2022

From Sexuality to Sanctity: Fiction Film Retrospective of Pier Paolo Pasolini

A Catholic, a Marxist and a homosexual in equal measure, the three identities of Pier Paolo Pasolini [...]

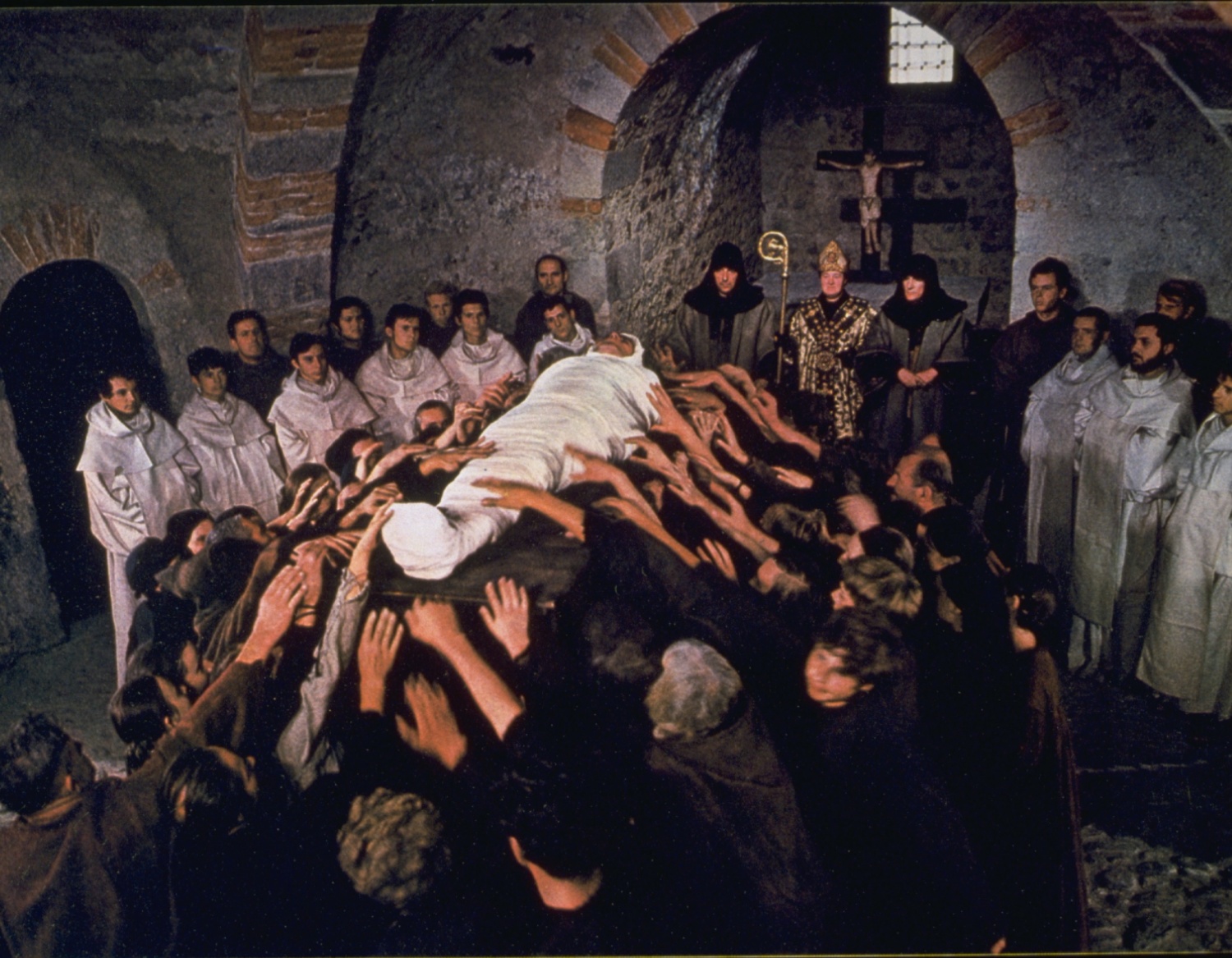

A Catholic, a Marxist and a homosexual in equal measure, the three identities of Pier Paolo Pasolini (1922-75), like the Holy Trinity, are interwoven in his works. From his directorial debut Accattone to his brutal murder at the age of 53, these identities, contradicting yet supplementing each other, combine to create a cinematic universe that constitutes a compelling, provocative, and transgressive vision of the contemporary world.

Facing a postwar Italy where the Fascist phantom re-emerged in neo-capitalist consumer culture, the poet expressed his intense loathing for bourgeois hedonism. In contrast, he caught a glimpse of sanctity in the underworld of the socially deprived. Through the shocking analogies of pimp as saint and whore as angel, he satirised the religious establishment by contaminating a sacred culture, while he discovered life's dignity in their desperate struggle for survival, and even saw the hope of salvation for the country. It is out of this socially marginalised reality that Pasolini created his cinema of poetry - existential, truthful and of stark visual beauty.

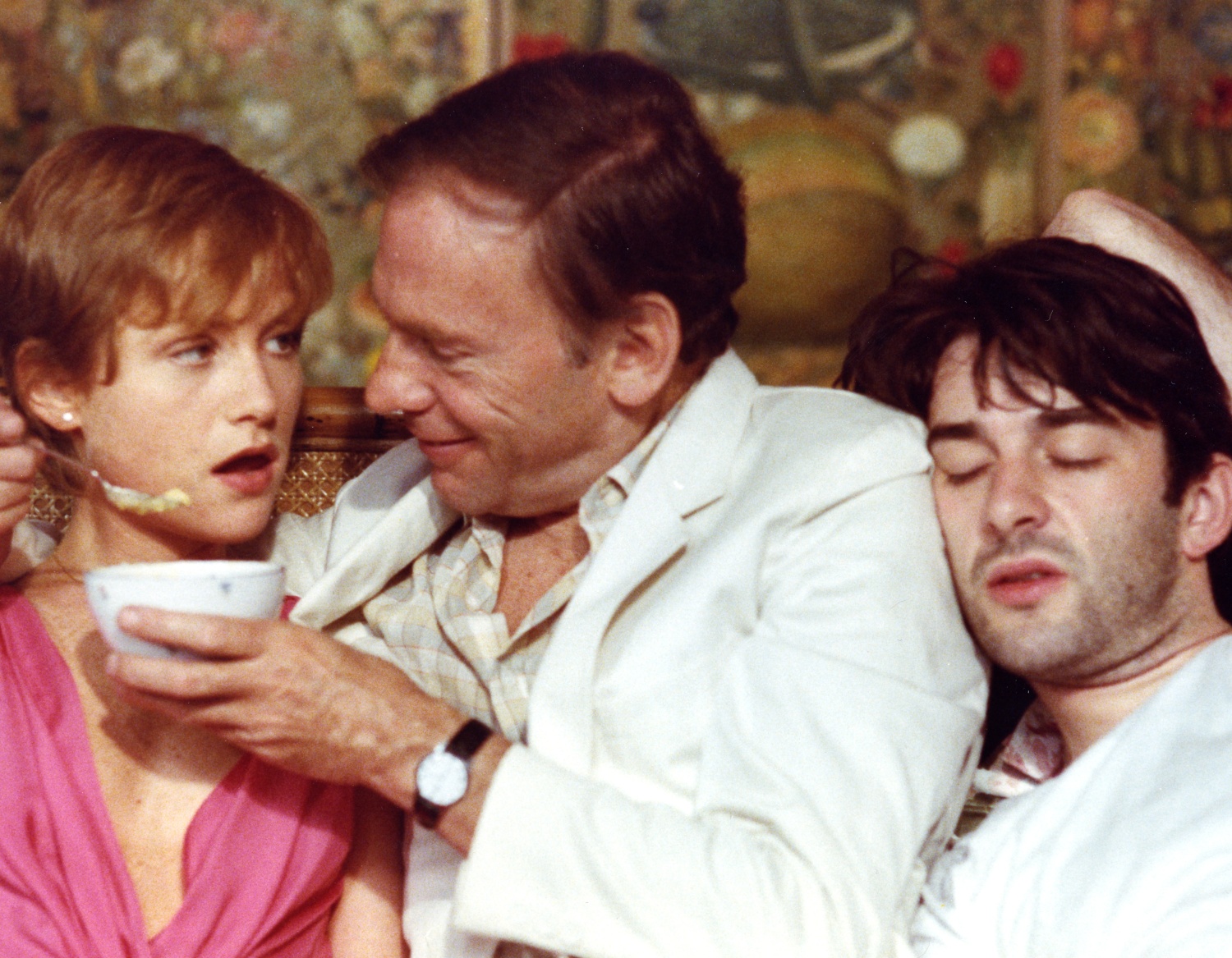

With a reactionary belief in the primitive body and instinctual desires as the touchstone of reality, Pasolini used explicit sex as a tool of ideological provocation, with the acid criticism on Catholicism, capitalism and the bourgeoisie in Ro.Go.Pa.G's Curd Cheese, and charging Theorem with sexuality as a sort of striking revelation and transcendence, at once scandalising morality, bourgeois hypocrisy and against nihilism.

Paradoxically, he realised that the sexual liberation serves to expand rather than subvert the culture of New Capitalism. Turning to medieval literature, he tried to historicise sexualities in order to create a virtual rupture in the lived experience of the contemporary world in his Trilogy of Life, a highly acclaimed work which he himself later repudiated. In a radical transformation he shifted to the exploration of the human capacity for cruelty, perversity and sexual sadism bordered on the unimaginable in his political allegory Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom, decrying his most violent and outrageous remarks on the decadent society.

On the 100th anniversary of Pasolini's birth, we pay homage to one of the world's leading left-wing intellectuals with a retrospective comprising all of his fiction feature and short films, seeing him anew as a poet, master filmmaker, and even a prophetic enlightener.

Co-Presented by

Supported By

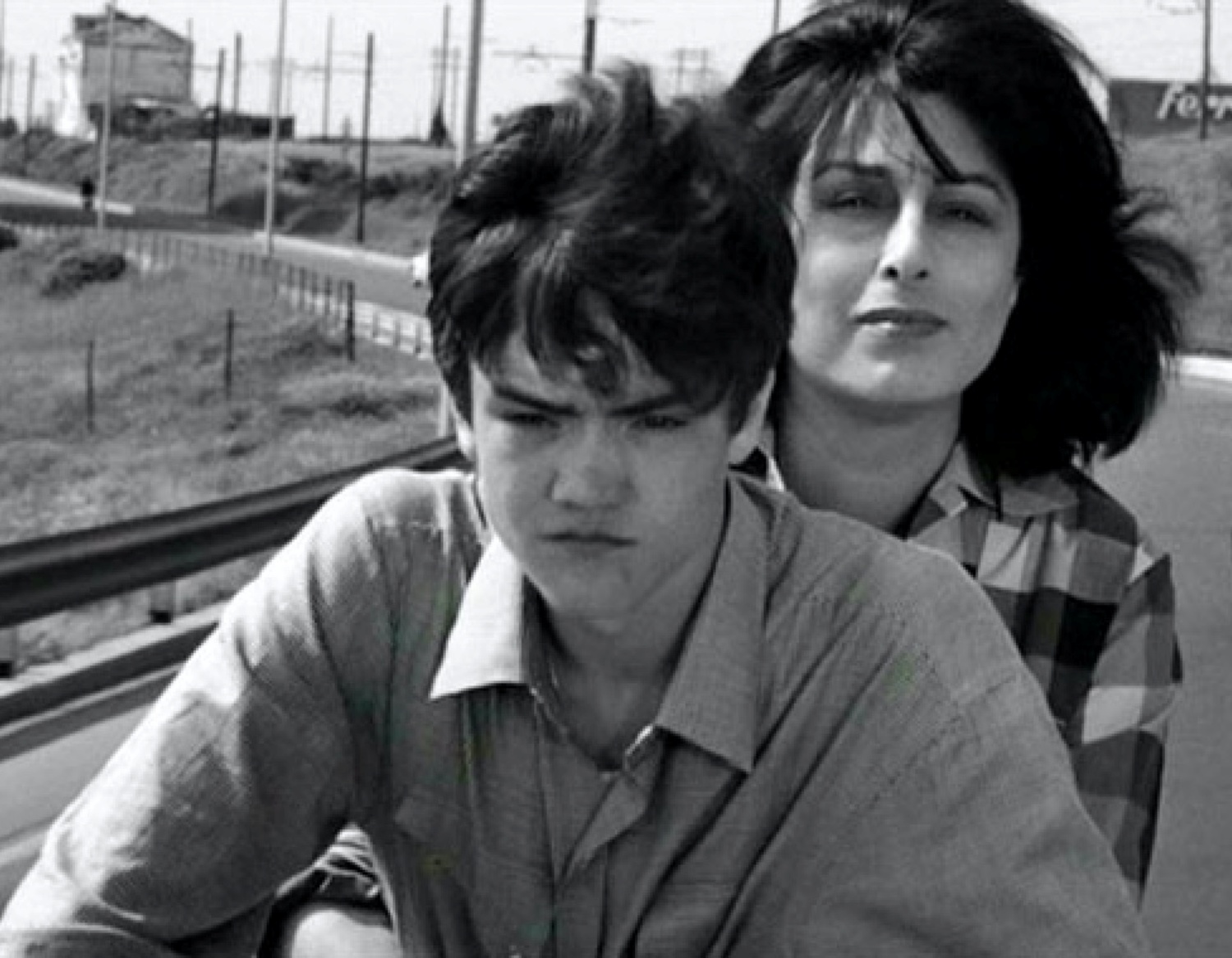

Accattone

Read more

Mamma Roma

Read more

Ro.Go.Pa.G

Read more

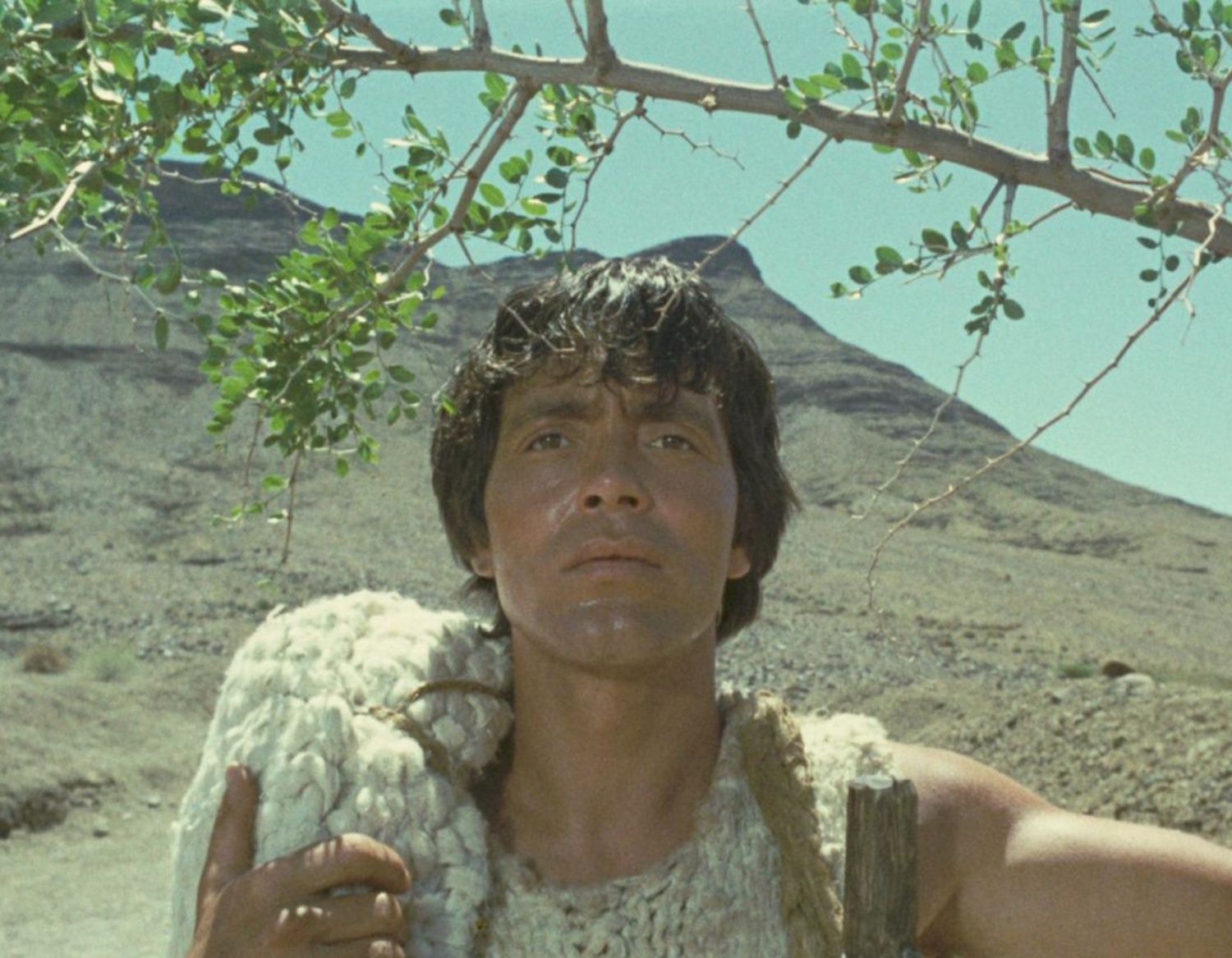

The Gospel According to St. Matthew

Read more

Hawks and Sparrows

Read more

Oedipus Rex

Read more

Theorem

Read more

Pigsty

Read more

Medea

Read more

The Decameron

Read more

The Canterbury Tales

Read more

Arabian Nights

Read more

Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom

Read more

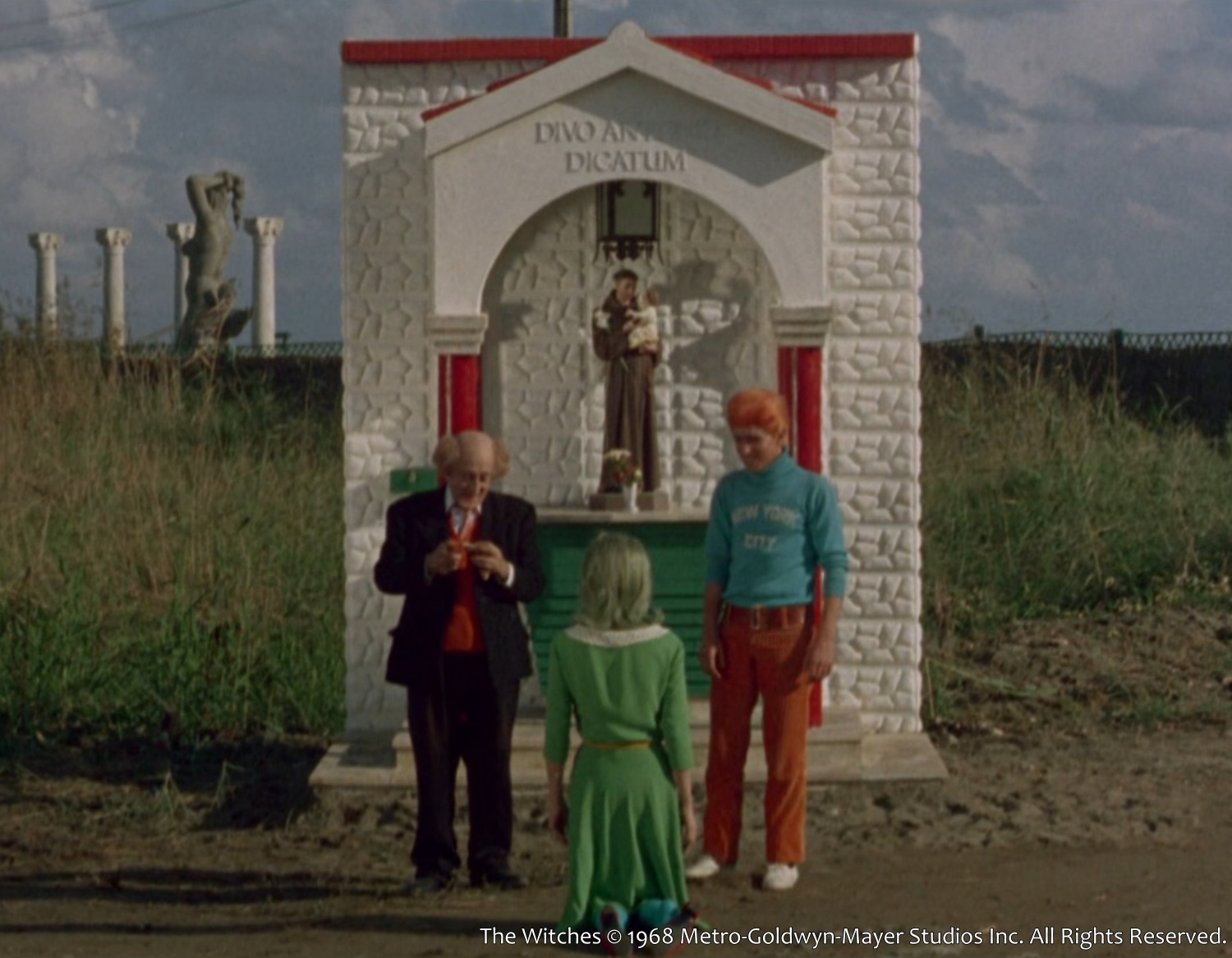

The Earth Seen from the Moon (From: The Witches)

Read more

What are the Clouds? (From: Caprice Italian Style)

Read more

The Paper Flower Sequence (From: Love and Anger)

Read more

The Wicked Charm of the Talented Ms Highsmith

We are often compelled and gripped by salacious tales of crime and punishment, and there are very [...]

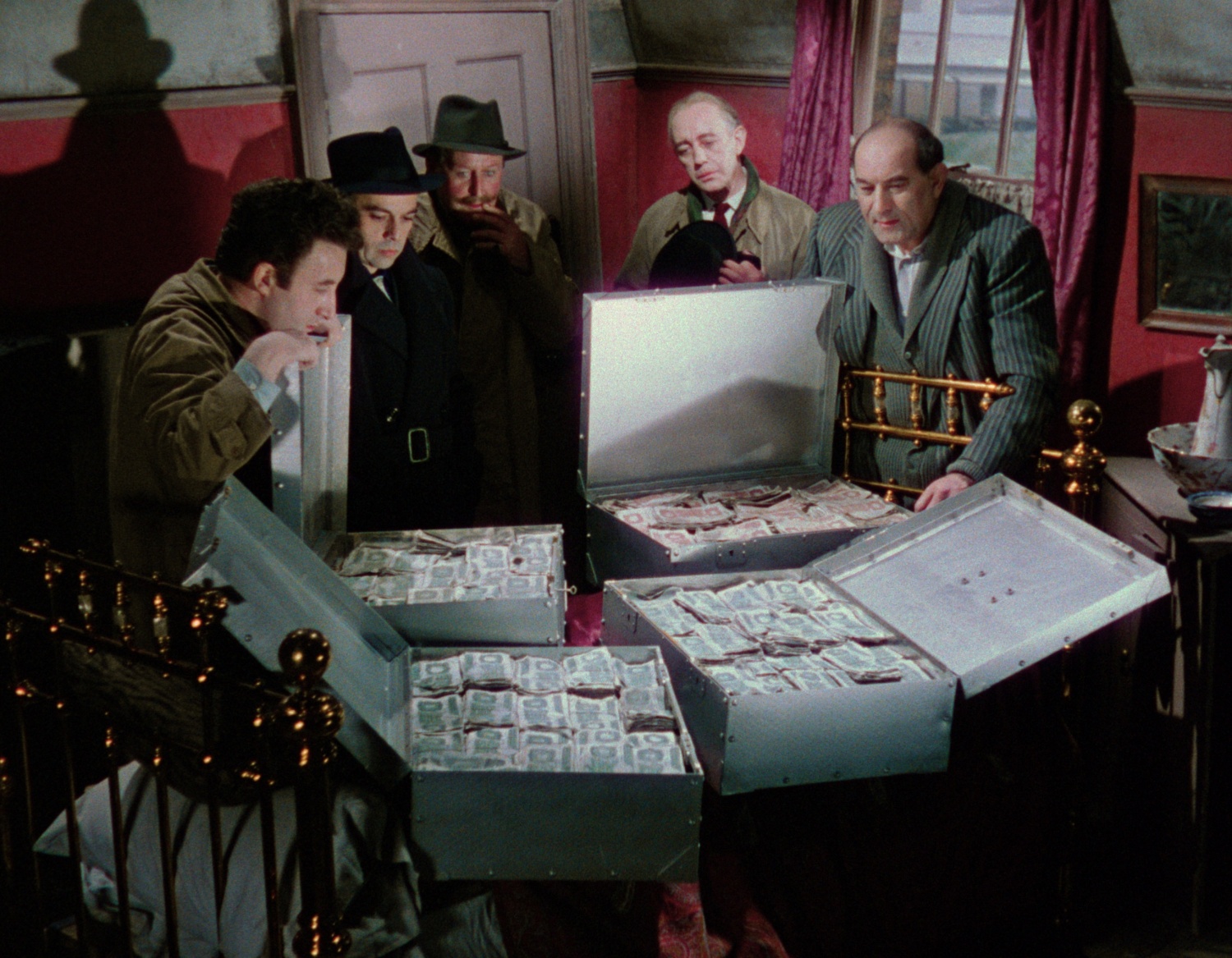

We are often compelled and gripped by salacious tales of crime and punishment, and there are very few criminals who are as charming and seductive as the anti-heroes of Patricia Highsmith's works. Although Highsmith was uneasy about the label of 'crime novelist', she weaves a world with twists and irrationality. Her works often seem to be more fascinated with delving into the disturbed minds of villains – gloomy and desperate, afraid to be left out hence hopelessly grabbing the love of attention and willing to do anything to avoid being nobodies.

In her famous Ripley novel series – which has been adapted into Purple Noon and The Talented Mr. Ripley, among others – the hero is a chameleon whose penchant for lying and murder are essentially extreme survival tactics. In Deep Water, a cuckolded husband's jealousy over his promiscuous wife turns him into a serial murderer; In The Cry of the Owl, a lonely man spies on a young woman and causes her fiancé to takes revenge; In Strangers on a Train, a wealthy psychopath concocts what he believes to be the foolproof murder: 'Criss-Cross' murders with a stranger in order to remove motivation from the act and thereby escaping suspicion. In her stark, uncompromising narrative where innocence and morality have no place, we may not necessarily sympathise with her criminals, but they often represent a debate over whether to fulfil our darkest desires, whether that be the desire to become someone else, to murder those we loath or to succumb to forbidden temptations. As Highsmith once wrote, 'every book is an argument with myself.'

Even The Price of Salt, which was adapted into Carol from Highsmith's sole purely romantic novel, was the result of her own desire for wish fulfilment: the story was inspired by her encounter with a beautiful blonde woman in a department store. Though the torrid love affair in the story was based on her other relationships, the author admitted that she had gone as far as following the stranger to her home. Seemed like Highsmith, too, used literature as an outlet for her own dark desires.

Back to the Screen

The Golden Age

Cinema Heritage: From The Film Foundation

Jonas Mekas: Remembrance of Things Past

A legendary figure of the American avant-garde, Jonas Mekas (1922-2019) was at [...]

Jonas Mekas: Remembrance of Things Past

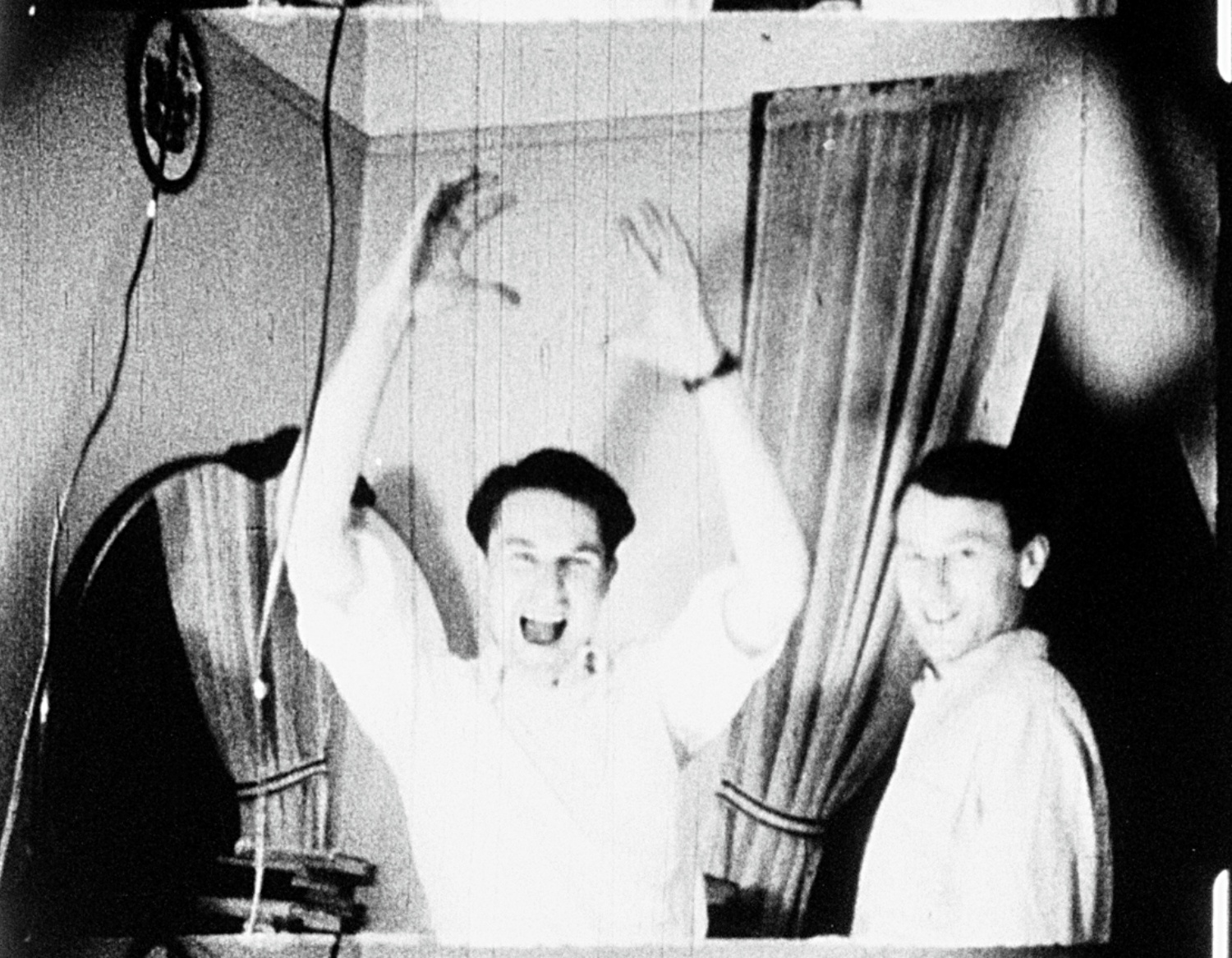

A legendary figure of the American avant-garde, Jonas Mekas (1922-2019) was at the heart of the Sixties underground film scene as a critic, curator, and filmmaker. Displaced from their native Lithuania as refugees in postwar New York, Mekas and his brother Adolfas soon joined the city's independent film community, founding Film Culture, Anthology Film Archives, and writing for the Village Voice. They advocated for a New American Cinema, forming The Film-Makers' Cooperative with figures like Lionel Rogosin and Shirley Clarke, and later focused on abstract works by experimental filmmakers like Stan Brakhage and Gregory Markopoulos.

Mekas turned towards avant-garde filmmaking and the diaristic form with intimate, personal epics, edited from 16mm footage of his daily life over the years. Mekas' was the art of the glimpse – life captured in the burst of a few frames – but also of memories recollected in tranquility: poetic fragments with narration or intertitles, accompanied by evocative music. The sense of wistful introspection derives as much from his lifelong feelings of exile as to how the company of others becomes a ghostly afterimage in the solitary act of remembrance, reminding us of Cocteau's eternal dictum that cinema is death at work. An advocate for 'oppositional cinema,' Mekas' challenging spirit against dominant culture codes keeps independent cinema alive and kicking in the age of digital globalisation.