2017

Centenary of Russian Revolution

In 1917, the Russian Revolution brought down the crumbling regime of the Tsar, envisioning a society built [...]

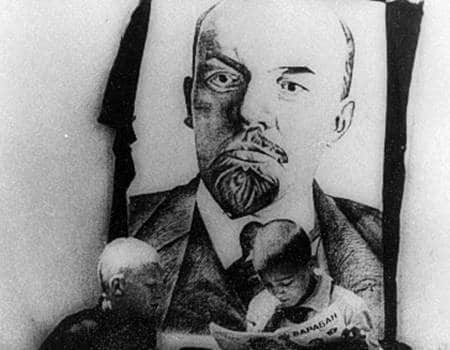

In 1917, the Russian Revolution brought down the crumbling regime of the Tsar, envisioning a society built around new men and women who would change the world. While this meant rebirth across the arts, by 1925, Lenin himself noted that “of all the arts the most important for us is the cinema.” The promises of these early revolutionaries seem dimmer after a century of politics and wars that have betrayed early ideals, but time has not diminished the ardor with which an early generation of Soviet filmmakers sought to explain and promote this new order.

Combining innovative techniques with powerful and political stories, these men made silent film an arm of the revolution, its vision, its voice. Indeed, they saw films not only as a way of showing the world but also of changing it, changing man himself. Who is not caught up today in the powerful images of power and corruption in Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925), a world-shattering reconstruction of a 1905 rebellion by sailors considered one of cinema’s great masterpieces? Where would we be without Dziga Vertov who revolutionized documentary with real everyday events and perceptions, a heritage that flows from his classic Man With a Movie Camera (1929) to contemporary cinema vérité?

While showcasing major works by both Vertov and Eisenstein, this panorama highlights works of their contemporaries who have never gained such currency among film buffs. This brings in works by Lev Kuleshov, founder of the Moscow Film School, who theorized and used montage so brilliantly that his name is still applied to a technique of evocative juxtaposition; he is seen here using satire as a political tool. He is joined by the epic Vsevolod Pudovkin and the comic Boris Barnet. Completing the panorama is another monumental film, Arsenal by Aleksandr Dovzhenko, a masterful voice from Ukrainian revolutionary cinema. Together, these brilliant works allow us to appreciate the filmmakers, goals and impacts of the days that shook the world.

The Biomechanical Dreamscapes of HR Giger

When that macabre unearthly creature came out in 1979, its creator, Swiss surrealistic artist H.R. Giger, has [...]

When that macabre unearthly creature came out in 1979, its creator, Swiss surrealistic artist H.R. Giger, has become internationally notorious as Alien. His visual style, which mixes gothic decay with serpentine futurism, has left a deep frightening impression on anyone who experienced it in the sci-fi classic.

Giger’s most famous book, Necronomicon, served as the visual inspiration for Ridley Scott’s classic thriller Alien (1979), which earned him the Oscar for the Best Achievement in Visual Effects for his designs of the “xenomorph” creature and the extraterrestrial environment. Compared to the great German expressionistic films such as The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) and Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922), Scott regards Giger’s work on Alien equaled on the sense of originality and vision. Much like the masterpieces of Hieronymus Bosch and Francis Bacon, the intensity of Giger’s art and imagination shares the same power to provoke and disturb, as it digs down into human psyches and touches our very deepest primal instincts and fears.

His high-profile film assignment can also be seen in many well-known thrillers including Poltergeist II (1986), Alien3 (1992), Species (1995) and Prometheus (2012), as well as the legendary unmade film, Alejandro Jodorowsky’s Dune. It’s a pity his lobster-claw-shaped Batmobile for Batman Forever (1995) never became reality, as it was replaced by a more conservative design.

Beyond the multimillion-dollar Hollywood franchises, Giger also has a powerful effect on visual culture in entirely different arenas. A director himself, he has produced a number of experimental films including The Second Celebration of the Four (1977) and Tagtraum (1973). He also rocked with avant-garde musicians like Debbie Harry and Dead Kennedys in album cover design and MV production, challenging the boundaries of creative freedom.

Passed away in 2014, Giger left behind a trail of images that linger in our mind like the never-dying Alien, with his artistic vision that will continue to inspire the wildest imagination.

“The Biomechanical Dreamscapes of HR Giger” is co-presented by

The Fight Goes On – Ken Loach

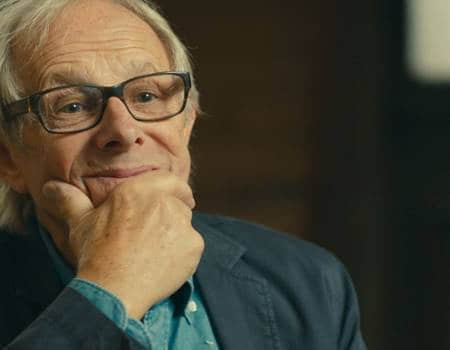

“If you’re not angry, what kind of person are you?” Britain’s most political filmmaker Ken Loach has [...]

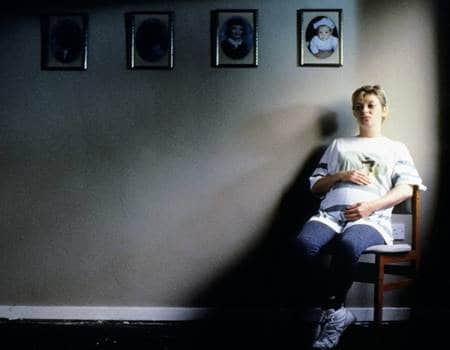

“If you’re not angry, what kind of person are you?” Britain’s most political filmmaker Ken Loach has spent the past half-century making films that shake with anger, venting out the frustration and humiliation to survival faced by the disenfranchised. Last year he made his angriest film yet, I, Daniel Blake , which won him his second Palme d’Or at Cannes. Still raging at age 80, his creativity is ignited from an abyss of darkness incarcerated by the ossified political system.

I, Daniel Blake is in many ways like Cathy Come Home, his seminal 1966 film which raised public awareness of homelessness and resulted in a parliamentary debate. Themes on exploitation, the indignity of unemployment, the resilience and humor of working-class people are constantly explored in his social-realistic docu-dramas such as Raining Stones (1993), Ladybird Ladybird (1994), which give the poor a voice against the bureaucracy. With his no-frills visual style and lean, sequential narratives, Loach is not out to impress anyone with techniques. Yet, his ability to capture the authenticity of experience and soul of ordinary people has made him both a skilful artist and a crusading social critic.

A thorn in the establishment’s eye, Loach has never yielded despite suffering from ban and censorship in the Thatcher era, even during the most difficult time when he, to his shame, had to make a commercial for McDonald’s. An extremely fertile period came after the “wilderness” days, as the director struck back with exceptional films including Land and Freedom (1995) and The Wind that Shakes the Barley (2006), which won him international acclaims including his first Cannes Palme d’Or and later, the Berlinale Honorary Golden Bear for his lifetime achievements.

An eternal fighter against social injustice, Loach, beyond doubt, will not go gently into that good night, and will continue to rage against the dying of the light.