2018

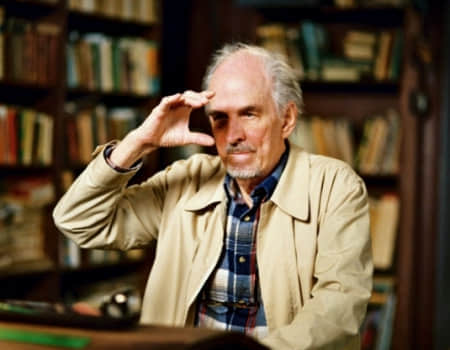

Ingmar Bergman, Faith and Faithfulness

In the beginning there was darkness. Beyond consciousness, straight to the emotions, and deep into [...]

In the beginning there was darkness. Beyond consciousness, straight to the emotions, and deep into the psyche, Ingmar Bergman (1918-2007) led us into our heart of darkness, face to face with solitary, vulnerability and torment. A rare filmmaker who epitomized the concept of existential and philosophical relationship drama, the legendary Swedish master has developed an unfathomable film language that is spoken from soul to soul.

A magic lantern lit up the way to his dreams, where he used cinema as an exploration, or exorcism, of personal demons. Monolithic shadow of his father, and the little devil that would eat his toes off in his childhood nightmare, penetrated his characters’ subconscious, revealing themselves in very stark and almost horrific scenes (Hour of the Wolf). In striking visual poetry, he forced us to confront our deepest fear and anxiety that we would rather shy away from.

Bergman’s films are solemn meditation on God’s enduring silence and on the specter of devil. Died at 89, death is an event on which he long contemplated and provided his most famous images – an old professor discovering a coffin containing his own still-living corpse (Wild Strawberries); and a dance of mortality led by the hooded, black-clad figure of Death (The Seventh Seal). He chose to shoulder the austere burdens of questing for the harsh truths about God’s existence and human nature, through the merciless rape and murder of an innocent maiden (The Virgin Spring), and the struggle of a couple to survive a savage war (Shame).

Yet in a tableau of lamentation and emotional violence, he faced life with a ruthless frankness, and didn’t forsake light and hope – illuminated by the enchanting whims of The Magic Flute , and this time his magic lantern reveals his passion for and accomplishments in the theatre.

On Bergman’s centenary, Cine Fan launches a retrospective in honor of the cinematic genius, revisiting his body of work that brought a new level of psychological depth to cinematic arts. More iconic works to come in our Sep/Oct edition.

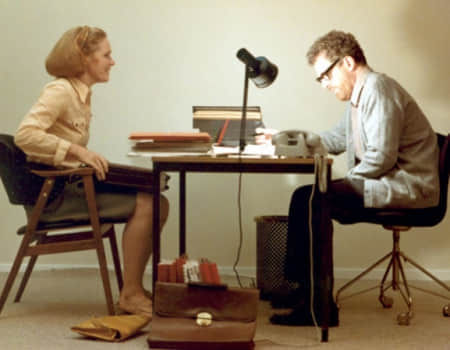

Beyond the Long Arm of the Law

What is it about cops in action on screen that draws us into their pursuit of justice? Not the cool analysis of a detective mystery with the brain cells of Hercule Poirot or Sherlock Holmes. Nor the suave elegance of James Bond in an exotic locale with a vodka martini, shaken, not stirred. Neither superheroes nor wolf warriors fighting monstrous supervillains, human or otherwise. Instead, these are movies about basic policemen and the law in its everyday incarnations. Trying to resolve crimes, protect the innocent and mete out punishment. City cops in tough towns. Guys – and one tough woman – with badges and an alltoo- expendable partner. And the violence that haunts them.

Generally, these are movies about men with men – surrounded by colleagues, bureaucrats, politicians, gangsters, occasional bystanders. And Frances McDormand in the wry world of Fargo. Some of the men are the bad guys (even when there are women there are always bad guys) who engage cops in tortuous pursuits across – and even under – urban landscapes (and occasional towns in the American South and Midwest). Not supervillians. Just guys. Kinda like the cops. Only bad. Which the cops are not, mostly.

Yes, there are women. Even Fargo reminds us that most often the women turn into victims of either the murderer or the cop himself. Kidnapped. Murdered. Or girlfriends and wives, neglected and damaged by men whose way of life threatens any relationship.

Besides, there is always another guy on the horizon. Partner. Chief. Killer.

Above all, these films are vehicles for iconic stars and chiseled dialogue, exciting scenography and great music. Cool jazz. Exciting chases. Acrobatic gunfire in a church. Revelations. And Sidney Poitier. Steve McQueen. Clint Eastwood. Chow Yun-fat. Alain Delon. Kitano Takeshi. Frances McDormand. And even Catherine Deneuve.

Remembering Isao Takahata

The passing of Isao Takahata (1935-2018) is more than a loss to Japanese and global animation. To many who have grown up with his Lupin the Third (1971) or Heidi, Girl of the Alps (1974), it’s the loss of a dear friend who has brought laughter and tears for half a century.

Setting his sights beyond traditional children’s fare, Takahata joined Toei Animation and spent three years on his feature directorial debut Little Norse Prince Valiant (1968), which was a groundbreaking entry in Japanese animation. The innovator has never ceased exploring a diverse range of themes and aesthetic styles – through a world of realism infused with fantastical imagery, he brought before our eyes war atrocities in Grave of the Fireflies (1988), regarded as one of the best anti-war films of all time, and critical environmental issues in Pom Poko (1994).

One of the co-founders of the renowned Studio Ghibli, Takahata has produced some of the most celebrated works of Hayao Miyazaki, including Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984) and Castle in the Sky (1986), the success of which earned Ghibli global recognition. His final masterpiece, The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2013), and his final artistic involvement in Ghibli’s first international co-production, The Red Turtle (2016), both received Academy Award nominations for Best Animated Feature Film. The Leopard of Honor award at the Locarno International Film Festival in 2009 was a celebration of his lifetime achievement.

His sophisticated, character-driven animations always find their mystical way into our hearts. From a girl’s nostalgic recollections of her childhood in Only Yesterday (1991); an ordinary family’s whimsical vignettes of mundane life in My Neighbors the Yamadas (1999); to the delicate moon princess confronting her fate in The Tale of the Princess Kaguya, Takahata seemed effortless in inspiring our empathy for his characters. Drawn in minimalist, fluid strokes and evocative watercolors, his films are stunning and whimsical, speaking to the deepest parts of our imagination and our soul.

Leaving behind a legacy of amazing works, Takahata will forever stay with us.