2018

Beyond a Reasonable Doubt: In Search of the Truth

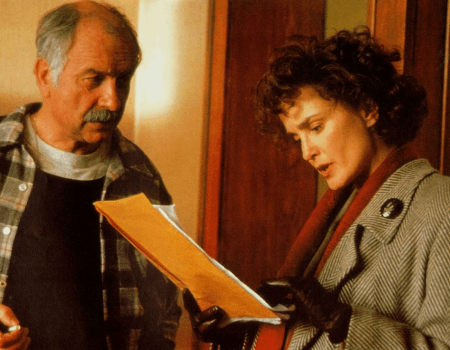

Police dramas lure us into the excitement and intelligence of the chase. Yet, once the suspect is caught, the cops’ task eventually gives way to the deliberative and thoughtful pace of the prosecution and defense, the rituals of the courtroom.

Major directors turn away from guns and cars to explore the many facets of proof as well as the ways in which personal conflicts intersect with deliberations about concrete crimes and more abstract concepts of truth, judgment and justice. It is no longer the cowboy cop or the masterful criminal who keeps us on the edge of our seats. Courtroom dramas include, instead, a wide host of potential players – the attorneys, the judge, the juries, the witnesses, the defendants and even family plaintiffs, whose roles are refracted across systems and cultures in this compelling docket. Issues as pressing as generational anger, racism, sexism, violence, family and political torture. And one long take on a conflictive jury fighting its way to the truth.

There are rituals to every trial which guide us but the characters also take their work home – whether haunted by questions raised and unanswered or stymied by the logistics of the trial. Most of all, courtroom dramas create a serious cinema of multiple layers of meaning, where the compelling narrative arc of a central story always proves less than the lesson – indeed, the moral – of the story as a whole. Movies honed by words of deliberation, the character of the players and the inevitability of judgment, that will challenge us as well before we put the trial behind us. Time to get off the mean streets and into the courtroom as a summer of crime and punishment continues. See you in court!

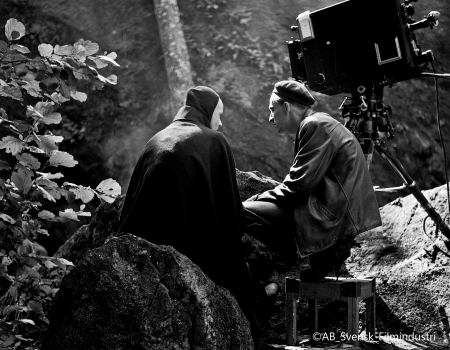

Ingmar Bergman, Faith and Faithfulness II

The end is just the beginning. Ingmar Bergman (1918 – 2007) has left, but never vanished. Like [...]

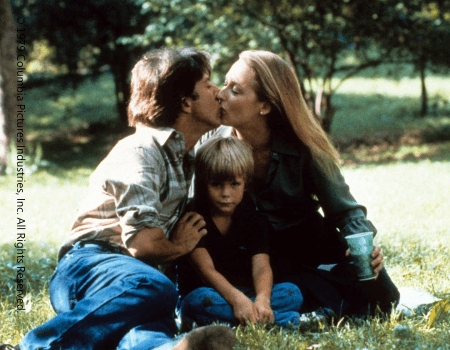

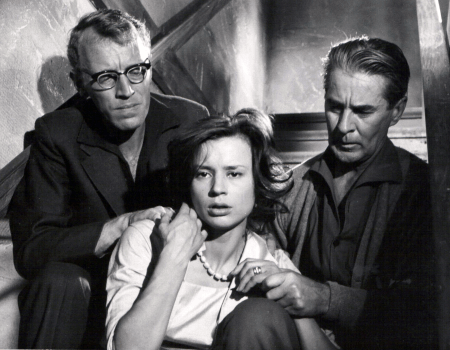

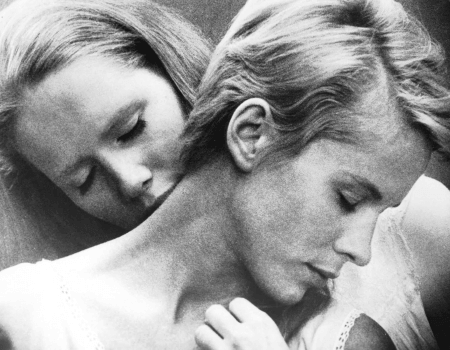

The end is just the beginning. Ingmar Bergman (1918 – 2007) has left, but never vanished. Like the ghosts drifting through his hypnotic, haunting masterpieces, his plague of the modern soul and visions of spiritual longing linger in the world of cinema and continue to inspire generations of filmmakers – an encounter with death in The Seventh Seal (1957) has been referred to by Woody Allen and David Lynch; and juxtaposed faces in The Silence (1963) are omnipresent in Alain Resnais and Andrei Tarkovsky’s films.

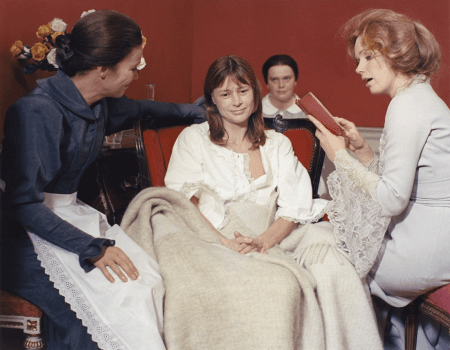

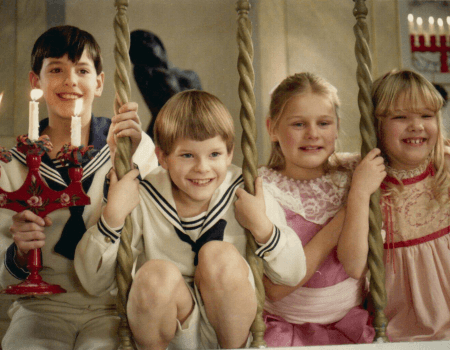

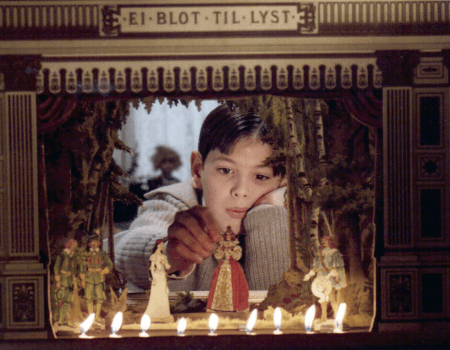

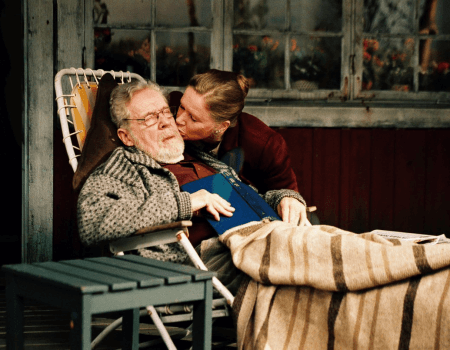

In over 60 films in his life, Bergman’s spiritual quest was underscored by his growing up in “emotional poverty”. Cutting into his own fears and analyzing his failings, he portrayed devastated men and women in tortured confrontations with an absent God, and futile attempts at romantic involvement or reconciliation. His bleakest vision of isolation and rejection, and of unrequited love, found its “real home” in the barren island of Fårö. The desolate, stony landscape became the backdrop of his six films, and the distinctive metaphor for his characters’ inner emotional states – descending into madness (Through a Glass Darkly, 1960), and experiencing mysterious spiritual transference (Persona , 1966). Finding security inside the stone walls, he released his doubt, hate and repentance in the most vibrant of colors – red, as the interior of the soul, painting the passion and emotional intensity in Cries and Whispers (1973) and Fanny and Alexander (1982), two of his most acclaimed masterpieces. After orchestrating his aching swan song Saraband (2003), he directed his own danse macabre in peace.

A life knowing too well what Death looks like, Bergman could finally get it out of his thought. Now living permanently in his heavenly dreams, his legacy, like his dreams, will live for eternity.