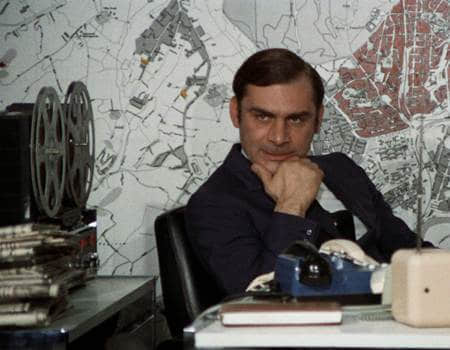

Italian director Elio Petri (1929-1982) embraced communist philosophy, and the political subtext of his films [...]

Italian director Elio Petri (1929-1982) embraced communist philosophy, and the political subtext of his films revealed both his disdain for right-wing corruption and devotion to the working class. Petri, who was born in Rome and once wrote for L’Unità , the newspaper of the Italian Communist Party, began working in cinema as a scriptwriter in the 1950s. He made his directorial debut in 1961 with The Assassin, a noir-ish tale about police investigating a murder suspect. The film, critic Pasquale Iannone wrote in Senses of Cinema, stands out “as one of the finest Italian debuts of the 1960s, setting out the themes and preoccupations that Petri would return to throughout his career.” Petri’s films – which routinely incorporated parody and black humor to chilling effect – are blistering attacks on unchecked political power, brutal law enforcement and crass consumerism. Italy’s long-ruling and scandal-ridden Christian Democracy party was often, even in oblique terms, the target of much of his scorn.

Petri became a leading figure in post-neorealism Italian cinema of the 1960s and 1970s. He collaborated frequently with Marcello Mastroianni and Gian Maria Volontè, two of the eras leading stars; critically acclaimed screenwriter Ugo Pirro; and Ennio Morricone, whose iconic film scores have made him one of the world’s most celebrated composers. He gained further attention with Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion (1970), a sadistic satire about police corruption, which won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. Still, Petri’s name is now rarely mentioned alongside the masters of Ital ian cinema: Fellini, Antonioni, De Sica, Pasolini, Bertolucci, Visconti.

But his films today resonate with stunning prescience of modern civilization’s bleakest elements. His most politically potent film, Todo Modo (1976), explored power among Italy’s political elite and dared to sabotage the notion that one man alone could rescue a nation from its problems. With The Tenth Victim (1965), he anticipated the perversity of reality television, widespread gun violence, and unbridled corporate greed. Petri, speaking with The New York Times, once said that he hoped audiences would see “what could happen if we continue our current trends in society. That violence may be the end of everything and if we don’t stop soon, there’s no guessing what will happen.”

Naruse Mikio: Women, Destiny, Independence

On the centenary of Naruse Mikio in 2005, we wanted to organize a large scale retrospective like that of Ozu Yasujiro. Due to limited resources, however, we could manage some small scale film classes only. Ten years later, we have finally presented 12 of Naruse’s masterpieces on his 110th, with enthusiastic response from the Cine Fans. At the beginning of this year, we added two more titles to our “Naruse Mikio Encore!” programme. Now, a film course in 6 classes is organized to further promote and arouse the interest in Naruse’s films. Grab this opportunity to watch his films on the big screen and enjoy the film course that follows.