2018

Beyond the Wall: The Phantom of Liberty

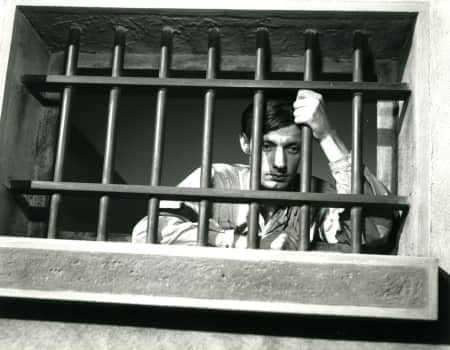

The crime films of the summer have taken us around the globe in thrilling chases and exploded in courtrooms with unexpected clues and connections. Yet these final, tightest of scenarios, confining their drama into the compressed walls of a prison, have fascinated directors, actors, cinematographers, set designers and audiences from the silent era to the present. Films where futures initially seem as closed as the barred doors locking the hero away from the world with its freedoms and pleasures. As we end up behind bars with them, we, too, look inward and outward for escape.

What else can our hero do when trapped by four walls, a tiny window, a nondescript uniform, occasional chains and the sheer monotony of food, exercise and loneliness? Meditate? Repent? Debate? Plan? In fact, these global films each take on the expectations of the prison cell to push the genre in directions that capture very different human spirits. Wrongly imprisoned in Maine or French Guiana? Time to Escape. Confined to a POW camp in World War I or II? Time to Escape. Trapped by brutality, torture, betrayal? Time to Escape. And in each plan, each vision, each attempt, we glimpse the liberty that may lie beyond, whether or not our hero ever reaches it.

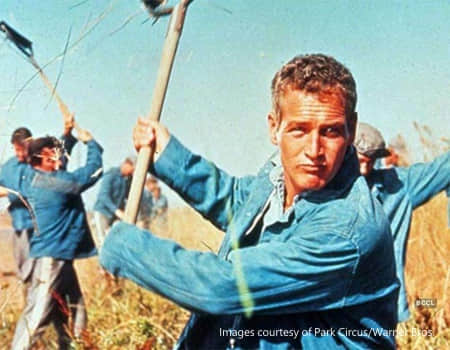

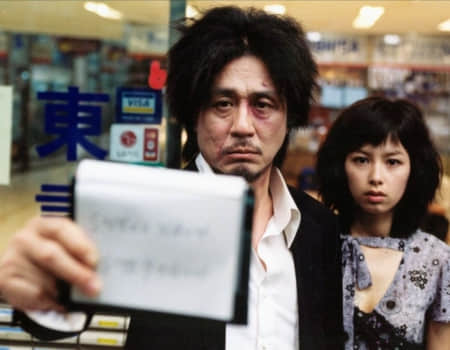

The challenge of prison and liberty demands powerful actors and directors who have taken on the challenge of confinement. Paul Newman. Steve McQueen. Dustin Hoffman. Jean Gabin. Erich von Stroheim. Choi Min-Sik. It is a male world where Gilda only appears as a screen poster idol and other women emerge only briefly to protect or betray. Yet, the writers and directors – Bresson, Renoir, Becker – have worked out the puzzle of how to keep our attention at fever pitch in a world defined by limits and repetition, with only the distant promise of an elusive glimmer of hope.

And so these films force us, too, to ask what freedom really means?

Marvelous Four: 100 Years of Polish Independence

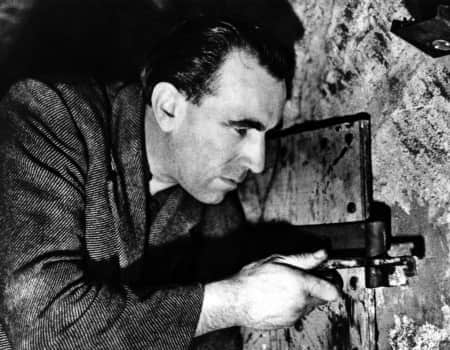

2018 marks the centenary of the state of Poland regaining its independence. After decades of partitions and serfdom, free Poland was reinstated on the map of the world. Emerging from the historical ordeal, filmmakers who remained unyielding inaugurated The Polish School. Starting with A Generation (1955), the pioneering work from Andrzej Wajda, Poland’s New Wave films stunned the international cinema not just for their historical and political significance, but for their free-spirited visual style and radicalization of the filmic language – strikingly thrived in the European land of liberty.

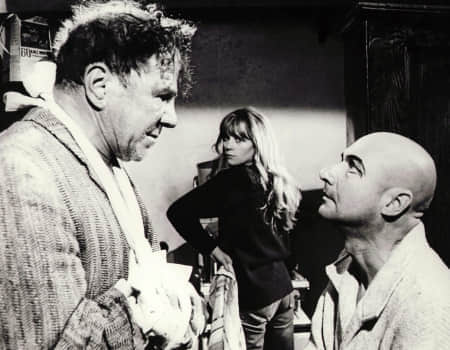

Roman Polanski (1933-) and the co-screenwriter of his debut feature Knife in the Water (1962), Jerzy Skolimowski (1938-), each in their own way transgressed the traditional methods of narrative building characteristics of their genres. Crafted with mind-blowing symbolism, Repulsion (1965) and Cul-de- sac (1966) break the threshold of psychological thriller and penetrate into the struggle of the human soul, asserting Polanski’s status as a master of world cinema. Whereas Deep End (1970) and The Shout (1978), two of Skolimowski’s finest films made during his exile in England, bespeak his prodigious talents and aesthetic conceptualization – unmatched anywhere else for his intuitive mastery of sound and imagery.

Beginning with experimental animation and transforming into fantasy and eroticism, Walerian Borowczyk’s (1923-2006) ingenuity and artistry is undeniable – comparable to that of Robert Bresson and Luis Buñuel. A surrealist and provocateur, he impressed the world with his cinematic poetry in multifaceted styles, from animated uncanniness in Theatre of Mr. and Mrs. Kabal (1967) to medieval romance in Blanche (1971). Another non-conformist visionary, Andrzej Zuławski’s (1940-2016) approach to storytelling is idiosyncratic and characterized by explosions of violence, sexuality, and despair. Portraying a tragic, shocking and hysterical vision of the world, Possession (1981) and On the Silver Globe (1988) evoke deep thoughts, nerves and senses in every respect that is unparalleled in any cinematic experience.

In an era of value crisis and fading hopes, it’s all the more important to hold on to the enduring creative spirit of these Polish mavericks.

Co-presenter of “Marvelous Four: 100 Years of Polish Independence”

Naruse Mikio: Floating, Drifting, Meandering

The winter may pass and the spring disappear, yet Naruse Mikio’s classics are coming back in the form of screening and lecture. Like “a deep river with a quiet surface disguising a fast-raging current underneath,” his timeless, elegant cinema deserves to be savored at the pace of life, and relished through the critical eyes of admirers.